We left Essaouira on a warm day. We passed argan trees and headed to wine country. We stopped at Domaine du Val d’Argan for a tasting. First we were introduced to their entire line of wines. It is today the only vineyard in Morocco to have obtained certification of conformity to European regulation CE 834/2007 which governs organic farming in Europe.

Then we were taken on a tour of the facility, which was like none that we had ever seen. The fermentation takes place in cement vats.

The aging then takes place in metal barrels.

They bottle and sell about 300,000 bottles a year, 90% within Morocco.

The owner of the place Charles Melia bought the original 12 acres in 1994 but now owns 129.

We passed the scraggly looking vineyards.

In addition to a tasting room and restaurant, they have accommodations of 5 overnight guest rooms.

We tasted 2 whites and 2 reds, which were not bad.

After the tasting we got back in the car for our long drive to the Ourika Valley. The final drive up to the hotel was on a narrow dirt road that winds up out of the valley into the High Atlas Mountains. We arrived in the late afternoon to Kasbah Bab Ourika.

As usual, the courtyard is lovely.

After a welcome drink we were shown to our room.

And once again, the bathroom is the best part.

As is the roomy private terrace with a view of the High Atlas Mountains.

We watched the sun set over the mountains then enjoyed dinner in the restaurant.

In the morning we were again struck with the beauty of the view from our terrace with the morning light on the mountains.

On our way to breakfast we noted how much later the olives ripen in the mountains than in the southern valleys. In Skoura they were already harvesting black olives. Here they are still not even yet ripe green ones.

After breakfast we met with our mountain guide Hassan. The dog from our hotel decided to join us on the hike.

Behind Eric and Hassan can be seen Jebel Toubkal Mountain. At 4,167 m (13,671 ft), it is the highest peak in Morocco, the Atlas Mountains, in fact in the Arab world. It is usually great for skiing, although no snow yet this year, which we are told is unusual..

After leaving the hotel property, we hiked around and almost immediately entered the Toubkal National Park. Hassan pointed out all the interesting flora along the way and explained each ones usefulness to the locals. Agave not only makes tequila, but the fibers are silk-like and are woven into fine cloths.

Juniper leaves are dried and smoked to help one stop smoking cigarettes. The wood from the juniper bush is burned and the ashes are dissolved into water and the dark liquid spread around the rims of food and beverage bowls to repel insects. The ashes can also be used in hair dyes.

The juniper berries make gin.

We passed honey bee hives.

At this point in the park we were able to look back and see or hotel in the distance.

We also passed a football (soccer) field built by the government for the children. It is here in the park due to the lack of ground in the villages, where all available space is used for homes or gardens..

We took a minute to stop and enjoy the beauty of our surroundings.

Hassan explained the danger of erosion of the hills due to storms. The government has been planting pine trees along the rims to help bind the ground.

We passed a wild oleander and Hassan reiterated its poisonous properties, especially if boiled.

Wild mint grows along the irrigation channels.

We hiked out of the park and passed along the top of a family farm on the border. The vegetables are sold at the Monday market.

As we came around to the front of the farm,

we saw a prickly pear cactus, a rarity here because they are all dying of a fungal infection. Hassan explained that the family can keep this single one alive by regularly cleaning it and covering it with the black soap we have seen in all the souks, which will prevent the fungus from sticking. The cactus berry is not only a delicious fruit, but the oil from its seed is used in anti wrinkle facial products.

On the edge of the farm was a carob tree. There was a time when the carob seeds were used to weigh the carats of gold, carat from the arabic word qurat which means unit of weight with reference to the elongated seed bod of the carob, hence the nomenclature.

This tree is just starting to bud.

Along the border of the farm are a line of agave plants. They are often used as natural fences to keep sheep and goats from wandering onto the fields.

He also pointed out that the agave will shoot up a flower after about 10 years or so, but then the plant dies.

There are chickens roaming near most homes. This one was just strutting, begging for her picture to be taken.

Hassan explained all the new construction seen everywhere. Most families all live together. As the sons grow and marry, they just add new homes onto the existing ones.

Some of the new homes use the old method of dirt, straw, etc. But most now use concrete bricks for immediacy.

Unlike in the city, which has community hammams, here almost every home has its own hammam often with an external access for the firewood.

The hammams account for the smoke we see from our terrace rising to the sky from many areas.

We passed the school with the children outside playing. They are off this week. About every 6 weeks they get a 1 week break.

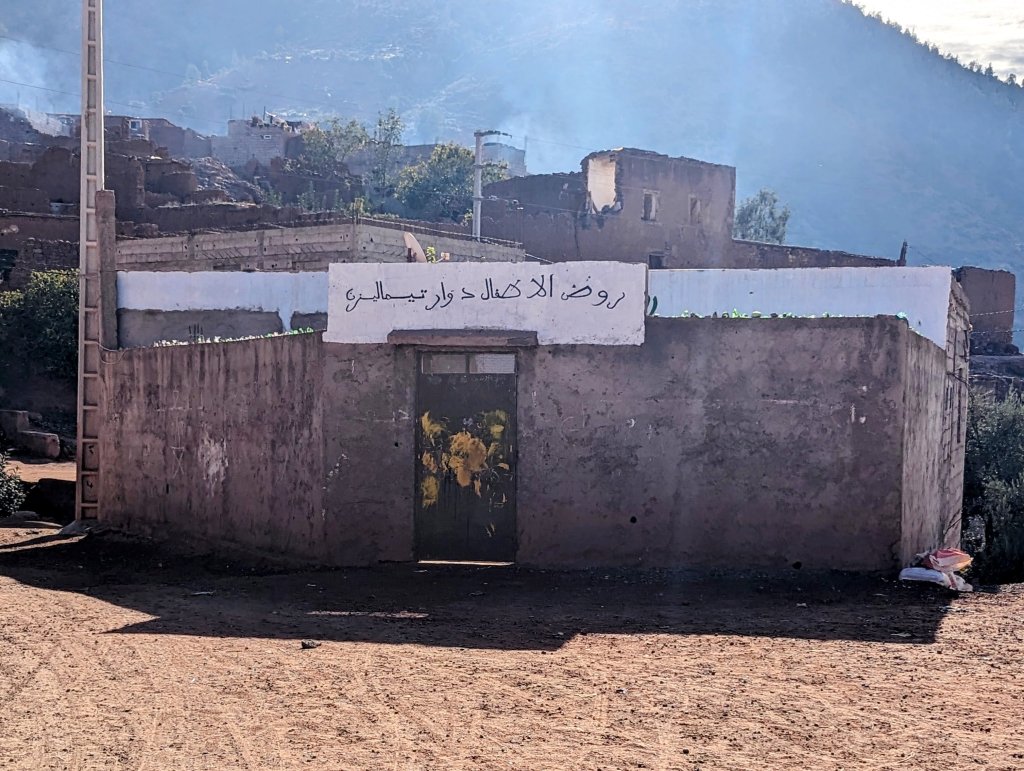

At this point Hassan, a previous science teacher, took a moment to lament the lack of funding for education and healthcare in the country. Since the 60s the population in Morocco has grown from 8 million to over 40 million. In that time, very few new schools have been built, yet many new soccer fields have been built. The students in the villages go to school in shifts, each child for only 3 hours a day. There can be as many as 50 students to a classroom. Where the teachers used to get a 2 hour lunch break, now they have a quick lunch break and work all day for no increase in pay. There is currently a teachers’ strike in Morocco. Across from the school is the kresh: preschool.

We asked about birthing babies. Most women have their first in a hospital because of the risk. But if no problems with the first, subsequent babies are born at home assisted by the village midwife.

Beside the school is the mosque.

As the government has brought running water to the homes, each home is charged for the use. In order to charge, the homes are numbered.

Before there were elected officials in each village, the villages were run by the wealthy chiefs who lived in kasbahs. This town’s abandoned kasbah was severely damaged by the Sept. 8 earthquake.

Walking through the village, we passed the local store.

This village also has an irrigation system, more sophisticated than the one we saw in the Skoura Valley.

There is a lever for changing the water’s direction, not stones and mud.

Hassan pointed out that the more luxurious looking homes we passed are all vacation homes for the more wealthy city dwellers from Marrakech.

One such fine home we passed was that of the owner of our hotel.

Very much like in the Skoura Valley, each family here has its own plots for farming. And similar to there, the plots are getting smaller with each new generation.

Hassan pointed out the many squash and pumpkin vines growing all around us. The large elongated squash, after taking out the marrow, used to be used as gourds for drinking and storing, but no more. Now it is simply cooked with Friday couscous.

The pumpkin vine is growing on the tree for support. The pumpkin is wrapped to prevent birds from poking holes into it.

Bitter oranges are grown for marmalade. Their skins can be used for orange dye. The blossoms are used for essences, scented products.

Sweet lemons are for juice but the bitter lemons are preserved for cooking in the tagines with olives.

He pointed out a quince tree.

A plum orchard

And an avocado tree.

The majority of the electricity is from solar panels.

We passed an abandoned wheat mill where the running water from the irrigation stream powered the wheel.

Alfalfa, feed for the animals, is grown in large fields.

There is a dog tied in the middle of the alfalfa field because his barking will scare away any wild boars that wander in from the park.

Sheep and a donkey graze nearby.

A Washington Palm is just for beauty; it bears no fruit. Have to wonder as to the significance in the naming of it…

Again, the irigation system is vast and impressive.

We passed fields of potatoes

and onions

The tomatoes are just about done for the season as the weather cools.

Finally we have arrived in the Amazigh family home. Amazigh is another name for Berber, which is what the tribes prefer. Berber was the name given to them by the Romans for “those who do not speak Latin.” Amazigh is the original for themselves in their native Berber language.

Stepping over the threshold, we are in the foyer of the home which contains the oven for baking the bread for guests.

There is a stable for the animals, which were out grazing during the day.

And a pen for the donkey, taking a mid day break.

This home, like most others in the village, has it’s own hammam, which I have come to understand is very much like a sauna.

The water is boiled over the fire, which is lit from the outside wall, then a little water is placed on the inside floor for steam. Inside the hammam one sits, relaxes, and scrubs oneself with the black soap.

Also in this foyer to the home is a room for the storage of food for the animals, mostly alflalfa both fresh and dried.

We then stepped through the door, past the bathroom facilities (all the homes in the village have running water and sewage lines), and into the inner courtyard.

Our lunch was cooking in the tagine atop the majamar.

Hassan showed us the kitchen with the everyday bread ovens that can also double to cook the large family Friday couscous.

He showed us the vessel into which they pour the milk, then swing it for about 30 minutes to separate the butter from the milk.

It is then simply hung on a peg for storage.

In addition to wood, butane is used for cooking. It is more expensive but more expedient to use.

The next room has the kitchen wares. We commented on the number of teapots!

And more cookware.

The rest of the rooms around the courtyard are for sleeping. We went up the steps to the level above. In the valley homes like this one have an open courtyard in the center. Hassan explained that up in the mountains, the courtyard would be closed and would be the stable for the animals, thus keeping the house warmer for the upstairs occupants.

And were invited into the guest room. Hassan explained that most Amazigh homes have a room used exclusively for entertaining guests. Here the extended family gathers to celebrate the end of Ramadan.

Hassan the proceeded to explain the ritual of making and serving tea. We realized that despite having been in the country for over a month, and having been served tea countless times, no-one had yet explained all the steps involved in the process.

He showed us the ingredients: loose green tea from China, lumps of sugar, and herbs, whatever you like, most often mint in Morocco.

First one must wash hands before the ingredients are handled, as well as before eating meals.

Then a handful of tea is poured into the teapot which is next filled with about a cup of boiling water. The water is swished to open the tea leaves, then poured out and saved. Meanwhile, choose what herbs, today he chose lemon verbena, sage, and absinthe, place them in a glass, and pour hot water over to cleanse; let sit a few minutes. A second cup of water is poured into the teapot and swirled vigorously to clean the now opened tea leaves. This dirty water is poured out and thrown away. Now the teapot is filled with water, the first rinse put back in the pot, and the rinsed herbs, their rinse water having been thrown away, are all added back to the pot, which is placed on charcoals and boiled a few minutes. If sugar is to be added, which it always is for Moroccans; (they physically work hard and burn the calories), the sugar is placed in a glass and the boiling water added to it to dissolve the sugar in the glass. The dissolved sugar is then added to the pot. A glass is poured out, then replaced into the pot a few times to ensure that the ingredients in the pot are all mixed well. Finally, a small amount is poured into a glass and tasted. If deemed ready, a half glass is poured for each guest. The first round is always a half glass for 2 reasons: if the guest does not like the herbs used, only a half glass is wasted and, the first round of tea is too hot to hold the glass. The half glass allows for room in the upper half of the glass for fingers to pick up the glass.

After tea, lunch was served. This is another Moroccan custom we have noted: tea is served first with nuts and cookies then lunch is served followed by fruits. The dessert seems to come before the meal.

After lunch we headed to the upper terrace for the views. In the distance another village can be seen on the hill. There are 49 villages in the Ourika Valley.

Also from above we can see the building going on next door. The family is adding a home for the eldest married brother.

There are more homes being built in the village also.

Also from up high we can see a row of poplar trees. Poplar trees are used for making furniture because of their flexibility. Their foliage is beautiful this time of year.

Down in the village we passed a home with a couple of large tents set up adjacent to the home. Hassan explained that means they are about to have a celebration. All celebrations are community wide events. Celebrations include weddings and circumcisions, the latter taking place after the baby is 40 days old but generally before 90.

As we left the village we passed several nurseries. One was for more poplars, another for cedar trees, also used for furniture and cabinetry. The trees will be transplanted around the area.

We then made the long hike up the hill back to our hotel. We had not noted prior but realized now, here also pines have been planted to stabilize the road from erosion.

We watched another sun set over the mountains, then another delicious dinner in the restaurant. The next day was one for more R&R. We took some time to enjoy the beautiful resort. While I shot photos on the ground including the lunch terrace

the pool

And the lending library/reading room

And the extensive gardens. They use rosemary as a border.

In addition to many olive, orange, and decorative trees, there are several rose gardens.

and many veggie and herb gardens.

Eric meanwhile sent up the drone to get views of the property from above. In this one the extense of the gardens can be appreciated.

This one particularly shows the gorges leading into the national park.

We spent a large portion of the day relaxing by the pool.

The next day we headed for our last stop: Marrakech. On the way we stopped at Le Paradis du Safran, an organic garden specializing in saffron. We had just missed the saffron harvest by a couple of weeks, but they had a couple of the flowers left to show us. The spice is derived from the stigma of the flower gently pulled off then dried. It takes a person 3 hours to collect the 200 flowers and remove theirs stigma to produce 1 gm of saffron, which is why it is the world’s most expensive spice.

The saffron field no longer had flowers, but the fields are expansive.

We wandered around the extensive gardens that had almost every fruit tree and herb imaginable.

One herb we did not know previously was this scented geranium, which has been included in teas and flavored waters we have been served while here.

The fruit trees also included ones we had not seen before like this kumquat tree.

And one we had never even heard of before called a pomelo.

When we had tea and snacks after touring the garden, we were actually served a pomelo which turned out to be much like a smaller, slightly sweeter grapefruit.

The grounds had pretty nice views of the High Atlas Mountains.

And some cute decor. These guys actually were triggered to play as we walked by.

They are also known for the “sensory garden.” We were encouraged to remove our shoes and walk through the different sensory stimuli. The peacocks and peahens took off before we walked through.

After the feet were stimulated, there was a series of baths, salts, rinses, and finally scented herbs to rub onto the feet before snacks were served.

We then drove up to the red city: Marrakech. As per the usual mo, we were met just outside the medina by a porter from the hotel. I realize, I have never included a pic of the little hand trucks the porters use to transport luggage through the streets of the medinas. Not all are a decorated as this one.

We were greeted at L’Hotel Marrakech, which is really a riad with its innocuous door.

The turn into the narrow entryway.

And the beautiful central garden.

We were shown up to our private terrace overlooking this courtyard.

And into our room styled in the 1930s French motif.

After we settled in, we wandered back out into the medina for Eric’s badly overdue haircut.

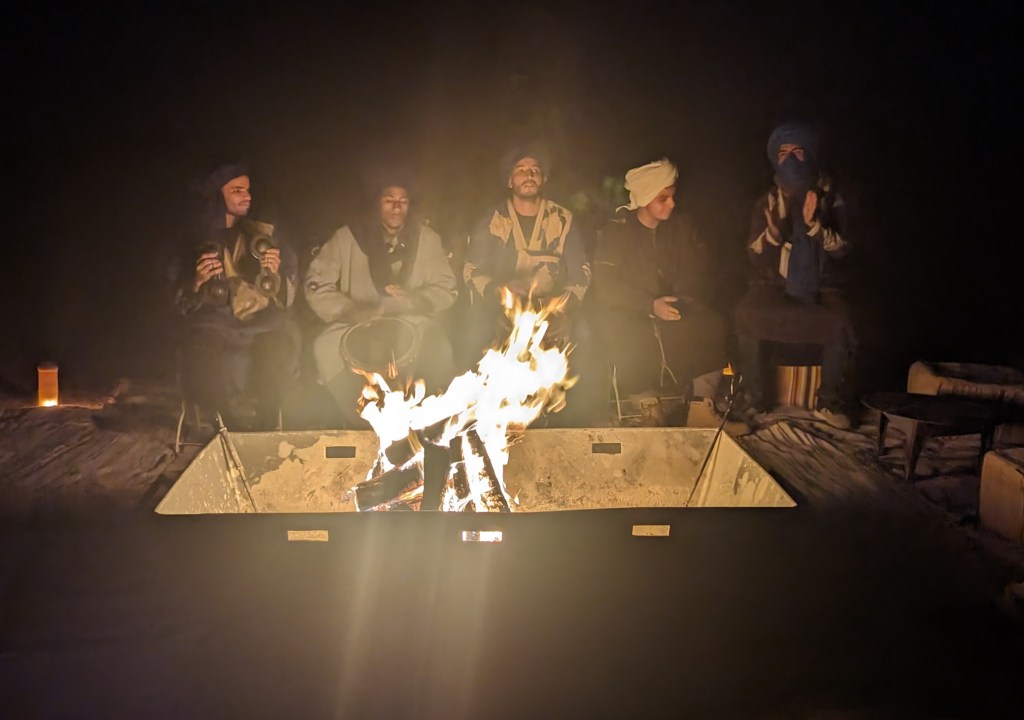

We had a lovely dinner by the fire in private in the dining room. I have probably not mentioned before, but this is the best time to be in Morocco. The weather is still gorgeous, and the tourism is at a low. In several of our accommodations, this one included, we have been the only guest for 1 or more days of our stay, such personal attention and privacy, luxurious.

After breakfast (included in every place we have stayed) Mohammed, our guide for the day, met us at the riad. Having been in the country at this point for over a month, we challenged him to find information and food we had not yet experienced. He rose to the challenge and succeeded on both counts!

First he took us out into the street of our neighborhood and explained that the larger medinas, like in this city, are divided into neighborhoods called derbs. The derbs are mostly residential, although now a lot of homes are being converted into riads and spas. Each derb has its own prayer hall for the daily prayers, but is not a mosque and does not have Friday prayers.

We are in derb Sidi Lhassen ou Ali. Sidi is a special title for a male, like “lord,” Lala for a female. Lhassen ou means “son of” like ben in Hebrew.

Many derbs also have shrines to saints that previously lived there.

Mohammed also explained that as plumbing was introduced into the medina, the pipes were laid, then the road built up over, which is why many doors and homes are now significantly lower than the street.

The houses are numbered from right to left, as Arabic is written. Shrines, prayer halls, and mosques are not numbered. He also explained why so many of the doors seem to have a smaller door within a larger frame. The smaller door is for people, the larger was to allow for the animals to enter. Nowadays most people in the medina do not keep large animals in their homes, (they have motorbikes) but keep the old doors because the smaller doors are cooler.

As families grew, if extra space was needed, the house could be built right over the alley.

Several derbs open into a larger space that is the center of the neighborhood of the medina. As explained previously, each neighborhood had its own mosque, hammam, bakery, water supply, and madrassa. Our neighborhood mosque with the accompanying water fountain have been converted into a museum.

The central area onto which all the derbs open is the area for shops and services like mechanics, tailors, electronics, food

and barbers

And nowadays, a laundromat

Our neighborhood 16th century madrassa now is also the local public school.

The neighborhood bakeries were once public. They are all now private businesses that charge a nominal fee if used by a private person. But mostly they bake enormous quantities of bread for the hotels.

This is the current neighborhood mosque.

The latrines were also once all public and centrally located.

This one is now in disrepair, but has the original area for washing clothes.

The toilets can be used for about 1 dirham (10 cents).

a close-up of the squat toilet. I only had to use one once in the month we’ve been here. No toilet paper but fortunately I had my own.

Then water is provided for washing after using the toilet.

The medinas are all undergoing restoration, which involves sealing and painting over the new cement bricks of the new buildings while keeping the original color for which the city is known..

Originally the groves and gardens that fed the city were immediately outside the medina walls. Today there are only token gardens in the urban sprawl that is Marrakech.

The hammam, still in use, can often be recognized because it has a large central dome under which people sit while in the sauna, for purification.

Recycling is huge here. Almost everything is recycled. While walking through our derb, we heard a man calling (in Arabic) for bread. He buys partially used or stale loaves and sells them to farmers as feed for animals. This donkey is pulling a recycling cart through the medina.

The next neighborhood we passed through was Laksour (palaces).

which is one of the oldest near the famous mosque: Koutoubia, which means book sellers. We got our first glimpse of the famous mosque.

As we neared, we could see the 12th century mosque and the nearby shrine.

Because of the Sept. 8 earthquake, the mosque is considered unstable and cannot be entered, which is why it is surrounded by barriers and the side and top are supported.

Originally in the space was an 11th century mosque, which was mostly destroyed but not removed; the ruins remain.

The Koutoubia Mosque was built in the Moorish/Andalusian style about the same time, by the same dynasty, as those in Sevilla and Rabat. They were based on the one in Cordoba (and the 11th century one which they destroyed). The columns are aligned to face the mihrab (prayer niche), which is facing mecca.

Beneath the old mosque is a large water cistern.

It is filled by water from the High Atlas mountains that comes through a system of channels.

The new mosque reservoirs are considered so special, they are considered a spiritual place and are named for special people.

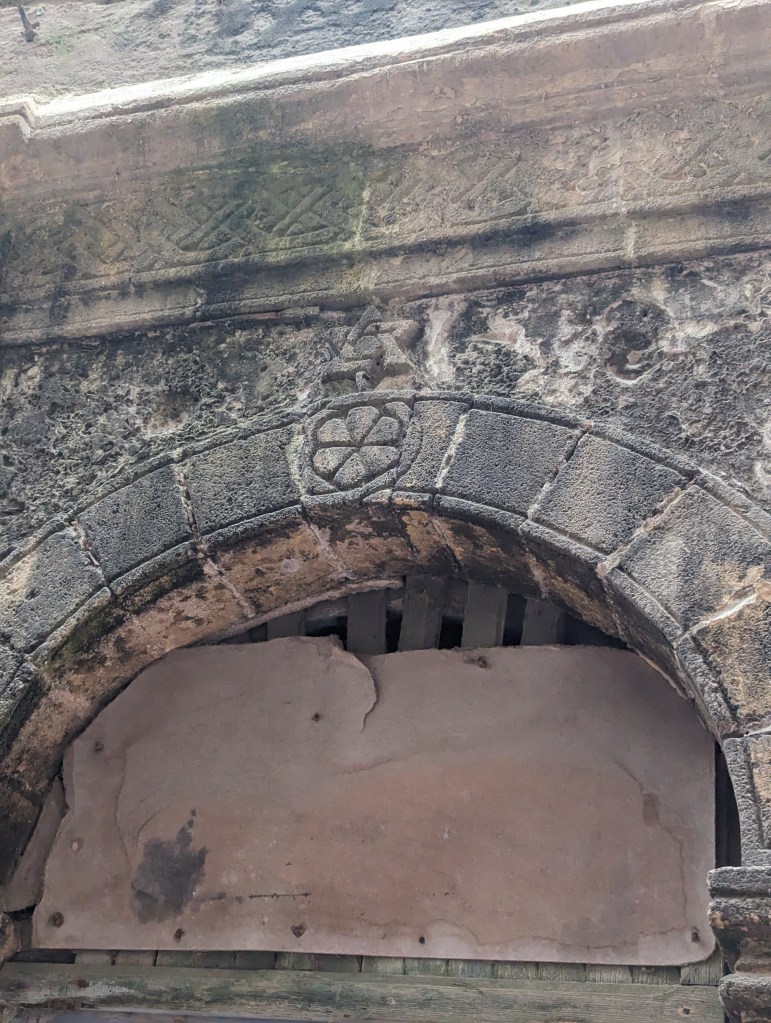

Mohammed explained that the typical Muslim door style, the keyhole, with the upper horseshoe shape, dates back to the Romans who considered horseshoes to be good luck.

Like all mosques, there is a large public space adjacent, in this case a park.

The central round fountain, however, is more of a European, ie French, influence. The typical muslim garden is square, in 4 symmetrical quadrants.

Stork nests can be seen in the nearby cellphone towers.

Heading back toward the mosque

Mohammed pointed out the woman dressed all in white. He explained that she is in mourning. In a very strict family, she would not come out, unless in an emergency, for the duration of the mourning period, which is 4 months and 10 days. (If the death is a husband, in that time a pregnancy would be known.)

As we walked around the mosque, Mohammed explained that the minaret internally has ramps so a donkey could carry a man to the top to call for prayers. The external niches provided amplification of the sound in the days before electronic loudspeakers.

The braces around the minaret are to hold it together due to earthquake damage.

The post earthquake damage was dealt with quickly in Marrakech. The buildings across from the mosque have supports due to fears of crumbling, especially in the immediate post quake aftershocks. Marrakech is considered the “Image of Morocco,” so it was important that businesses reopen rapidly.

We left the mosque and crossed a huge busy intersection.

In the middle island is an old French canon.

Across the intersection is the road that leads to the Jemaa el-Fnaa, the largest, most important square in the Marrakech medina. At the entrance to the road is the horse carriage parking spot.

The horses are Bard horses, which are a cross between the Arabian and Andalusian breeds.

As we entered Jemaa el-Fnaa, we took a look back at the Koutoubia Mosque.

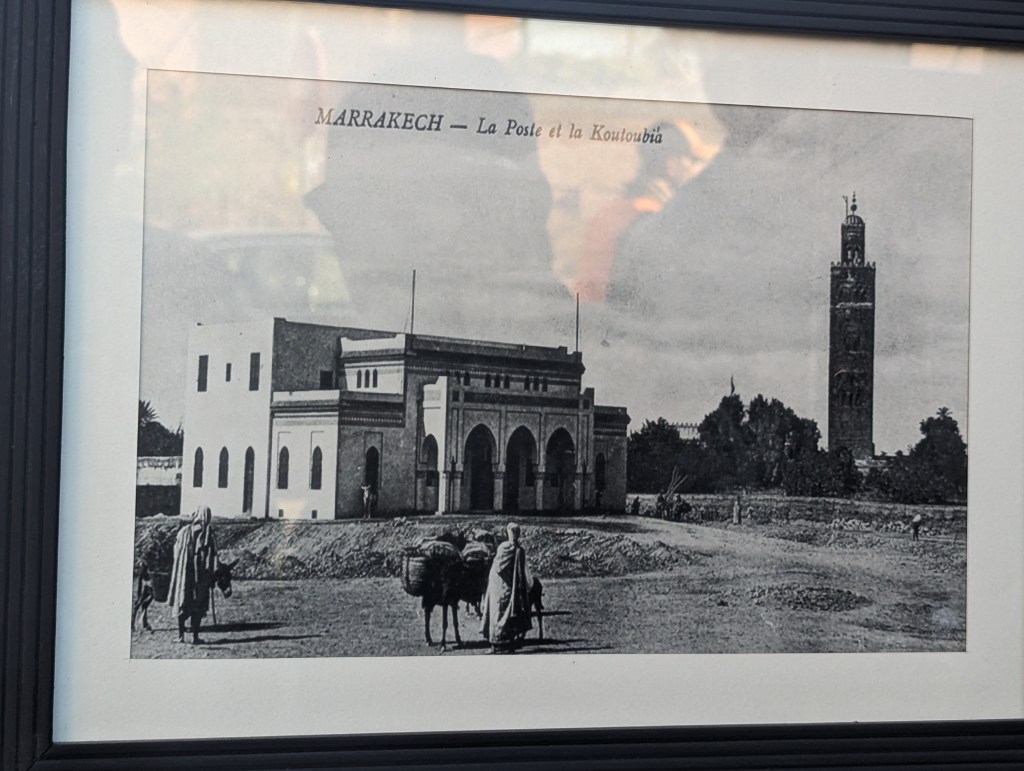

At the front of Jemaa el-Fnaa is the post office, still in use, and what was a bank, now a museum.

Mohammed had shown us a picture taken in the 1910s of this same location.

Jemaa el-Fnaa has been declared by UNESCO as a world heritage site due to the unique culture found here.

A lot of which can be explained in the museum. So before exploring the square, we decided to go into the museum inside the bank, already completely restored from the earthquake damage.

The inside space has the feel of an old bank.

Because Marrakech is well protected by the surrounding High Atlas Mountains, it was the central location for trade on the caravan trails between the ports, and their salt and goods from Europe, and from the East: gold, silver, rugs, produce. Jemaa el-Fnaa was the social center of Marrakech. In it could be found storytellers: Halqa.

Storytelling has always been an important tradition in Jemaa el-Fnaa, so much so that it has become a focus in theater and subsequently movies. There is an entire room in the museum featuring movies with scenes either made in or based on Jemaa el-Fnaa.

Other performers who frequented Jemaa el-Fnaa included the snake charmer.

And many musicians playing gnoua on the drum, the qaraba (castanets) and the guembri, the 3 string guitar.

The display below shows peoples who would have frequented Jemaa el-Fnaa including the seated scribe and the typically dressed tribal folks.

We then went back to the square.

Outside in the square we immediately found a snake charmer.

There were also several men with monkeys on chain leashes. Animal rights activists are vocal against both of these animal abuses, but UNESCO protects them because they are part of the heritage. I did not want to give a monkey trainer money for a picture, so none included. We made our way through more streets filled with shops in the medina. A favorite shop was this one full of instruments.

Then Mohammed made good on his second challenge. He found us food we had not yet tried: mechoui. any vegetarians, be warned. The following is for serious carnivores only. Mechoui is is an entire young lamb roasted is an oven in the ground.

We ordered up 2 kg of lamb, bread, mixed spiced olives, french fries, and a couple of cokes, and lunch was served. We figured we had been in the country over a month and neither of us had gotten travelers’ sickness, so time to live daringly. Once our portion was chopped up, it was placed in a bucket and lowered back into the hole to be warmed.

While we were eating, he pulled out a whole lamb, and we were able to see how it is roasted tied to a stick. It is eaten with salt mixed with cumin, as seen on the table, so juicy and delicious. After lunch Mohammed walked us down an entire lane of street food representing choices from all over Africa and the Middle East.

One note, a very annoying aspect of walking around the medina in Marrakech is the large number of motorcycles that come racing by often dangerously.

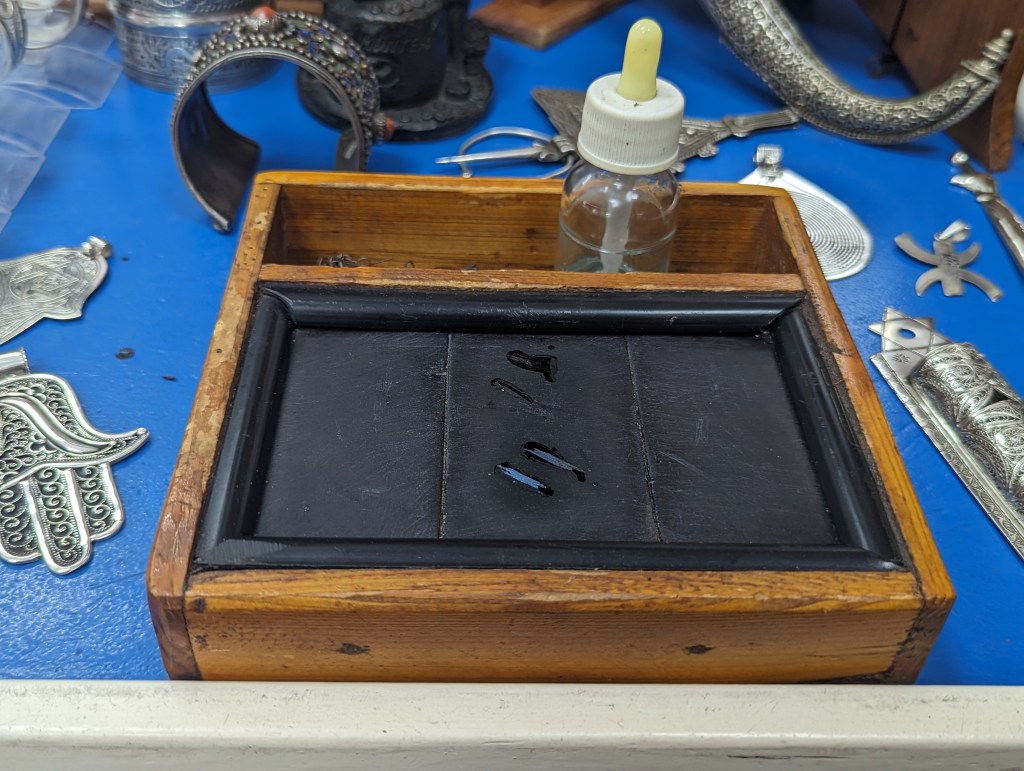

We then headed to the section with the souks and souikas, which is the diminutive meaning small souk. Traditionally, the souk is where the artisans are actually making the products. Usually the artisans do not sell their own products, but sell them to merchants who then sell them in kissarias, which are galleries that display the objects made by the artisans. Today they are a bit mixed up. But there are still some souks for specific crafts like straw weaving

and dying wool and silk

all the possible wool colors

all the silk colors

scarves come in all the colors of the sahara

today’s color is red. The dyed wool is hanging outside drying.

The pigments for the dyes can be bought, as well as the dyed wool, usually from the same stall as spices.

And near the souks can be found shops that hold the tools necessitated by those artisans like this one for tailors’ supplies

In places, several souks will open into a square like this very colorful one.

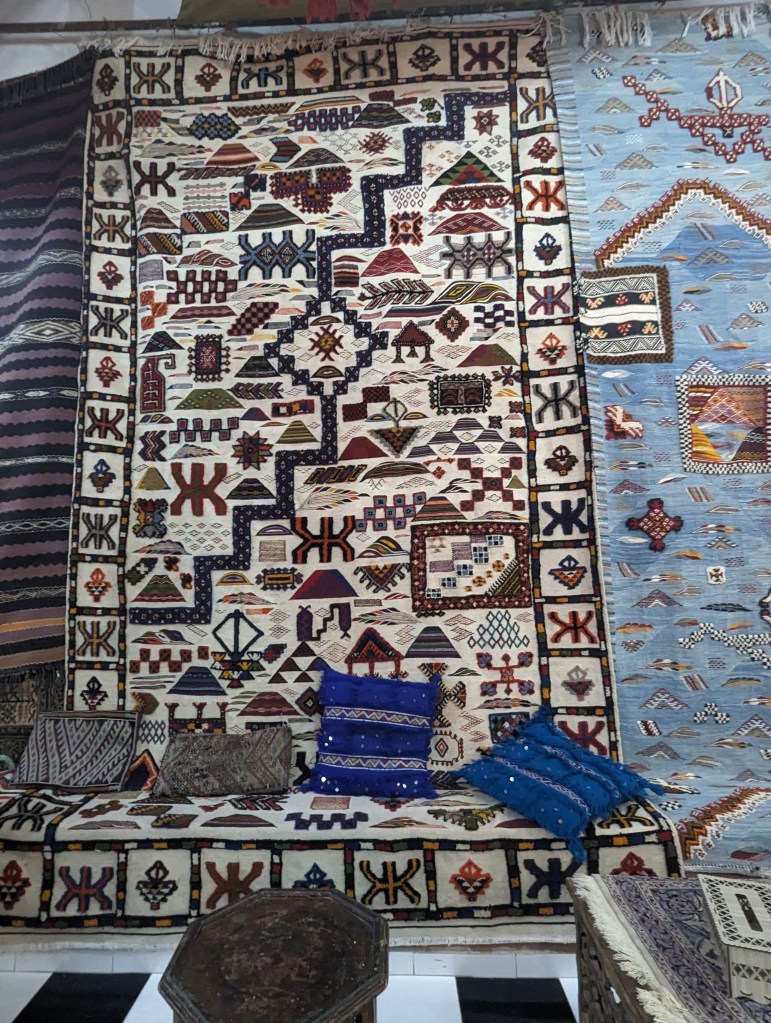

This rug marketplace has stalls with all new rugs, some specializing in rugs from certain regions, and some stalls buy and sell used rugs.

There is an entire metal souk

The souk haddadine is all metal works with sparks flying. Some items being made are utilitarian, but this man is an artist.

This man is soldering pieces together.

And this one is a locksmith for locks large and small.

In the leather souk we saw artisans doing everything with leather imaginable: dying, cutting, gluing, and sewing.

This man is cutting soles for making shoes.

We were introduced to man bags. Because most men wear djellabas, they do not have pockets. So they carry a bag over their shoulder.

This artisan specializes in saddles.

For the leather souk there is not only a parts supply store,

there is also a nearby knife sharpener. The wheel he uses is made of sandstone and will be used until it is mud, then he will get a new wheel.

This is the leather kisseria, with the typical high wood ceiling to protect the goods.

As we walked around we went down a street that has been braced since the earthquake.

And also this minaret, tied around because of the large crack right up the middle.

In this neighborhood, there is also a mosque and school with accompanied madrassa. It also had a museum, but we were not in the mood for another museum. We felt like the souks and kisserias are enough like living museums.

As described in Essaouira, fondouks were historically where camels were brought with their wares and were mini self contained markets. Because Marrakech was the largest trading sight, there were many such fondouks. Mohammed showed us a picture of one from 1910.

Today they are being renovated and are boutique shops or coops. We saw several.

They are often named for people or places if not the types of wares they sell. The one below still has the original scales.

As we got closer to the big hotels, the shops and boutiques became more upscale and more expensive, as seen in the fondouks above. Mohammed explained that this area with the nicer, bigger hotels was called the hivernage district which means wintering in French. During the French protectorate period, they would come to Marrakech during the winter months but spend the hot summer ones either in the mountains or near the seaside. While walking, Mohammed gave us a brief recap of the French/Moroccan history. As stated previously, in the early part of the 20th century, the French decided that Morocco needed protection not only from warring European nations, but also internally from the warring tribes. But really they were using Morocco for its resources. They built the railway systems and roadways to enhance the trade routes. They put no money into the medinas or infrastructure for the small villages. When they left in the 1950s, Morocco was left a bit destitute. Marrakech was a very poor city for a couple of decades. It was the hippies and the “discovery” of the “Marrakech Express” that put the city back on the map with an influx of tourists and with them money.

We left this neighborhood to head back to ours. Along the way we passed a palace, not of the king but of his family, called Darel Basha.

We asked Mohammed about the uniforms of the different military posted out front. At every entrance of every palace there are guards, usually several. He said each represents a different branch: the red is the army, the camo the equivalent to the marines, the grey are non weapon carrying somewhat like the national guard, etc. He says at least one from each of the branches are required to protect the palace for national security because each has a different chain of command. There is also a navy and an airforce, neither of which are represented here.

That evening, having already dared the street food, we went back out and dared it again, but this time with Middle Eastern fare: falafels, shawarma, and hummus.

The next day we spent the morning and early afternoon back in the medina, wandering and shopping for presents to take home. Later in the afternoon we headed to a hammam/spa. We had been in the country for over a month and had yet to try a hammam. Kamal had insisted that we go at least once. For obvious reason, I have no pictures. But I will describe the experience in detail because it was like no other. Public hammams have men and women separated. But in this tourist hammam, since we booked together, we had a couples’ experience. After tea and flavored water to prehydrate us, we were taken to the changing robes. They discouraged bathing suits because they are too difficult to work around. Eric’s was paper briefs. I was given a paper thong that covered very little, nothing for the top. We had robes and slippers until we got into the hammam. Then we lay first face down on a wet heated mat. The washers are all women. We were each scrubbed thoroughly top to bottom, front and back, (every inch for me, Eric briefs area excluded), with the black soap which is made from olive oil base. The washers left for a time, and we then lay there quietly for a bit. Then they returned and using a loofah-like mit, they scrubbed us hard going over every area several times, exfoliating every cell of dead skin and then another layer, or so it seemed. It bordered on painful in spots. Then, using warm water, we were hosed down in a standing position. We were then told to lay down again and were covered in a red clay. Again we rested supine for a bit. When they returned this time, after hosing us down, they scrubbed us with a more foamy soap, shampooed our hair, then hosed us down completely. The whole process took about 45 minutes. We were then wrapped back into our robes with towels around our heads and led into a room with cushions on the floor and again served tea and flavored water, this time plus some cookies. After resting here for a bit, it was time for massages, which Eric had opted out of. My massage was pleasant with just the right amount of pressure for me. It was also the most complete massage I have ever experienced (I have never had my breasts included before). I particularly enjoyed the scalp massage.

After, Eric met me we walked back to Jemaa el-Fnaa. We had been told by both Kamal and Mohammed that the best time to go is early evening when it is packed with street performers. This being a Monday night off season, it was not as busy as we expected. But there were dancers, musicians, and acrobats in addition to the snake charmers and monkey trainers. The street leading into the square from the big hotel area was teeming with people.

And we were able to watch the sun setting behind the Koutoubia Mosque.

We then crossed the square and climbed the stairs for a rooftop dinner at Le Grand Bazar.

In the morning Kamal drove us to the Majorelle Garden and the attached Yves Saint-Laurent Museum. From their website:

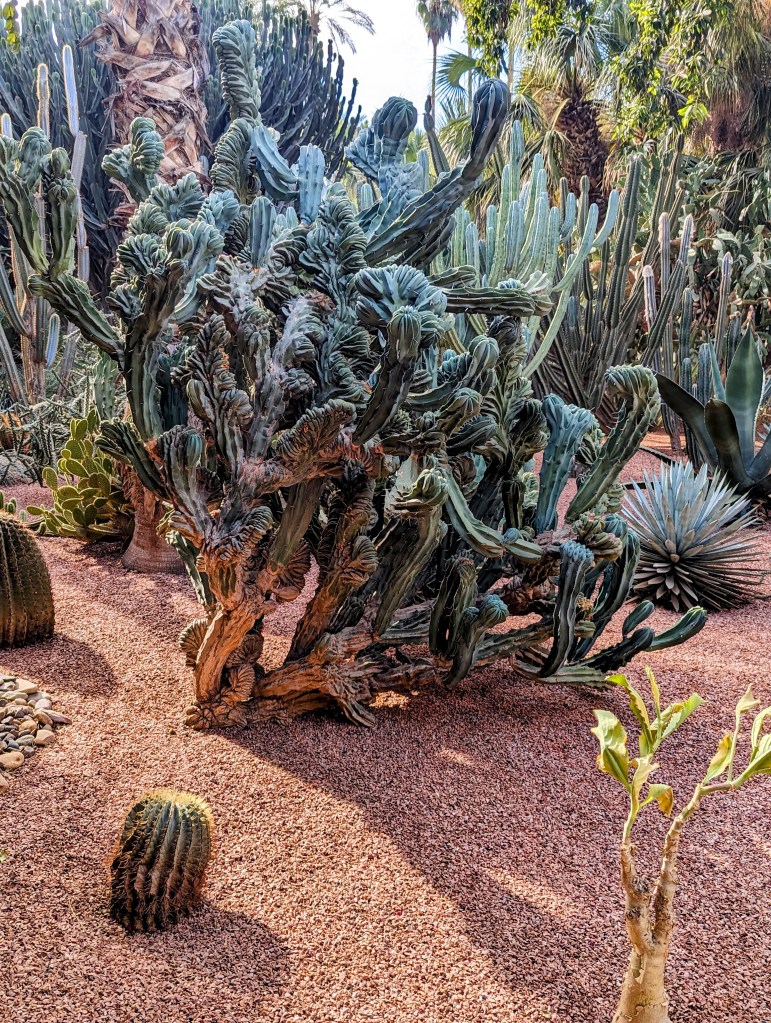

The Jardin Majorelle, which extends over 9,000 m², is one of the most enchanting and mysterious gardens in Morocco. Created over the course of forty years, it is enclosed by outer walls, and consists of a labyrinth of crisscrossing alleyways on different levels and boldly-coloured buildings that blend both Art Deco and Moorish influences. The French painter Jacques Majorelle conceived of this large and luxuriant garden as a sanctuary and botanical ‘laboratory’. In 1922, he began planting it with exotic botanical specimens from the far corners of the world.

In 1980, Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé, who first arrived in Morocco in 1966, purchased the Jardin Majorelle to save it from destruction at the hands of hotel developers. The new owners decided to live in Jacques Majorelle’s villa, which they renamed the Villa Oasis.

Upon entering the gardens we were immediately struck with the beauty of the many varieties of cactus, most of which were imported from Mexico and South America.

But what also stands out are the colors, specifically the Majorelle Blue, so named because of its use in this garden. Majorelle had noticed the colour in Moroccan tiles, in Berber burnhouses, and around the windows of buildings such as kasbahs, and native adobe homes. In Morocco it is known as the color of the sahara.

There is a koi pond.

and a memorial to the man YSL who passed away from brain cancer in 2008.

The garden has the tallest bamboo we have ever seen, and we saw a lot in SE Asia.

There are fountains throughout.

There were also a couple of cactus species that were unusual; neither of us had seen before.

There is a little building in which there is a shop supporting local artisans. It also has a room dedicated to all the “love” postcards that YSL designed yearly and sent to friends and family.

There is also a Berber Museum. From their website:

The Berber Museum, inaugurated in 2011 under the High Patronage of His Majesty Mohammed VI, King of Morocco, is housed in the former painting studio of the artist Jacques Majorelle. It presents a panorama of the extraordinary creativity of the Berbers (Imazghen), the most ancient people of North Africa. More than 600 objects, collected from the Rif Mountains to the Sahara by Pierre Bergé and Yves Saint Laurent, attest to the richness and diversity of this vibrant culture, which is still very much alive today.

Pictures were not allowed inside the museum. There were artifacts, jewelry, and clothing of Berber tribes from throughout Morocco. We did not learn a whole lot more than we had visiting the villages throughout our trip. But it did make us feel grateful that we had truly visited all of the different cultures and learned so much during our journey.

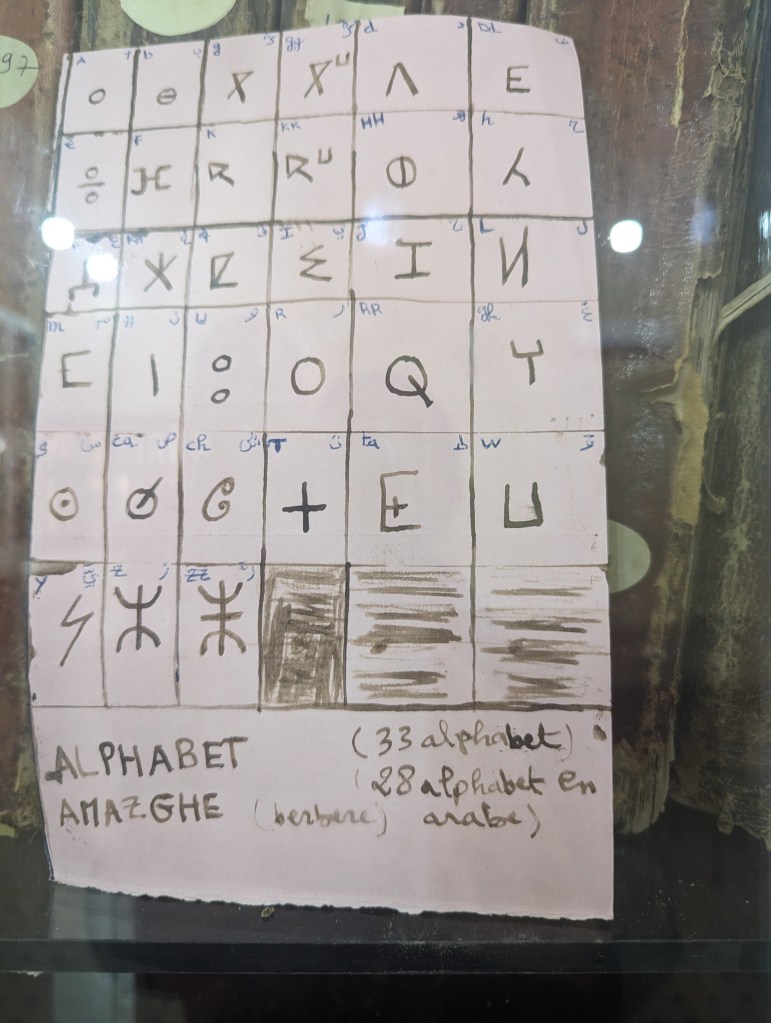

The 2 pieces of trivia we did pick up, somehow missed prior, is that the Berber language is called tifinagh. I had previously taken a picture of the alphabet and will include it here

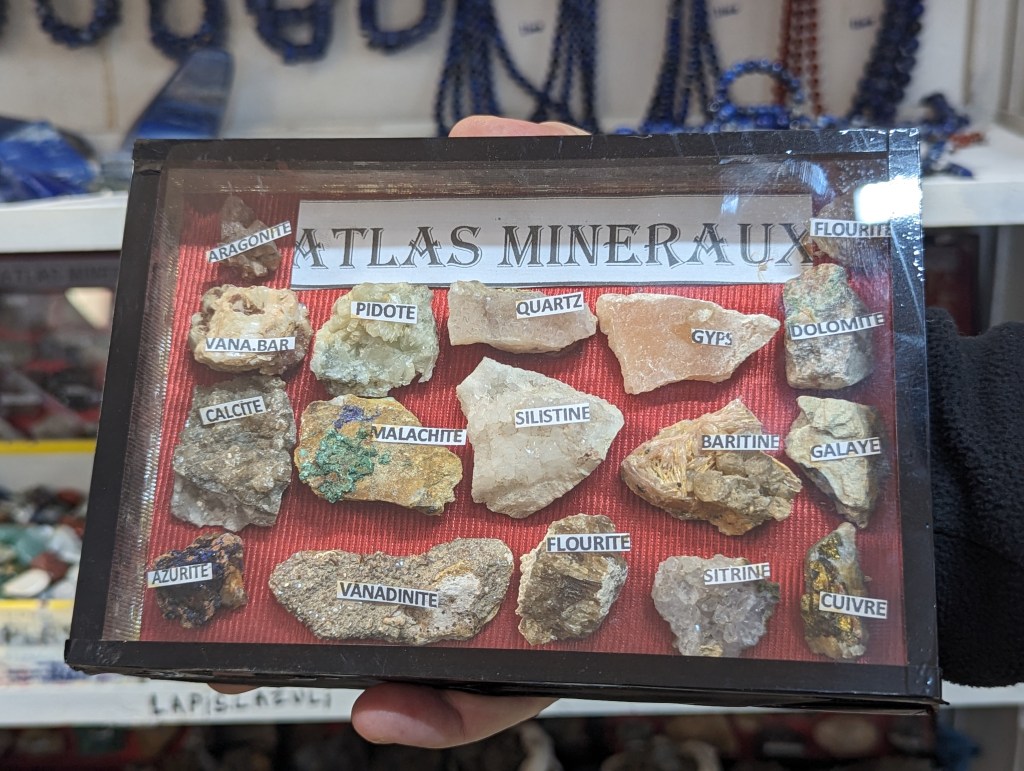

The other piece of information we picked up in the museum is about one of the symbols we had been seeing everywhere which looks like this

The specifics vary from tribe to tribe, but it is a triangle with the circle with a pin through it above. It classically was worn by a woman in a Southern tribe as a brooch to clasp her melhfa. If she wears one, she is single, two for married. The symbol itself is derived from a pagan one and is symbol of protection a little like the hand of God symbol used by all 3 Western religions.

We finished the Majorelle garden tour.

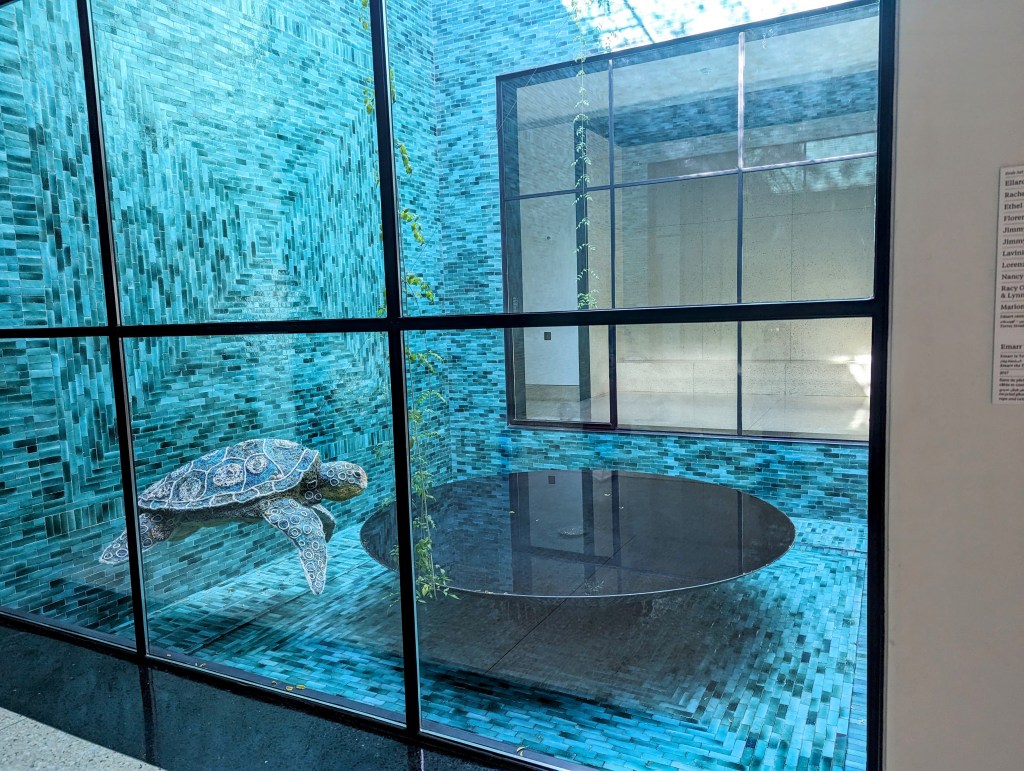

And headed to the YSL Museum. There pictures were forbidden again. The museum had a lot of line sketches made by YSL through the years and lots of his haute couture prototypes made through his decades of designing. The garments are each like a true work of art. There was also a little theater with a short documentary about his life and career and showed a video of his retrospective show at the time of his retirement in 2002. The only picture allowed was that of the central courtyard. The turtle is a suspended statue.

After the museum we took Kamal out for a thank you lunch. As we drove there we passed the large hospital/university complex of Marrakech where he has been taking his mother every 4 months for chemo for her breast cancer. We asked him about the health system in Morocco. A toubib is a healer. His explanation sounds very similar to ours in the US: the very poor have a public system that is free but overcrowded, understaffed, long wait times, and often inaccessible. Those that can afford can buy private insurance. But he has to drive 8 hours for the nearest cancer center. He has to pay for rooms for him and his mother for the several days they need to be in town for her treatments. And the out-of-pockets costs for the medical care are still significant. Dental is never covered and is very expensive.

For our lunch Kamal chose the Amal Women’s Training Center Restaurant with the mission ”to provide a safe and loving space where strong, resilient women can rewrite their narratives and step into their power.” It trains underprivileged women to be chefs. The restaurant food is cooked by the students.

I particularly loved the quote on the wall.

Kamal is a beautiful person who made our trip through Morocco a beautiful experience.

After lunch he took us on a driving tour through the new sections of Marrakech with the golf courses, large hotels and resorts. Businesses included everything from McDonalds and Starbucks to Saint Laurent and other boutique shops, Moroccan as well as international. The avenues are wide and palm lined looking a little like Miami but with the High Atlas Mountains as the backdrop. He then took us back to the riad for the last time. In the morning we were to leave Morocco and start our journey back to NY. Our 15+ weeks of travel was nearing the end.