We arrived in Pisa in the pouring rain, yet again. The skies were gray when we got our first glimpse of the famous leaning tower.

Eric insisted that I take at least one of the goofy, touristy pictures of him “holding up” the tower.

But the weather gods were kind to us in that the rain lightened up a bit while we familiarized ourselves with the town, walked around, and found a restaurant for a late lunch. Gone were the Ligurian cuisine items now replaced with pappardelle with wild boar ragú and roasted meats and steaks and lots of grilled fresh vegetables on the menu.

In the morning we were blessed with plenty of sunshine for our deep dive into the Piazza dei Miracoli (Square of Miracles) aka Piazza del Duomo (Cathedral Square). Pisa means mouth, which is fitting as the city sits on the mouth of the Arno River as it spills into the Ligurian Sea – although with centuries of silt flowing down the river and depositing sediment at the mouth, the city is several miles inland currently. There is archaeological evidence that the city dates back to the Etruscans in the 5th century BC. The city was a prominent maritime center as early as ancient Roman times, as described by Virgil in the Aeneid, and due to its position near both the coast and the river, maintained that status throughout the middle ages. It was at the height of Pisa’s power and wealth that the cathedral and its accompanying structures were started in 1064.

Due to timed tickets, our tour started in Palazzo dell’Opera (Opera here means “works of art”), built in several stages from the 14th century through the 19th. Originally these houses belonged to the workmen of the cathedral complex: the tailor, the gardener, the bell ringers, etc., until the 19th century when the administration offices of the Opera della Primaziale were moved in. Today it houses a lot of the original statues and artworks from the cathedral which have been replaced with replicas in their original positions to preserve their integrity. One of the first exhibited items are the bronze doors: the San Ranieri door, built in 1186 by Bonanno Pisano depicting the main episodes of the Life of Christ and originally on the entrance of the right transept of the cathedral.

Also exhibited is the Pisa Griffin, a large bronze sculpture of a a mythical beast with head and wings of an eagle but body of a horse. It has been in Pisa since the Middle Ages despite its Islamic origin of late 11th or early twelfth century. The Pisa Griffin is the largest medieval Islamic metal sculpture known, standing over 42 inches tall. Its original Islamic purpose is unknown, but in Pisa the griffin was placed on a platform atop a column rising from the gable above the apse at the east end of the cathedral, probably as part of the original construction that started in 1064.

Also exhibited in the Opera are works by Giovanni Pisano (1230-1315), and Italian sculptor who trained under his father Nicola Pisano. Giovanni Pisano built the pulpit for the cathedral as well as created many of the statues for the baptistry.

In addition to the many statues, the Opera also contained examples of the inlaid wood for the choir benches

and robes for the bishops

and the various pieces required for services.

After thoroughly familiarizing ourselves with the works and artists who created them, it was time to see the cathedral. Due to ongoing renovations work, the door usually used by the public, the San Ranieri door, was closed to the public.

We entered from the other side. Construction of the cathedral began in 1064 to the designs of the architect Bushceto. It set the model for the distinctive Pisan Romanesque style of architecture.

The mosaics of the interior, as well as the pointed arches, show a strong Byzantine influence. The façade, of grey marble and white stone set with discs of colored marble, was built by a master named Rainaldo.

I just love the details, especially the gargoyles.

The interior is faced with black and white marble and has a gilded ceiling. It was largely redecorated after a fire in 1595, which destroyed most of the Renaissance artworks.

The coffered ceiling of the nave was replaced after the fire of 1595. The present gold-decorated ceiling carries the coat of arms of the Medici.

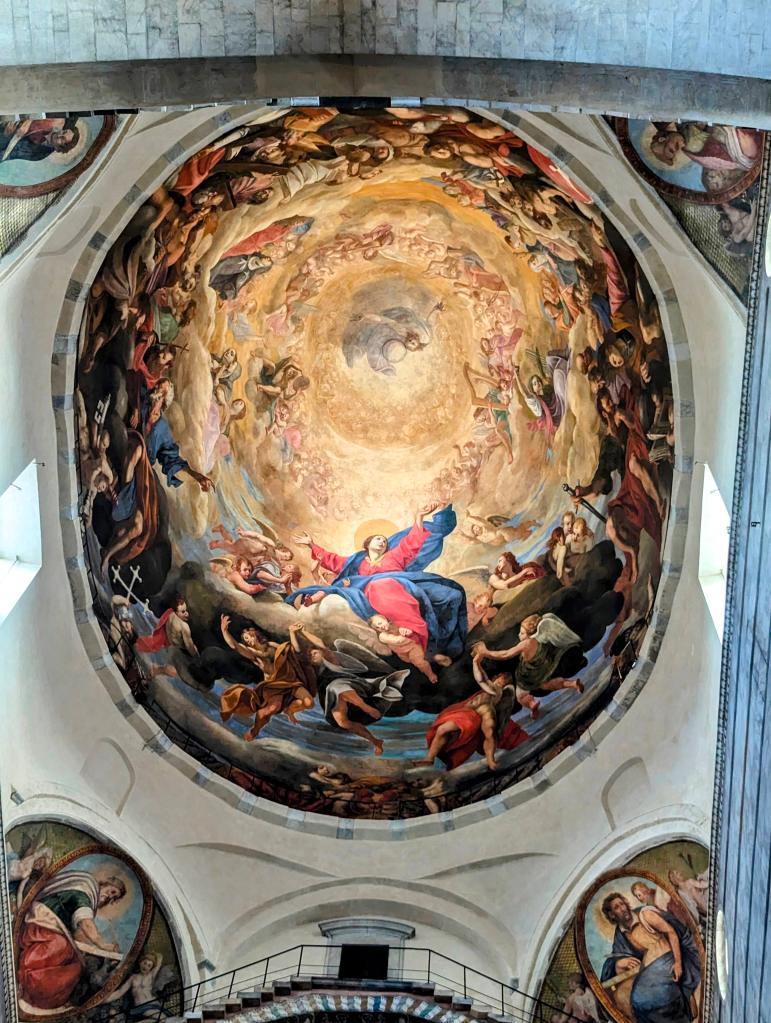

The dome has an impressive fresco.

The impressive mosaic of Christ in Majesty, in the apse, flanked by the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist, survived the fire.

The elaborately carved pulpit, which also survived the fire, was executed by Giovanni Pisano, and is a masterpiece of medieval sculpture. Having been packed away during the redecoration, it was not rediscovered and restored until 1926. The pulpit is supported by plain columns (two of which are mounted on lion’s sculptures).

The upper part has nine narrative panels showing scenes from the New Testament, carved in white marble with a chiaroscuro effect.

There are numerous artworks found inside the cathedral mostly from the renaissance, following the fire.

and, of course, the choir stalls

Madonna di sotto gli organi, The Madonna under the Organs is a tempera and gold painting on wood attributed to Berlinghiero Berlinghieri around 1220. The traditional name of the Madonna derives from its ancient location in the Cathedral, under the organs. When in 1494 Charles VIII of France freed Pisa from Florentine occupation, the Madonna, to whom a vow had been made, became a symbol of the newfound autonomy and from then on was invoked during all particularly dramatic events in the city.

At last it was time for us to climb the tower.

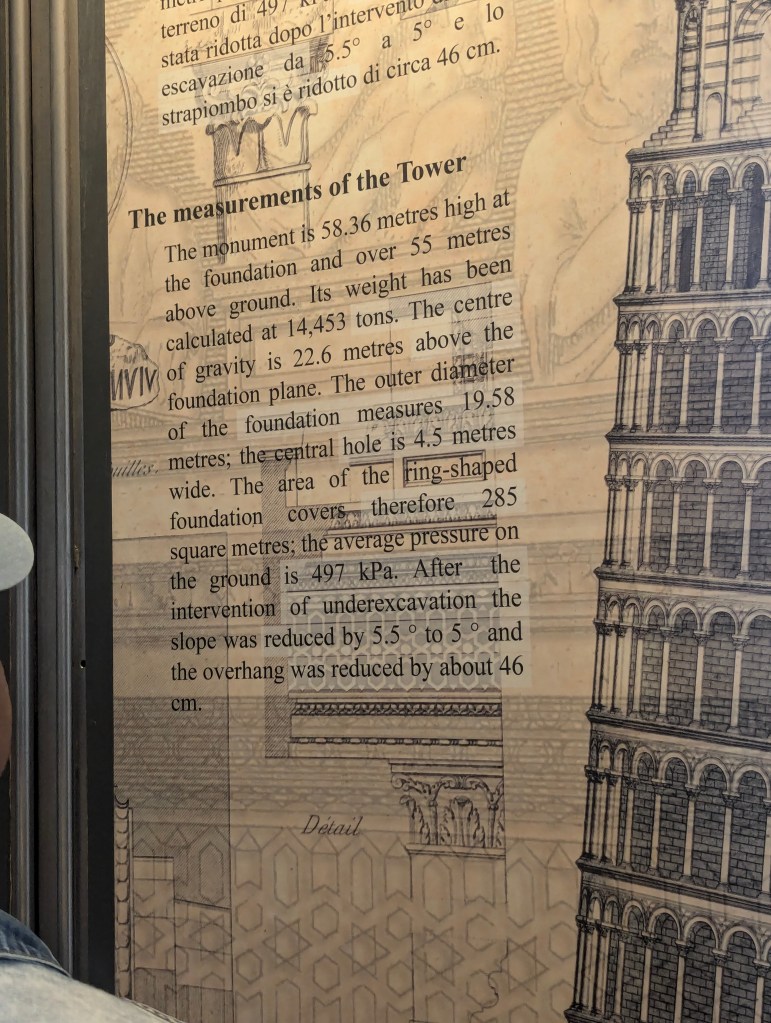

The campanile (bell tower), aka the Leaning Tower of Pisa, was the last of the three major buildings on the piazza to be built. Construction of the bell tower began in 1173 and took place in three stages over the course of 177 years, with the bell-chamber only added in 1372. Five years after construction began, when the building had reached the third floor level, the weak subsoil and poor foundation led to the building sinking on its south side.

The building was left for a century, which allowed the subsoil to stabilize itself and prevented the building from collapsing. In 1272, to adjust the lean of the building, when construction resumed, the upper floors were built with one side taller than the other. The seventh and final floor was added in 1319. By the time the building was completed, the lean was approximately 1 degree, about 2.5 feet from vertical. At its greatest, measured prior to 1990, the lean measured approximately 5.5 degrees. In 2010, the lean was reduced to approximately 4 degrees using steel beams interiorly.

This is the info provided at the base.

Oh, and there are 296 steps to the top! Once there, I was mostly paralyzed with fear.

The following views from the top are all courtesy of my brave spouse.

The tower was built to accommodate a total of seven main bells.

I was ok on the inside of the tower by the bells.

Next it was time for the baptistry, dedicated to St. John the Baptist, it stands opposite the west end of the Duomo. The round Romanesque building was begun in the mid 12th century.

Here we saw the busts and statues of Giovanni Pisano of which we had seen the originals in the Opera earlier in the day.

What was most impressive about the Baptistry were the acoustics. The was some renovation work ongoing, and one of the men had stopped for a bit and went to the central raised area and began a Gregorian chant; what an amazing sound created.

We climbed up to the balcony for a better view of the interior.

The floors were both impressive

and intriguing.

As we strode to our next stop, we noted the remnants of the medieval walls that surround the piazza.

The Camposanto Monumentale (Monumental Cemetery) aka Camposanto Vecchio (Old Cemetery), is located at the northern edge of the square. This walled cemetery is said to have been built around a shipload of sacred soil from Calvary, brought back to Pisa from the 3rd Crusade by the archbishop of Pisa in the 12th century. This is where the name Campo Santo (Holy Field) originates. The building of this huge, oblong Gothic cloister began in 1278 but was not completed until 1464.

The walls were once covered in frescoes. The first were applied in 1360, the last about three centuries later.

The Stories of the OldTestament by Benozzo Gozzoli (c. 15th century) were situated in the north gallery, while the south arcade was famous for the Stories of the Genesis by Piero di Puccio (c. late 15th century). The upper right fresco below depicts Adam and Eve in the garden.

And, of course, there are tombs

and sarcophagi

We found a grave as recent as 2009.

The frescoes are currently undergoing extensive restoration work. They survived a fire in 1944 after allied bombs dropped onto the roof. It is hard to see in the picture, but there are women sitting on the scaffolding painting and cleaning the frescoes.

Finally, we visited The Ospedale Nuovo di Santo Spirito (New Hospital of Holy Spirit) located on the south area of the square. Built in 1257 by Giovanni di Simone over a preexisting smaller hospital, the function of this hospital was to help pilgrims, poor, sick people, and abandoned children by providing a shelter.

Today, the building is no longer a hospital. Since 1976, the middle part of the building contains the Sinopias Museum, where original drawings of the Campo Santo frescoes are kept.

Alas, we had seen little of the town of Pisa, only the small area confined to the Piazza dei Miracoli, but we had seen enough.

Our next destination was the first that was a repeat visit for us. We had fallen in love with Florence when we came celebrating our 25th year of marriage. We thought the hotel we had stayed in so romantic it necessitated a repeat visit. Plus I was on a mission to find the perfect leather jacket I had pictured in my mind. We drove there in more rain, of course. But after checking into the Hotel Degli Orafi, determined not to be disuaded by the weather, we set out toward the four leather shops I had decided after much internet research were the most likely to have my coveted jacket. Along the path we passed a few sights familiar to us like the Fontana Del Nettuno in the Piazza della Signoria (more on the fountain later)

and some not so familiar

Within two hours I had found the jacket of my dreams in Casini Florence by designer Jennifer Tattanelli, and we were able to return to our hotel to freshen up before dinner. Once reinvigorated, we headed out again. Our hotel was almost directly across from the famous Ponte Vecchio (Old Bridge).

We crossed the bridge and took in the views downriver, noting how muddy the river appeared after so much rain.

After a truly delicious dinner at Ristorante dei Rossi, we strolled around this romantic city.

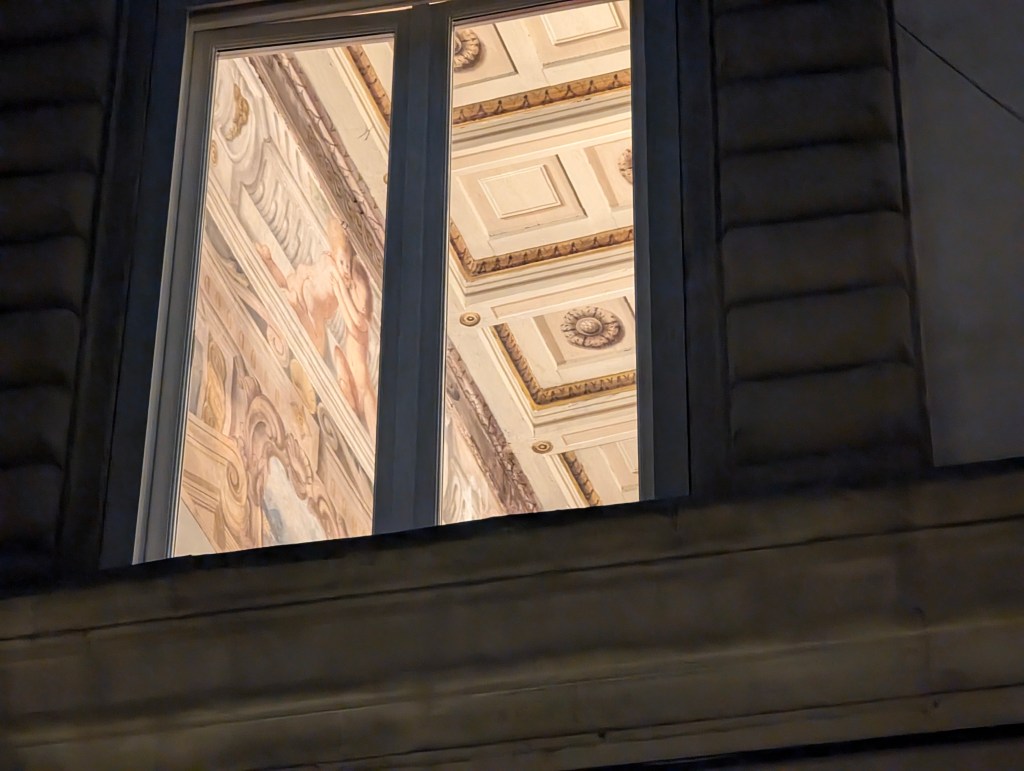

We got peaks into some of the private apartments and were once again awed by the beauty of the architectural details.

In the morning we were scheduled for a walking tour despite the still inclement weather. But first breakfast. The breakfast room at Hotel Degli Orafi is one of the many reasons we returned to this venue.

Our tour guide for the morning, Giacomo, was a student of history and architecture. Our tour was filled with fun facts starting with the Medicis, one of the most influential families in Florence’s history. The Medici Palace is closed to the public for restoration work.

But while we stood outside the palace, Giacomo regaled us with stories of how the family fortune started in the 1100s with the wool trade, but as their wealth grew, they soon became money lenders. In 1397 they became the first bankers in Florence. In the early 1400s they wanted to be the bankers for the Vatican, but two popes said no. Finally a third pope said yes, and eventually, several popes even came from the family. The Medici family’s wealth and influence grew through their connections to the papacy and the city’s elite. The Medici family held important positions in Florence’s government and used their wealth to keep their political power. They ruled Florence from 1434 to 1737, except for two brief intervals. During this time the Medici family began sponsoring artists: Donatello, Michaelangelo, Boticelli, and more.

Next stop on our tour was Cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore (Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Flower). The name Florence comes from the Latin word floreo, which means “flower”. Building commenced in 1296 and was not completed until 1436. The cathedral complex, in Piazza del Duomo, includes the Baptistry and Giotto’s Campanille (Bell Tower). The basilica is one of Italy’s largest churches and its dome, when first built back in the 15th century, was the largest ever built in western Europe. Although it was later overtaken by St. Peter’s Basilica, it still remains the largest dome ever constructed of bricks.

The white marble is from Carrera, same as the statues. The green marble is from Prato, near Florence, and the pink marble is from Siena in southern Tuscany. These marble bands had to repeat the already existing bands on the walls of the earlier adjacent baptistry.

In the middle of the 13th century building efforts were stopped as the black plague swept through Italy. Half of the population in Florence perished during that time. When work resumed almost 50 years later, one of the first projects finished was the bell tower.

During the quarantines of the plague the rich got richer, the building grew, and the hole for the dome became so immense, no one knew how to cover it. On 19 August 1418, the Arte della Lana announced an architectural design competition for erecting the dome. The two main competitors were two master goldsmiths, Lorenzo Ghiberti and Filippo Brunelleschi, the latter of whom was supported by Cosmo de Medici. Ghiberti had been the winner of a competition for a pair of bronze doors for the Baptistery in 1401 and lifelong competition between the two remained sharp. Brunelleschi won and received the commission for the dome.

It took Ghiberti over twenty years to complete the two doors which depict the life of Christ in 24 panels.

Ghiberti then went on to make a second pair of doors for the other side of the Baptistry. Those took him 27 years to complete the 10 panels. At the time the Battistero di San Giovanni (Baptistry of St. John) was finished near 1500, it was one of the most important buildings in Italy.

Filippo was originally a clock maker and goldsmith. But when he lost the door competition to Ghiberti, he went with his friend Donatello to Rome and studied architecture while Donatello studied Roman statues. When Filippo came back to Florence he proposed the design for the dome to be the first self supported dome in the world almost 300 feet high. The wool guild, ie the Medicis, were in control of the erection of the dome.

So despite Fillipo’s win of the competition, Ghiberti was appointed coadjutor of the dome and drew a salary equal to Brunelleschi’s and, though neither was awarded the announced prize of 200 florins, was promised equal credit, although he spent most of his time on his other projects ie the doors. When Brunelleschi became ill, (or feigned illness in a fit of anger over the situation), the project was briefly in the hands of Ghiberti. But Ghiberti soon had to admit that the whole project was beyond him. In 1423, Brunelleschi was back in charge and took over sole responsibility. Erection of the dome had begun in 1420 and was finished in 1436.

The ceiling of the dome, decorated with a representation of The Last Judgement by Giorgio Vasari, is one of the largest frescoes ever painted, and was not completed until 1579. The building and decorating of the dome is said to have inspired Donatello, who worked on several of the statues in the cathedral, Michaelangelo, and DaVinci.

Next stop on our tour was Piazza della Signoria, named after the Palazzo della Signoria, also called The Palazzo Vecchio (“Old Palace”) is the town hall of the city. (Old Palace v the “new” palace, ie the Pitti Pace, more on that later). It is the main point of the origin and history of the Florentine Republic and still maintains its reputation as the political focus of the city. Built in the early 1300s, the Palazzo Vecchio was the second Medici palace and immediately became the seat of the government. This massive, Romanesque, crenellated fortress-palace is among the most impressive town halls of Tuscany. Overlooking the square with its copy of Michelangelo’s David statue, it is one of the most significant private palaces in Italy, and it hosts cultural points and museums.

Also in the piazza is an open air statue gallery, the Loggia del Lanzi, which has both antique and Renaissance statues as well as the Medici lions.

At this point our guide Giacamo pointed out the difference in the anatomical accuracy of Michelangelo’s David, a copy of which is outside the palace (more on David later) and the inaccuracy of the anatomy of the Grand Duke Cosimo I de Medici depicted as Hercules defeating Cacus by sculptor Baccio Bandinelli (1493-1560).

Grand Duke Cosimo I de Medici, Duke of Florence from 1537-1569, commissioned the Fountain of Neptune in 1559 to celebrate the marriage of Francesco de Medici I to Grand Duchess Joanna of Austria. Cosimo was responsible for a vast number of architectural and artistic elements in Florence that still exist today. The fountain incorporates a series of mythological figures and iconographies that symbolize both Cosimo I de’ Medici’s power as well as the union of Francesco and Joanna. Giacamo explained how in its time, the fountain and statue were a form of propaganda, depicting Cosimo shown naked like a Greek god on earth.

Next Giacomo took us to the house of Dante (1265-1321). Giacomo explained that although the tower was built in 1086, the house was built 1865, clearly not a place he actually lived.

But when, in 1865, Italy came together as a country, it adopted the dialect of Dante, ie the dialect of Tuscany, his birth place, as the language of the now united country. Dante had written the Divine Comedy in the Tuscan dialect so the average citizen who could not read the bible, which still appeared only in Latin, could learn about the afterlife. This house was built in 1865 in his honor.

Our final stop was in the courtyard of the Uffizi Gallery, a prominent art museum. The Ufizzi Gallery is one of the most important Italian museums and holds a collection of priceless works, particularly from the period of the Italian Renaissance. The building of the Uffizi complex was begun in 1560 for Cosimo I de’ Medici as a means to consolidate his administrative control of the various committees, agencies, and guilds established in Florence’s Republican past so as to accommodate them all in one place, hence the name uffizi, “offices”.

.

He showed us some of the many statues around the courtyard which include Gallileo

and Amerigo Vespucci.

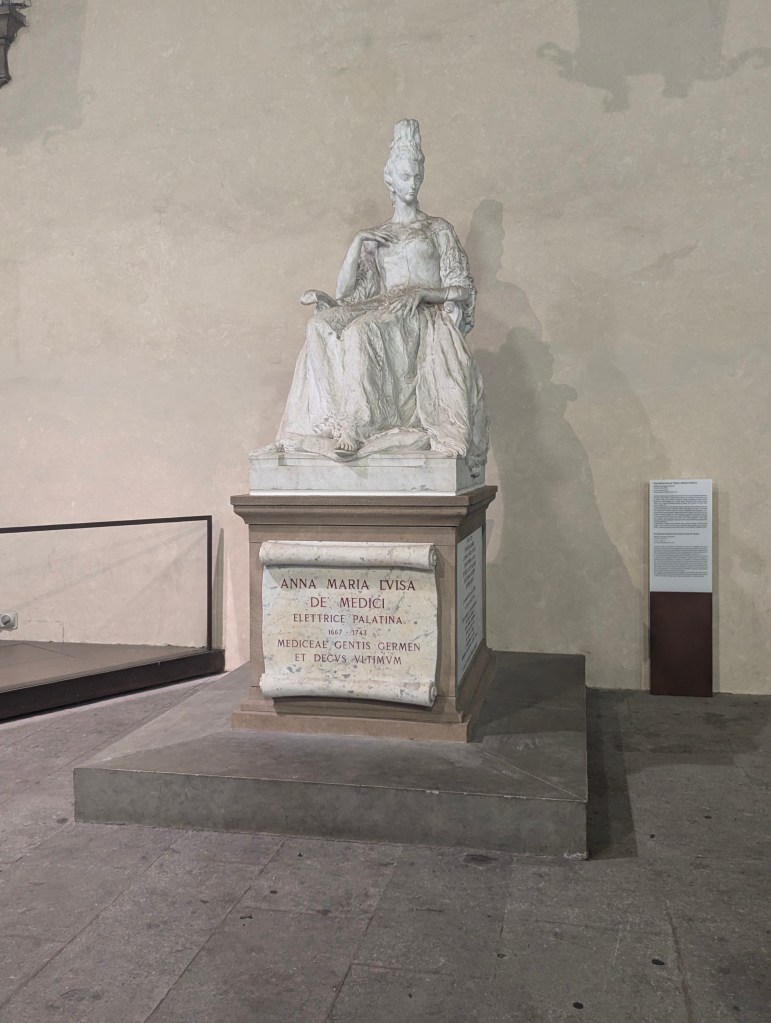

He also pointed out Cosimo I de Medici high above the arch. After the ruling House of Medici died out, many of them from syphilis, their art collections were given to the city of Florence under the famous Patto di famiglia negotiated by Anna Maria Luisa, the last Medici heiress. The Uffizi is one of the first modern museums. The gallery had been open to visitors by request since the sixteenth century, and in 1769 it was officially opened to the public, formally becoming a museum in 1865

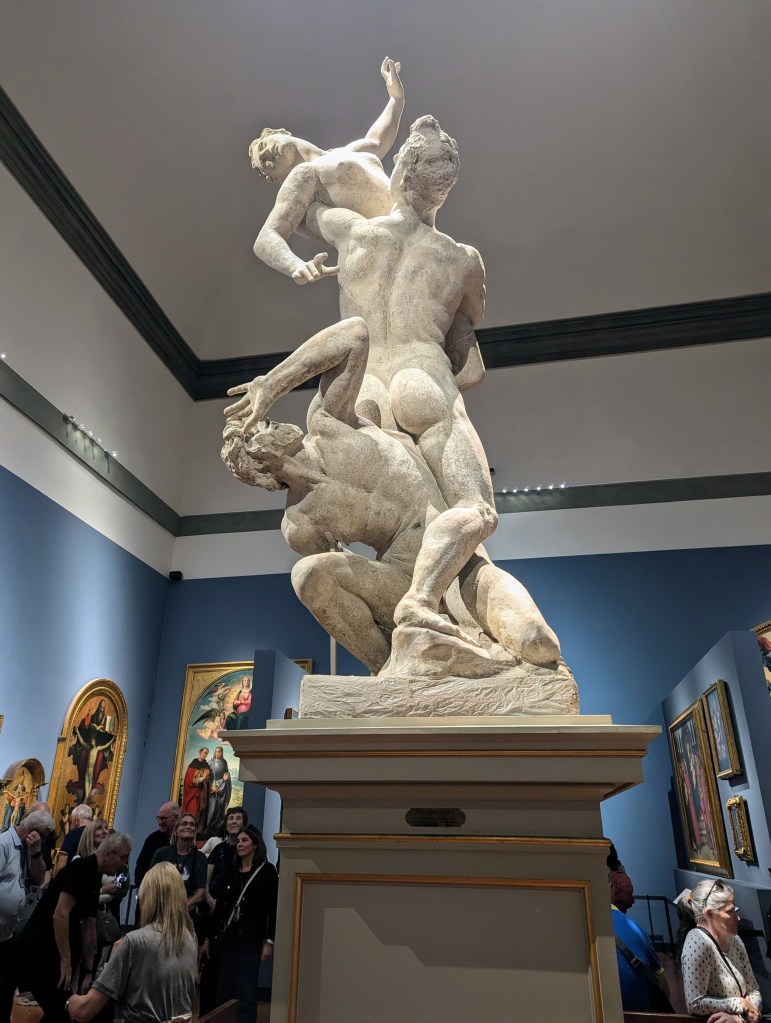

After the tour we chose not to go into the Uffizi, having done so on our first trip to Florence. But we did want to go back and revisit the David. So after lunch, we headed to the Galleria dell’ Accademia di Firenze. First we made our way through a large collection of paintings by Florentine artists. Next we saw Giambolgna’s full size plaster model for his statue Rape of the Sabine women.

The 16th-century Italo-Flemish sculptor sculpted a representation of this theme with three figures (a man lifting a woman into the air while a second man crouches), carved from a single block of marble. This sculpture is considered Giambologna’s masterpiece. The original is in the Loggia del Lanzi.

Finally we came to the works of Michelangelo including his set of 4 prisoners “escaping” from the marble.

and the Palestrina Pieta, which recently has come into question whether it is by Michelangelo.

And finally the David. The statue was originally meant for the cathedral, but it was too heavy to be lifted once finished. It was then placed in front of the Palazzo Vecchio (where the copy now stands). The Academia was built to house the David for conservation purposes, and it has been housed there since 1873.

After leaving the Academia, we wandered back to the Loggia dei Lanzi in the Piazza della Signoria to take a closer look at some of the statues there, realizing now that except for the David, they are the originals. We were particularly drawn to Giambologna’s Hercules and Centaur

and Perseus by Benvenuto Cellini (1513-1571).

We also entered the courtyard of the Palazzo Vecchio.

There we found a statue of Anna Marie Luisa de Medici, the last heiress and benefactress of the Florentine art world.

After a long day of touring, we treated ourselves to drinks on our rooftop terrace, its view another reason for our return to Hotel Degli Orafi.

For dinner we again crossed the Ponte Vecchio to the other side. Its many shops, most of them jewelry, were closed for the night.

Our first stop, after another amazing breakfast, was the Sunday Santo Spirito Market, as recommended by Giacomo. Established in Florence in June 1986, the market has been a recurring event held on the second Sunday of every month.

With over 100 vendors, the market specializes in small antiques, features a dedicated section for organic food, plants, and flowers, and offers everything from candies

ceramics

books

and vinyl

After rummaging around in the market for a while, it was time for our deep dive of the day: the Pitti Palace. Situated on the south side of the River Arno, not far from the Ponte Vecchio the Pitti Palace was the third palace of the Medicis. The palace was originally built in 1458 as the home of Italian baker Lucca Pitti. It was bought by the Medicis in 1549. It grew to be a great treasure house as later generations amassed paintings, plates, jewelry and luxurious possessions. The Medici also added the Boboli Gardens to the estate. In the late 18th century, the palazzo was used as a power base by Napolean. Amazingly, we somehow did not take a single picture of the outside of the front of the palace itself. Our first picture is of the main entrance.

What I love about visiting palaces is that in addition to the unbelievable works of art that are frescoes on the ceilings and walls, and the numerous paintings throughout, there are the household furnishings like these inlaid tables, which are just of a few of the many that caught my eye.

Just look at this urn

Oh, and the furniture is so exquisite.

We were intrigued by this “modern” bathroom installed for Napoleon.

We had headsets for audio tours and diligently listened to the descriptions of the meanings of all the allegories on all the ceilings, but honestly, who can remember much of it. Suffice it to say the frescoes are mind-boggling.

as are the many moldings and architectural details throughout.

But lost in all the glitz of the frescoes and moldings are the many, many paintings hanging throughout by Italian artists: Raphael

and Caravaggio

and Del Sarto, just to name a few.

Also included are some Flemish artists like this Rubens.

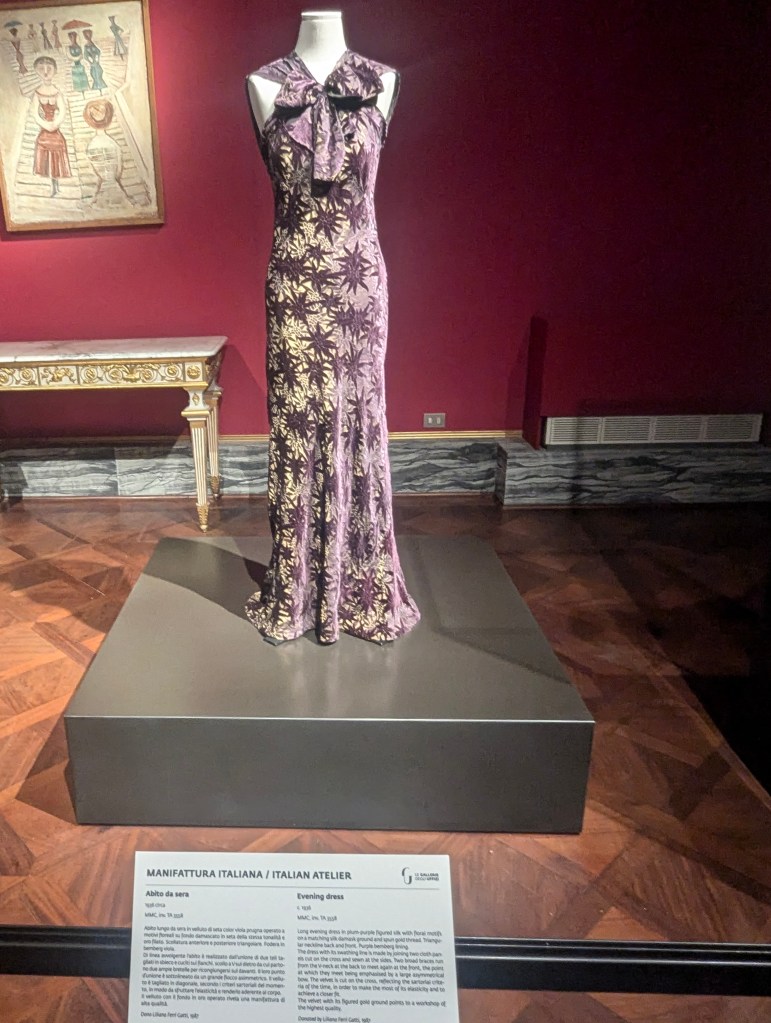

As can be seen in the picture of the urn, there ultimately was way too many paintings, way too much to look at. But before leaving the palace (after hours there) we did have to stop by the temporary exhibit which featured gowns from the 18th,

19th centuries

to the early 20th

and beyond.

After exhausting ourselves for hours in the palace, it was time for the Boboli Gardens. The Boboli Gardens were laid out for Eleanor di Toledo, wife of Cosimo I de’ Medici. One enters from the back of the palace. At the base of the gardens is a view of Florence across the River Arno.

We failed to get a picture of the front of the palace, but this is the back entrance.

The lower part of the garden has an amphitheater-like shape at the center of which is an ancient Egyptian obelisk. The garden from there climbs a long relatively narrow path with hedges and statues on both sides.

More than halfway to the top is a statue of Neptune, a contemporary to its counterpart in the Piazza della Signoria.

At the peak of the hill, the forceful Statue of Abundance stands out; Giambologna used Joanna of Austria, wife of Francesco I, as inspiration for its face.

From there this is the view of the palace and Florence beyond.

And we had not yet appreciated the extent of these gardens. We started down one side and encountered the Tindaro Screpolato, a sculpture by Igor Mitoraj (1944-2014), the only modern sculpture in the gardens. Tyndareus was the king of Sparta, father of Clytemnestra and Helen who caused the epic Trojan War in the Iliad. This sculpture is an interesting modern interpretation of an ancient story.

The path of the garden then turned parallel to the palace but moving away from it as we passed rows of trees lined with statues

both of Roman antiquity

and 17 and 18th century subjects

After much walking (the gardens cover 111 acres of land) we came to the the Isolotto, an oval-shaped island in a tree-enclosed pond.

In the centre of the island is the Fountain of the Ocean.

By the time we left the garden we were thoroughly exhausted. For dinner we treated ourselves (don’t we always) to another delicious Tuscan meal including another Tuscan speciality: grilled artichokes. It was a delicious end to the Tuscan section of our journey.

Incredible art history lesson!

LikeLike

Congratulations. Nice description of your trip, with lots of interesting point. Here is a little more on Duomo of Pisa ceiling: Yes, the Duomo of Pisa suffered a major fire in 1595 that destroyed much of the medieval roof and ceiling. The rebuilding was indeed funded largely by the Medici, who by then ruled Florence and Tuscany. Ferdinando I de’ Medici (Grand Duke of Tuscany) commissioned the work as part of his policy of integrating Pisa into the Grand Duchy. Pisa had once been a proud maritime republic, often at war with Florence, but by the late 1500s it was under Florentine control. Paying for the ceiling was both an act of piety and a political gesture—“look, we care for your treasures too.” The ceiling you see today—gilded, with wooden coffering and painted panels—comes from that Medici-sponsored rebuilding.

And, as I’m sure you noticed that the bread in Florence is without salt (pane sciocco = silly bread); here is a legend about the rivalry between Florence and Pisa. Pisa blocked Florence’s access to the sea, taxed salt, and so Florentines defiantly learned to bake bread without it. There’s a grain of truth, but historians treat this as folklore rather than fact. Salt scarcity in central Italy during the Middle Ages was real. The “salt wars” (notably Perugia vs. the Papal States in 1540) show how taxes on salt were a hot political issue. Florence may have paid high salt duties to Pisa when Pisa controlled maritime routes, but by Dante’s time (early 1300s) Florence had already secured other sources. More likely, “pane sciocco” was simply a cultural adaptation: Tuscan cuisine is full of salty, savory dishes (prosciutto, pecorino, soups like ribollita). A bland bread makes sense as a neutral counterbalance. Hence: the fire and Medici gift is solid history; the saltless bread because of Pisa’s tariffs is a persistent legend—colorful but not really provable.

LikeLike