Today we were in for a long car ride to the edge of the Sahara Desert. Leaving Ifrane there were Barbary apes along the side of the road.

We drove through Midelt, the apple capital of Morocco with a green apple statue on one end of town, a red one on the other. Unfortunately due to the drought, the trees were sad looking.

The we passed the Ziz Gorge and got our first glimpse of date trees.

Dates grow in large bunches.

The gorge was spectacular.

The valley is extremely fertile. The locals build homes in villages using the plentiful clay. Their villages blend right into the landscape.

We met Tata, who will be our guide in the Sahara for the next couple of days, at his parents’ home. His family has lived in Ziz for over 300 years. He explained that a family can build as many homes on their property as they have room for. Dates are the main source of income for the locals, and the only produce exported. The villagers farm in cooperatives for their own consumption. He showed us fava beans:

alfalfa:

carrots and turnips:

He and his son showed us many of the 40 varieties of dates grown here in Ziz Valley, home to over 3 million date trees.

Tata also lamented that their date industry has 3 threats: drought, desertification,

and a blight that has recently moved in.

We were then treated to snacks, of course with dates, in his home garden surrounded by fig trees, grape vines, and herbs.

We then made our final leg of the day to Erfoud, which has a date festival every October. Our hotel for the night was La Rose du Desert.

We had tea and snacks by the swimming pool.

Dinner was an abundance of Moroccan salads and chicken tagine with preserved lemon. Then it was time to rearrange our clothes to take just backpacks into the desert.

In the morning, before leaving Erfoud, the fossil capital of Morocco, we visited the fossil museum and shop. There is a quarry about 25 km south of Erfoud from which fossils and minerals are extracted.

Our tour started with an explanation that the theory is that all of the land was initially one giant land mass. This entire area was under a sea until about 225 million years ago.

The fossils found in this area include: orthoceras, an ancient mollusk that lived more than 350 million years ago. It had a shell with separate compartments which could be used as a ballast.

And ammonites which are cephalopods that lived in the jurassic and cretaceous periods 140-250 million years ago.

And crinoīdes, an echinoderm commonly known as sea lilies or feather stars.

And stromatolites which created by a bacteria that is microscopic and the first organism to be able to carry out photosynthesis.

And finally, trilobites, which are one of the most important early animals studied; they were the fist to have eyes.

There are also starfish found in this quarry.

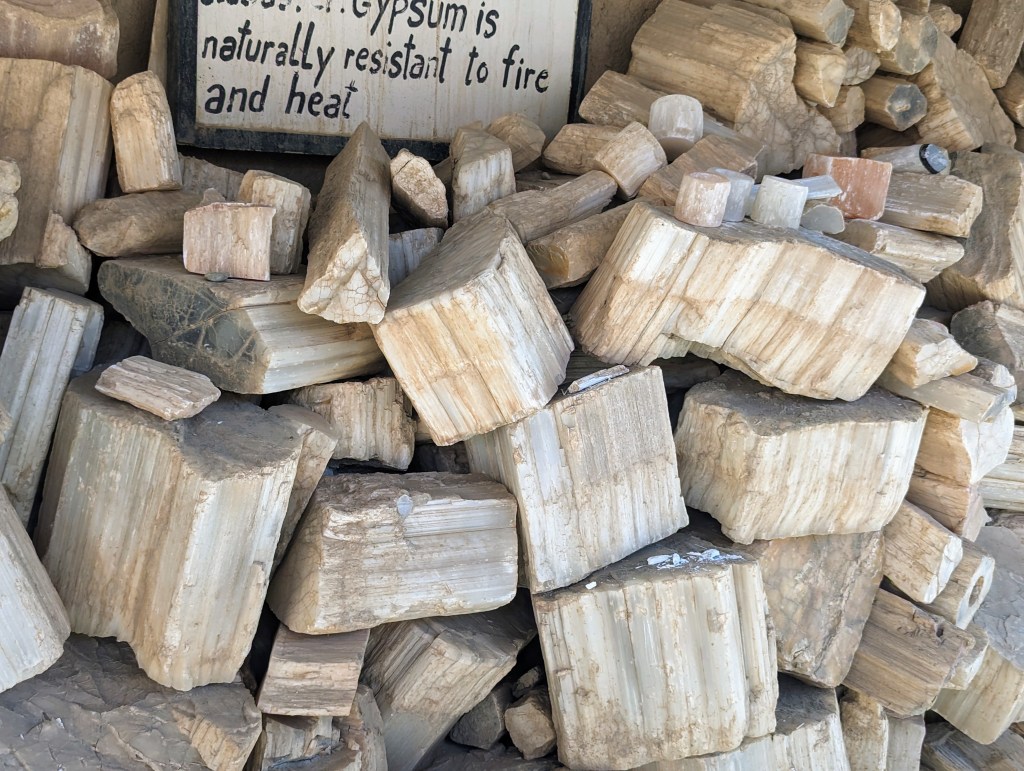

Common minerals include gypsum.

and sand rose.

He explained how the fossils are found in the rocks, often discernable by their shape or a crack in the rock.

The they are sliced open and polished.

They can then be incorporated with marble or minerals to form decorative items

useful items like sinks

and tables

The shop is chock full of so many items we did not know where to look next. There were serving dishes of all shapes and sizes.

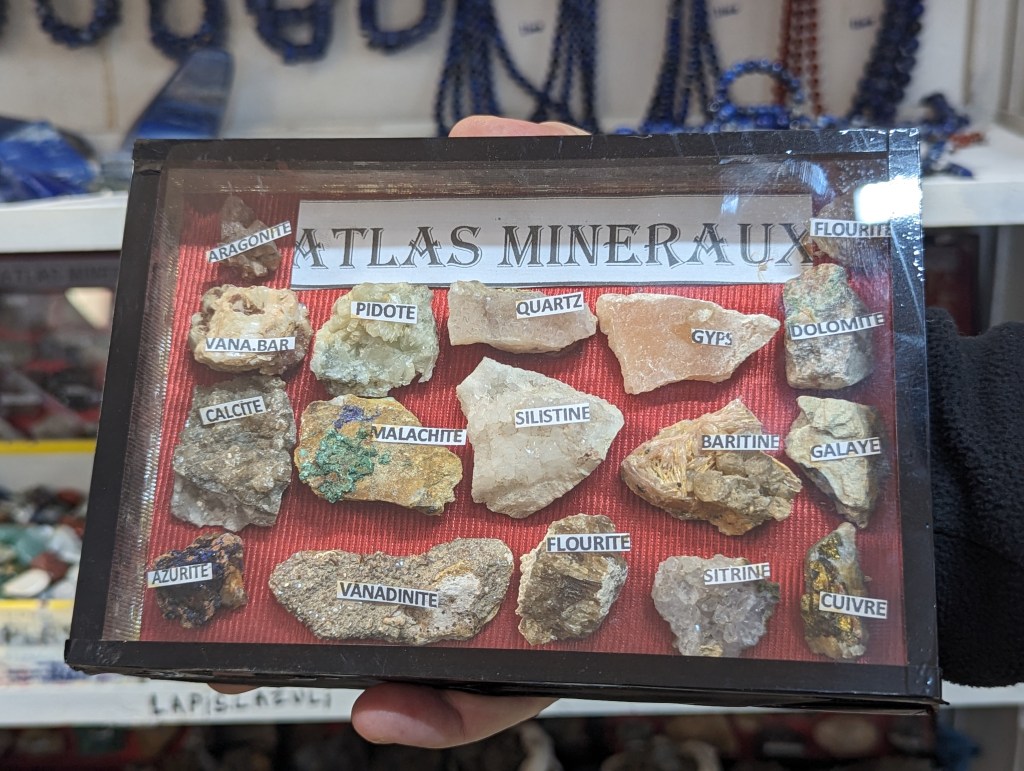

and tons of crystals and minerals.

We could have spent hours in there, but alas, it was time to move on. We next drove through Rissani.

Rissani is the spiritual capital of the current kingdom being the birthplace, and now resting place, of the first king of this dynasty. Rissani is the ancient capital of Tafilalet; its location as a crossroads between north and south on the caravan trading lines of gold, silver, and produce headed west to Marrakech and salt headed east gave the city a certain importance in previous times.

As we continued our drive we passed a road sign not likely to be seen at home.

We saw a group of dromedaries in a pen. Kamal would not let us call them camels (even though even some locals do) explaining that camels have 2 humps. Dromedaries have only one hump and are slightly taller and slightly faster than camels. A dromedary can drink 30 gallons of water in 15 minutes. The hump is both fat and water which can be broken down to sustain the dromedary for 3-4 days in the desert without food or water. There are about 15 million dromedaries in all of Africa (camels are mostly in Asia). No dromedaries currently live in the wild. They are all owned and used now mostly for tourists, at least locally.

We drove into Merzouga and got our first glimpse of the Sahara Desert. The layer of black rock on top of the sand is volcanic. The “mountains” in the distance are actually sand dunes.

We drove to Tata’s home. He invited us in for lunch.

When we washed for lunch we were amused to see that he has a fossil sink in the bathroom.

He showed us the ingredients that would be included in our meal.

While his sitser started cooking (and I was madly taking notes) Tata completed the tea ritual.

The star of the meal was to be a local specialty: mefouza. His sister began with making the dough.

She also began cooking three different veggie sides: eggplant covered in a marinated tomato sauce, peas with herbs and spices, and peppers. Tata’s son is her helper.

All three are cooked on charcoal in a clay cooker, a majamar, right inside the home.

She then rolled out the dough and started the assembly. First the spiced ground meat topped with boiled then baked almonds.

Next sliced hard boiled eggs.

Then covered with a second layer of dough which is pressed on the edges into the first.

Finally, it is baked in the oven out in the courtyard.

What a beautiful courtyard Tata has, full of date trees from Ziz Valley as well as herbs in his garden.

We sat down and enjoyed our best meal yet in Morocco, and that is saying a lot because we have loved the food!

After lunch we hopped into the 4WD vehicle that was to take us into the desert to our camp.

And we were shown to our tent, complete with shower, sink, and toilet.

Even in the desert we were welcomed with tea, almonds and cookies.

And dusk approached we were introduced to our dromedaries for a ride out onto the dunes.

From the top of the dunes we had a great view of the High Atlas Mountains to the east.

And a beautiful sunset over the sand dunes to the west.

The sand changes color as the sunlight recedes.

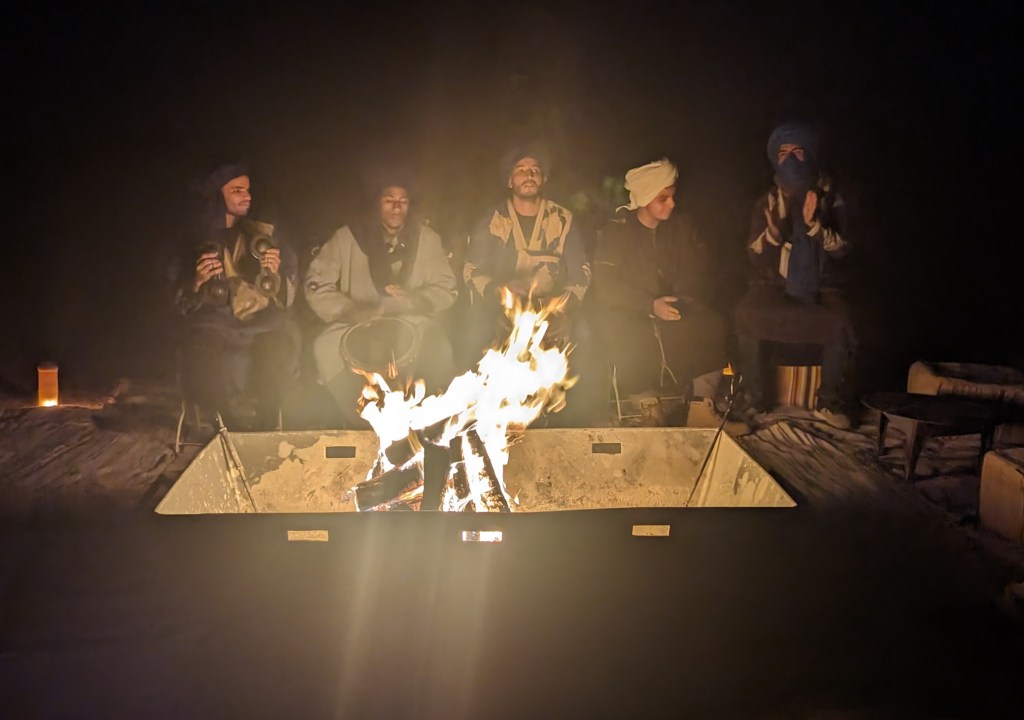

As we re entered camp a bit chilled, we were happy to see the campfire lit.

After dinner there was music and dancing by the campfire.

The families dancing with us were from Mount Vernon, NY and Norwalk, CT, small world.

In the morning we took a short walk east to watch the sun come up. We fist passed this beautiful desert flowering bush.

The sun came up over the High Atlas Mountains.

After breakfast we followed Tata through the desert. We passed irrigation fields of newly planted olive trees. Tata explained that there is a river that runs beneath the desert only 7-10 m deep. One can tell where the river is by looking at the plants. Many wells have been dug in recent years to access that water.

We could see lots of other camps in the distance as we walked. Tata told us that so many camps were springing up so fast that the government had come in to regulate them now.

We reached our destination which was the home of nomads. Tata explained that historically nomads made their living by breeding and raising animals and selling them at market to support their needs. When the grass ran out in an area, they would move to near another town. But today the nomads continue to breed and raise animals, but a lot of their income is from tourism (like our dromedary guide of the previous evening) and from farming. They are able to stay in place and afford to buy feed for the animals.

We were introduced to Hamid and his mother Zahara and were, of course, served tea. Hamid was recently married. His wife is continuing her studies remotely from here. Yes, there is cell service and wifi, albeit not fast, here in the desert. This doll is a representation of a nomad bride.

I have not yet mentioned cats, which are ubiquitous in Morocco, loved by everyone. They roam the streets of every city we have visited. We have been told that they are fed and cared for but almost never allowed inside. In the cities they keep the rodent populations low. I was surprised to see a cat in the desert, however. I was told that they are brought to the camps to kill the snakes and scorpions; well that’s a good thing! Scorpions in Morocco are not poisonous, but their bite still hurts a lot.

After tea we strolled out to the date grove.

Hamid told us that solar panels are used to power the pumps for the wells.

This well was dug by hand in about a week and is about 7 meters deep.

Solar energy is also used to run the irrigation systems.

This old well is covered because it had a butane powered generator which is no longer used.

In addition to irrigation for the date trees, there are several other crops grown for veggies and herbs for the family.

A big cash crop is henna, which is particular to the desert soil.

Once harvested, the henna plants are taken into this henna factory and hang in cool, dry rooms.

Hamid then explained that the leaves are separated from the seeds. The seeds are re-planted.

The dried leaves are then separated from the stems and made ready for shipping. Ultimately the leaves will be ground into a powder which will be the base of the henna product.

On the way back to Hamid’s home we passed this structure. Tata told us that there had been a flash flood not too long ago. The wall of this building was damaged by all the water. As the outer layer is peeled away, the mud brick base of the construction is revealed.

Because it was so windy, Hamid decided to serve us lunch inside his home rather than the tent. His mother and wife had prepared a meal of couscous, veggies, and chicken. In the corner of this room are all the rugs and blankets used for sleep. There is no heat in a nomad home. The walls are such thick mud and the windows so small it is cool in the summer and somewhat warm in the winter.

On the other side of the room is the battery storage for the solar power for electricity after the sun goes down.

The roof is made up of wood beams covered in bamboo and palm fronds which are covered by a layer of plastic then a layer of mud on top of that. After rain, which is rare, the roof almost always needs some repair work.

After lunch we retraced our steps though the desert to our camp, about an hour hike. We rested up before dinner, more music, and another night in the desert.

In the morning we were up and out early because we had a very long drive ahead of us. We left Merzouga, drove back though Erfoud, and headed west. We passed by an ancient khattara which is a series of wells and underground tunnels used in the atlas desert region for irrigation. These are all dry and unused currently.

We next drove to the very fertile Todgha Valley through which flows the Todgha River.

On the other side of the valley from where we were driving is the town of Tinghir, which is where Kamal lives with his family.

He explained to us that every family has a plot of land in the valley that they can farm. Because many families have outgrown their plots of land and the young no longer necessarily want to farm, a lot of the younger Moroccans work in Europe, send money home all year, then come home for the summer holiday. The area is also known for silver mines, which add to the affluence.

He then drove us up to the Todgha Gorge.

We then drove to a friend’s restaurant for lunch.

After lunch we drove through Dades valley, another very fertile spot full of almond trees and the fig capital of Morocco.

Then we drove past Kelaa Mgouna, Morocco’s rose capital known for its annual Rose festival in the Spring culminating with the crowning of Miss Rose. The town produces many roses and rose-scented products. Even the taxis in town are pink rose colored. At last we arrived in Skoura and drove out to our next hotel, Le Jardins de Skoura.

As one would expect from a hotel called Le Jardin, the gardens are gorgeous.

And they grow a lot of their own veggies and herbs.

The restaurant was quite cozy with a fire lit every night and the table set with scattered flowers.

In the morning we met Abdo who was to be our Skoura Valley guide. He told us that the Skoura Oasis, aka the Skoura Palmeraie, is a 25 km2 man made oasis because it is derived from irrigation systems shared by the families living here to water their land. Initially the land was divided into plots for each family. But with each new generation the plots gets divided and re-divided then passed with marriages between families. So now any individual may own several plots of varying sizes throughout the area. Most of the plots have become too small to sustain a family. So similar to the Todgha Valley, young people are being forced into the cities and even Europe to help their families financially. The irrigation system is ancient and complex. Each family gets 12 hours of water every 2 weeks. They have to divert the water to their various fields by moving mud and rocks to force the water to flow in the desired direction. Below is a length of irrigation not currently in use to show how rocks are placed to divert the stream.

And below is water flowing through a particular pipe.

In the picture below rocks and mud prevent the water from flowing into the pipe on the right.

In order to preserve the water allotted to them, the families form mini plots within their larger plot to assure the entire plot gets adequate water and to hold the water in place. Below is a recently irrigated field showing how the mini plots are formed to hold the water.

When the plants first come in, the mini plots can still be seen. Below is a relatively young field of alfalfa, which is a very common plant used for feeding livestock.

As the alfalfa matures and fills in, the irrigation wells become less distinct.

The life here is agrarian and families are interdependent. It happened to be olive harvesting while we were walking around. Families all join in the harvest and neighbors join each other with laughing, music, and sharing the meal breaks. They do not like to be photoed, so we were respectful. But almost every family offered us to stop and share their second breakfast with them. Moroccan farmers eat 5 meals a day: first breakfast is 7:30 before work, second around 10:30, lunch about 1:30, dinner after work is done, and supper after evening prayer. The olive harvest involves dropping plastic tarps around the base of the olive trees and raking the tree with poles to drop the olives. I did take a picture of the equipment. In the picture below the harvesting pole is hard to see but it is lying horizontally in front of the tree on the left.

Black olives come from the same trees as green olives, just harvested later. The green olive gives the higher quality oil but much less quantity. Because of the drought and the diminished crop, the olives being harvested here are all black because they chose quantity over quality this year.

Other common fruits grown in the region include figs, apricots, and pomegranates.

The apricot season is the shortest, lasting only 7-10 days, usually in March. The locals call anything that is joyful but very short, like a wedding festival, “like the season of apricots.”

Almond trees are also found growing in this valley.

Underneath the almond tree above are fava bean plants. Fava beans are a staple in the local diet. They can be dried and eaten in soups and tagine stews all winter for hearty meals. The plants in the shade of the tree will grow leaves but will not flower and grow beans. Something that does not thrive or do well is referred to locally “as the fava plant in the shade of the tree.”

And of course date trees are plentiful. One tree can produce thousands of dates.

The date tree grows 1-2 levels of branches a year. So one can tell the approximate age of the tree by the number of rows. The dead branches are removed each year and used as firewood or for roofing material. The stumps left behind are used for climbing. Date trees come in male and female. Only the females produce fruit, so of course are preferred. The farmers do not keep enough male trees for fertilization to happen naturally by wind. So in the spring, the farmers climb the male trees, collect the pollen, then climb the female trees to fertilize the seeds.

One cannot tell from a seed if the new plant will be male or female. Also, planting a seed would take years to get to an age of producing fruit. So to propagate new trees, the farmers remove daughter offshoots from the mother tree, then plant them in a new spot with lots of water. This is also done in the spring.

Oleanders are a common wild flower. The flower is beautiful, but both the leaf and the flowers are somewhat toxic. The locals say that someone who is beautiful on the outside, but not such a nice person, is “like an oleander.”

Birch trees are not very common, but are used to make furniture. They are one of the few deciduous trees locally that provide a bit of fall foliage.

The plant doing most poorly is the cactus. There is a fungus that has affected the cacti, killing them in droves. The cost of the fruit of the cactus seen below has gone up 10 fold in just the last 2 years.

The locals build their homes the same way they have for hundreds of years and similar to what we had seen in Ziz Valley and the nomads. They use local mud mixed with straw. Then it is either placed into flat molds and left to dry in the sun for a few days or arranged over layers of bricks.

For a more solid wall, clay is used for blocks, which would be too heavy to move, so the clay is tamped down into vertical molds. Once set, the molds are then moved to the next section.

The 3 slats at the bottom leave behind holes in the wall which allow air flow which helps the wall dry faster. In the restoration walls we saw in the north, particularly city walls, not home walls, those hole were left because it is felt that they allow expansion and contraction in freezing weather. But here in the south or in homes, the holes are filled in with mud to ensure better insulation.

Split palms make for good ceiling beams and door frames. The split wood is soaked in salt water for 2-3 weeks to prevent future termites. Roofs here are built basically the same as those of the nomads described above.

As one can imagine, none of this holds in heavy rains, but there is little of that here. If one is in a better financial situation, a layer of “glue” can be coated on the outside of the home, which is protective of rain. This is often dyed.

The windows all have the grates for air and privacy. Like in the north, they were originally of wood, but most here have been replaced with metal grates as in the above picture.

Electricity arrived in the Skoura Valley in 2000. It is such a new occurrence that when the locals offer guests to turn on a light they say, “would you like me to turn on the electricity?” Most of it is now solar powered.

This is the first area in Morocco we have visited that was affected by the Sept. 8 earthquake. Abo described his own experience of feeling his home shaking. Only a few homes were completely destroyed. Below is a kasbah that was mostly destroyed.

Kasbah in the south has a different meaning than in the north. In the north a Kasbah is a fortified palace or home of a king or sultan, depending on the kingdom, but basically a mini city. In the south, a Kasbah is a fortified home of any important family or dignitary. It is basically a very large home with 4 towers and it must be 4 stories high, otherwise it is just a dar. This area is called the “Road of a Thousand Kasbahs.” Many of the Kasbahs are now guest houses. But many are in disrepair. In order for a Kasbah to be sold, renovated, or basically anything but neglected, ALL of the family members must sign the appropriate papers. But because the families are large and now generations have passed, some of the kasbahs have been inherited by over 100 individuals who may either disagree as to the disposition of the kasbah or in some cases family members cannot be found or reached.

After walking around the valley all morning, we stopped in to visit a potter who makes ceramics in the same way as his father and the 3 generations preceding him. He obtains his own clay from the local hills and transports it back on his donkey. He then breaks up the pieces by pounding with a heavy log.

He uses a sieve to get a pile of fine dust.

He then mixes the dust with water.

He kneads it very much like dough for bread. Then he spins his wheel manually using his feet. The wheel he uses is an old tire wheel because it is much lighter than the one use by previous generations. His young daughter is his helper.

While he shaped the clay, Abdo served the tea brought out by his wife. No visit to any Moroccan home is without tea.

The item he made today is a majmar: coal pot for cooking tagine on top.

The finished item will sit in the sun for a couple of days. Sunday he will light the fire in the oven to fire all the products. The heaviest items are placed first into the bottom of the oven.

He uses dried herb plants from the area for a very hot fire.

Then he is ready for the market on Monday.

Upon leaving the potter’s home, we passed a mosque. The Skoura Valley is divided into several regions, each with their own mosque and elementary school.

The Imam’s home is right next to the mosque. The Imam’s home is identified by the dome shaped roof.

The elementary school is brightly painted making it a cheery environment for the children who walk or ride bikes to and from in groups – up to 5 km each way for secondary school – and go home for a 2 hour lunch break in the middle of the day.

We passed an area with a view of the High Atlas Mountains. Abdo told us that usually they have snow on them by this time of year, but it has been unusually warm this year. It has only snowed in the Skoura Valley once in his lifetime of nearly 30 years; it was in 2018.

The last thing Abdo showed us on our way back to our hotel was a system of wells for irrigation used in ancient times before the current system. They looked very much like the khattaras we had seen outside Erfoud but on a smaller scale.

We enjoyed another relaxing evening and dinner by the fire before heading out the next day. In the morning before leaving the Valley of the Kasbahs, we payed a visit to Kasbah Amridil, which made an appearance in 1962 in the film Lawrence of Arabia.

Kasbah Amridil was originally founded in the 17th century as a ksar: a fortified village. In the 19th century a prominent family from the ksar was chosen for the privilege of building a kasbah. The same family still lives in one section but has opened the remaining sections as a museum showcasing the traditional architecture of the building and local traditional artifacts. The ksar has fallen into disrepair. A guide of the museum first showed us some of the artifacts in the entryway. An olive press

and the wheat mill

and a butter churn

We then entered through the main door. Because a kasbah is a fortified structure, the walls are very thick, especially at ground level. All kasbahs walls are somewhat pyramid in shape, narrowing to the top. The thicker walls are needed for security more at ground level, but also for the stability of the structure and also have the added effect of having better insulation nearer the ground and more air flow at the upper levels. The ground floor walls are a minimum of 50 cm thick.

This original door also has a double deadbolt and keys.

The first level of the kasbah is for the animals with a stall right in the center open to the sky for air flow (odor reduction) with a post to tie the animals onto. The surrounding rooms are used for smaller animals, to store feed for the animals and wood for the stoves.

The stairs to the upper family rooms are purposely uneven so an enemy that might breach the door would stumble and make noise on the ascent. Originally there were no handrails. They were added later for tourists.

Above the stable is the kitchen.

The round oven in the corner, similar to the one in Tata’s home, is used for guests or special occasions because it is inefficient with the use of wood/heat. The everyday ovens can make several loaves of bread at once by placing the dough against the heated side walls creating a saddle shaped loaf.

A double boiler steamer is used for couscous.

Fridays in Morocco are couscous days when the family gathers after mosque to eat a large meal of couscous and steamed veggies, and meat if they can afford. Everyone eats off the same platter from his/her section. This is a tradition that has survived for centuries.

The tagine is cooked on a majmar similar to that made by the potter in the village the day before, although this one is metal. It is amazing how little has changed in the kitchens of the villagers in several centuries.

The poles in the center of the kitchen are for hanging meat for smoking. The smoke not only preserves the meat, it has the added effect of protecting the wood ceiling from termites.

The dining room is the long room off the kitchen. The family sit on rugs on the floor.

In this dining room some artifacts are displayed including this for hanging milk to make cheese.

and this juicer

And this item for washing hands before the meal. Water is poured over the hands into the bucket below. We have actually been offered similar washers in homes we have visited.

Also on display here are the quran school tools. When learning the quran, the child writes out the verse on a wood tablet then memorizes it. Once memorized, he must be able to recite it to the instructor. If successful, he then washes the tablet clean and moves on to the next verse. If unsuccessful, the bottoms of his feet are slapped with palm fronds, and he must go back and try again.

The ink for the tablet was made from burning sheeps wool to cinder then adding water. The pen was a small piece of bamboo.

The upper courtyard above the kitchen was used for the madrasa, the quranic school.

In each of the for tower corners on both of the upper levels were the family bedrooms. Typical Muslim families are multigenerational living together. In addition, polygamy historically was not unusual. Today in Morocco, polygamy is legal up to 4 wives. But the rules are that the first wife must give permission and all of the families must be treated equally with regards to home, finances, etc.; they do not all live together anymore. With these restrictions, polygamy now is less than 0.5% of all families; the first wife usually today only gives permission if she is unable to have children.

Most kasbahs by definition have 4 towers. This one is unusual in that it has a fifth tower

within which is a latrine for the women only; the men go outside.

The hole style latrine begs me to make an aside here about bathroom facilities in Morocco. We had been warned before arriving that squat toilets, which are basically shaped like a shower stall with a hole in the center, are the norm and toilet paper is often unavailable. Kamal has gone out of his way to find tourist friendly bathrooms along the way. But we were surprised that even when seat toilets are available, squat toilets are often also available at the same location. Kamal explained to us (when one spends as much time in the car together as we have with Kamal, no subject seems off limits) that before entering the mosque for prayers, a Muslim must perform ablutions, ie cleansing. There is usually a fountain or at the very least a bucket outside the mosque. First the face is washed, then the hands, then the feet. For obvious reasons, one does not wash one’s genitals standing outside the mosque. But it is assumed that the genitals have been cleansed. Beside every squat toilet is either a water spray, or a spigot, or again, at the very least, a water bucket. Kamal explained that Muslims find it easier to clean the genitals with more room to move squatting than sitting. The lack of toilet paper is because water is used instead. Most carry a towel to dry themselves.

Back to the kasbah. On this upper level, the walls are much thinner in places.

The original windows are quite small and slanted downward making it difficult to fire in but easy to spy on an approaching enemy.

The upper courtyard also has a drainage system that whisks rainwater away to prevent erosion, but also to be stored.

The decor on the top of the kasbah shows that it was a muslim family. If it were a Jewish family, and there were many in the region, the decor would have been a simple triangle.

From this upper courtyard, the ruined ksar can be seen. In it would have lived all of those who would have served this prominent family.

Outside the kasbah is this very old tamarisk tree. The wood from the tamarisk tree is very strong and good for doors and ceiling beams. The seeds are used for hair dye. The tree grows well in salty and alkaline soils.

Then we hopped back in the car and headed toward Zagora on the edge of the desert. Leaving Skoura Valley we passed the Nour Power Station. At 510 MW, and costing $9 billion to build, it is the world’s largest concentrated solar power plant. We had just a glimpse from the road.

The first town we passed through was Ouarzazate. Upon entering town we drove by the Taourirt Kasbah, which means “up on the hill” in Arabic. Originally built in the 17th century, it was renovated by the Glaoui family in the 20th century. They were the “Kings of the Atlas” during the French Protectorate period.

Historically the route we are traveling on was the Sahara caravan trading route. Ouarzazate was a major stop because it is where the Dades and Draâ Rivers cross. But today Ouarzazate, which means quiet in Arabic, is know as the Hollywood of Morocco, “Mollywood.” We passed a film school on the outskirts of town. There is a clean modern airport. And there are several large movie studios in town.

Next we drove to Ait Ben Haddou Ksar. This ksar is a traditional pre-Saharan habitat. The houses crowd together within the defensive walls, which are reinforced by corner towers. Ait-Ben-Haddou is a striking example of the architecture of southern Morocco. First we stopped for a scenic pic from afar.

Then we parked and hiked to the ksar.

And then climbed to the top. Unfortunately the top crumbled in the Sept. 8 earthquake and has yet to be restored.

But there are panoramic views from the top.

Once back in the car we continued along the Draa River Valley.

This area is typically lush with Date Palms, but the drought has been severe and affected this area particularly harshly.

At last we arrived in Zagora and checked into the Azalai Desert Lodge.

Alas, we were there one short night, then headed on toward the desert. Kamal left us in the hands of local desert driver Hussein. He took us first to the town of Amerzou where local guide Abdo showed us around the Kasbah, which here is more like those in the north, a mini walled city. Inside he showed us the ancient synagogue. The hole in the wall was where the torah was kept.

The door to the home below also speaks to the community of jews that once lived here.

What was most interesting in this tiny town was the hidden huge cooperative that sells all kinds of artisanal wares.

When we first entered there were men repairing old doors.

The coop guide (yes, our driver left us with a city guide who in turn left us with a coop guide; lots of people to tip) explained to us that before leaving for Israel in the 50s, the Jews taught the locals some of thier crafts including not only woodwork, but also silversmithing. Today the coop is a combination of restored antiques and newly crafted items. Many of the antiques are Jewish themed.

This samovar is in the style of those from Russia.

There were so many rooms in this coop! Like this one full of jewelry.

And this one filled with rugs woven by local women.

The next town we stopped in was Tamegroute, which is famous for the green pottery. But first we were shown, by yet a new guide Ashit, the Zaouïa Naciria. Since its creation, Zaouia Naciria has played a pioneering role in the different fields of science and thought, in addition to its religious and social mission. It was the place where scholars and students converged in search of knowledge in view of the precious documents and works with which it abounds, which made it an important Sufi and science center in the Draâ region and a crossroads for commercial caravans.

The library holds and preserves over 4000 manuscripts. Founded by Ahmed Naciri in the 17th century, the collection includes valuable secular works of medicine, history, and theology in addition to illuminated qurans, written on gazelle skin. There are works of astrology, astronomy, mathematics, and pharmacopeia, some of which date back to the 13th century. The oldest Quran is from Cordoba in 1075. The calligraphy and colored illustrations are beautiful. Unfortunately, pictures were not allowed inside.

We then visited the medina, which in Tamegroute is mostly underground to keep cool in the hot summers. It has both plumbing and sewage.

Just outside the medina is a cooperative of potters. The one we were introduced to was spinning his wheel with his feet below ground to keep cool.

He took us to where they were feeding the large ovens filled with pottery. He showed us the different clays that they use: both the traditional red clay, and the grey clay seen in the picture below.

The grey clay is a mixture of among other things, magnesium, copper, and selenium and sometimes mixed with flour without salt. Depending on the heat of the fire, the finished products will come out either blue, green, or green with glaze with increasing temperatures, respectively. It is the selenium that gives the shine. They are most known for their green shiny pottery.

But they sell everything in their store.

This town, like all on our route of the last few days, was a major stop on the caravan trail. They have signs pointing the way to Timbuktu claiming it is only a 52 day ride, on a camel of course.

We then met back up with Hussein who had a picnic lunch ready for us. Then it was another hour through two more tiny towns before the road ended. Then another two hours off road through the desert before we reached our camp in Erg Chigaga.

This was as remote a place either of us had ever been. Our home for the next two nights was an eco dome.

Ours was a luxury eco dome compared to those in the sister camp over the dunes; we had a bathroom attached.

Our camp included four eco domes and a dining room. The kitchen was in the sister camp. Neither camp has a well, being too far out into the dunes. Water is brought in using large containers that are hooked up to the domes using tubing. They have dug their own septic fields.

After settling in we were called to meet the camels (actually dromedaries, but even the locals call them camels). Our camel driver took us out to the higher dunes to watch the sun set.

After watching the sun set in the west, we turned around and watched the moon rise in the east.

We arrived back in time to enjoy dusk in camp then clean up before dinner.

After dinner a bonfire was lit as the air chilled quickly.

Our host in the camp was Hamid, seen above. He and Hussein slept in the sister camp. As there were no other guests, we were alone in camp at night.

After breakfast we set out for our serious camel ride, 1.5 hours through the desert, this time with packs on the camels to carry the provisions. Along the way we passed gazelles, but they were too quick and I was bouncing too much to get a picture.

Interestingly, the desert ecology changed a couple of times from pure dunes, to a dry looking brush to a rocky surface until we reached our destination which was full of acacia trees. There we met with a group of nomadic camel herders. We set up under a large acacia tree for a picnic.

Of course the teapot made the trip.

The nomads showed us how to bake bread right in the hot sand and ashes.

Kebabs were added to the hot coals.

Once the bread was finished and all the sand and ashes scraped off, it was surprisingly yummy. It had an herb and spice filling.

Meanwhile the dromedaries were making very loud funny sounding rumblings coming from deep in their throats and accompanied by a significant amount of saliva production. Hamid explained that these are mating calls. All of the dromedaries used for tourists are male; the females are kept for breeding only.

After lunch we were given the choice of a camel ride back to camp or having the 4WD truck come for us. Our tushies had chafed enough for one day on the ride out, so we chose the latter. Hussein came for us (Hamid and Hussein had cell service in the desert; we did not) and took us to the home of some of their nomad buddies.

The nomad camp has its own well, stable for animals, eating/sleeping tent, and kitchen. They invited us in.

Immediately upon our arrival the mother and sister disappeared. The father had passed away. The 3 brothers and a neighbor friend played host. Of course tea was prepared by the youngest and ritually served by the eldest.

Visible behind the tea making brother is the upright loom, which is used by the mother and daughter to weave rugs.

Time for an aside about the culture. Women do all the “home” work: cooking, laundry, taking care of the children, and weaving. The men do all the work “outside” the home like tending animals, trading goods at market, etc. Women are not to be seen, even at home if guests arrive. But one of the experiences most positive about visiting this family was the genuine warmth and affection exhibited between the men. When Hussein and Hamid arrived with us the were vigorously embraced. And when we gathered around for tea, the men actually snuggled together on the rugs laughing and genuinely enjoying each others’ company.

Before leaving we took a peak inside the kitchen.

Nearby was the local school for the nomad children.

They had gone home for the day, so we were able to take a look inside the classroom.

The school has its own well and a playground outside.

Once back at our camp we had some time to laze around before sunset, so Eric sent up his drone to take some aerial views of the sister camps.

And the extensiveness of the dunes.

The resident cat paid us a visit.

As the day came to a close we hiked the dunes to again watch the sun set, so very peaceful.

We were treated to yet another delicious dinner – seems like all we do is eat – and another quiet bonfire to counter the nighttime desert chill before snuggling into bed.

We left immediately after breakfast; we had a long drive ahead. We were met by Hussein who told us he had visited friends during the night and his car had broken down. So very early a new car had been dispatched to pick us up. Along the way we stopped to see a natural spring bubbling up out of seemingly nowhere here in the middle of the desert, which makes it understandable that there can be so many wells here closer to the edge of the desert. There are tadpoles and frogs in the spring water. There were also several nomad camps around.

At this point we were a little less than halfway into our 2 hour ride out of the desert, we had just passed the cell tower, when a bolt came off the suspension holding the driver side rear wheel onto the axle.

A third car was called. While waiting, the driver and Hussein managed to find the bolt and reconnect the suspension, but without the nut to hold the bolt in place, we still could not drive away.

Over 2 hours later, car number 3 arrived. On our final leg out of the desert we passed oryxes.

Kamal was anxiously awaiting our arrival in the very first town on the edge of the desert. We still had about 6 hours of driving to our next destination, one he had never been to before. We had planned to stop along the way to see saffron growing, but time was not on our side so we drove through the day and into the night away from the Sahara Desert for the last time.

Tata was our guide as well! Pretty amazing place! Love the blogs 😀

LikeLike

<

div dir=”ltr”>You are both amazing. The stories and the pictures are outstanding. And Eric….

LikeLike