After a 9 hour overnight flight from Miami, a mini tour of Buenos Aires as we transferred between airports, a 5 hour total layover in Buenos Aires, and another 4 hour flight, we finally arrived in beautiful if chilly Ushuaia. We checked into Hotel Los Ñires

with a gorgeous view of the Beagle Channel (named for the HMS Beagle from which Darwin collected data for his “On The Origin of Species.”)

After a shower and a bit of a rest, we headed into town. Ushuaia is a city of about 85,000 residents and loves to tout itself as the “fin del mundo”, “end of the world”; it is the southernmost city in the world. There is a Chilean town, Port Williams, on a small island across the Beagle Channel to the south with only 3,000 residents, which calls itself “beyond the end of the world.” But Ushuaians discount it as a village, not a city.

We strolled along San Martin Street, the main tourist thoroughfare for shopping and dining.

The were two products that jumped out at us as new and different. One were these vessels which are for drinking mate tea, very popular in Argentina. Hot water is poured directly over the ground, cooked leaves of the yerba mate plant, traditionally in a hollowed out gourd. The tea is drunk using a metal straw with a filter at the bottom.

The other souveniers notable were statuettes in a pink stone. The legend of the Rosa del Inca, or Inca rose, is about two lovers who were turned to stone after death. The Inca rose is a type of rhodochrosite, a pink manganese carbonate mineral. It is the national stone of Argentina.

We took in the sites along the port. Ushuaia is the gateway for nearly 300 cruises to Antartica a year as well as tours to nearby Isla Yécapasela, known as “Penguin Island” for its penguin colonies and for tours of Beagle Channel; more on both of these later.

Our driver between the airport and hotel told us Beagle Channel King Crab is a must-try delicacy in Ushuaia, so we headed to Tia Elvira by the port to give it a try.

We ordered the “medium,” which was the smallest centolla (king crab) on the menu. It was removed live from the tank and brought to the table for our approval prior to cooking. And oh so delicious and fresh!

After a much needed night’s sleep and a quick breakfast in the gorgeous Los Ñires restaurant

we were picked up for our Tierra del Fuego National Park tour. We joined a bus full of tourists from Belgium, Milan, Brazil, Atlanta, and Toronto led by our guide and naturalist for the day: Valentine. While driving to the park Valentine told us that the name Ushuaia comes from the Yámanan language; aia means bay, ush means looking to sunset. The Yámanan were nomadic Amerindian peoples who lived on the southernmost coastal and channel islands of Chile and Argentina. He also told us about Port Williams and the above mentioned title “disputes” of “southernmost” city vs village. He told us that part of the reason Ushuaia is so well populated is that the government subsidizes the cost of fuel thus keeping the cost of living much lower that it would otherwise be. Valentine also went on to explain that although the summers are quite cool, with average highs in the mid 50s and lows in the 40s, the winters are not much colder with highs in the 40s and lows in the 30s. He explained the reason for these moderate temperatures compared to cities of comparable latitude in North America, eg Saskatchewan in Canada, is because of the “ocean” conditions in the South vs “continental” conditions in the North. The ocean waters maintain temperatures more constant than the land masses.

One of the first things Valentine pointed out is the low tree line as compared to what we are used to seeing in the Rockies. The mountains here are mostly 2-3,000 feet, but the tree line is just at about 2,000 feet. That is because all of the trees here are from the same beach family and cannot grow above that altitude.

As we entered the Tierra del Fuego Parque National we saw several horses roaming about. Valentine explained that in Argentina, horses are often kept as pets and many owners do not have fences. There are no fences around the park. If a horse wanders into the park, the cost for retrieval is extremely high due to fines and fees for rangers to catch the horse, so owners often relinquish the horse to the park.

Once in the park, the horses often form herds and foals are delivered yearly. We were fortunate to see a couple of this year’s foals.

We were informed by the rangers that due to high winds and risk of falling trees along the coast, our planned route was closed for the day. We were rerouted to the Senda Pampa Alta.

Off we set for our approximately 4 mile hike into the woods. Along the way Valentine informed us that this is the southernmost and one of the youngest forests in the world because this land mass was one of the last to melt after the ice age. Because of the cool temperatures, all life evolves slowly here. Leaves take about 2 years to decompose, trees about 200 years. Between its young age and the slow decomposition, the forest floor is only about 4 inches thick. The tree roots are shallow and must grow laterally because they cannot grow into the ice age rock below (making hiking challenging avoiding them constantly). The first part of our hike contained all very young trees. It takes trees 120 years to reach full maturity.

Valentine explained that there are few bird species in these woods due to a dearth of insects, no ants. The bird species here include condors, caracaras, albatross, petrols, finches, thrushes, and the Magellanic woodpeckers. We were not fortunate enough to see a Magellanic woodpecker, but he did point out a tree stump with holes made from the woodpecker seeking the giant worms therein.

Varieties of flora we saw along the way included some orchids

and the edible chaura berries

and the also edible diddle-dee berries

Many trees had an outcropped ring, a reaction by the tree to a fungal parasite. When the infection reaches maturity, little yellow balls are formed which produce at their center a fluid, chauchau (sweetsweet) that is edible to the birds.

The formed balls develop holes through which their reproductive spores escape.

Once we reached the apex of our hike, we were treated to panoramic views including some of the first glaciers we were to see.

The distant mountains to the west are part of the Darwin Range.

While up here Valentine explained the geography in better detail. Patagonia (named for “area with big footed inhabitants” because the original Spanish explorers saw large footprints in the sand made by the Yáman, whose feet were about the size of the average US basketball player) is divided into the Chilean side and the Argentinian side by the Andes mountains. The Chilean side is generally lush with plentiful rainfall from the Pacific Ocean. The Argentinian side is 90% desert because the mountains block the rain. Ushuaia is in the lush 10%. The lower portion of Patagonia is an island (divided into the Chilean west and Argentinian east) called Tierra del Fuego (Land of the Fires) because the original Spanish explorers saw the smoke of the fires of the Yáman and thought they were volcanoes. Tierra del Fuego Province is an island bordered by the Strait of Magellan to its north and the Beagle Channel to the south.

As we headed down the south side of the hike, we passed an area with many dead trees. Valentine told us that the fauna are even fewer than the flora and originally included pumas, foxes, and llamas, which had crossed the strait of Magellan before it melted. But when sheep and cattle were introduced by farmers, the pumas were predators and therefore killed off. Then in 1946 20 beaver couples, ie 40 total beavers, from Canada were introduced hoping to start a fur industry. But as the beavers adapted to the milder climate, theirs skins became thinner and the pelts were no longer desirable. With no human hunters and no natural predators, their numbers have increased to over 200,000 today. The dams they build create areas of standing water which choke the oxygen out of the roots and the trees die still standing.

As we reached the bottom, we again passed through a young area of the forest.

And finally we came out into the channel.

We then boarded our little bus and headed to lunch.

Lunch was a delicious beef stew and Argentinian Malbec. Eric and I happened to sit across from a young Brazilian couple who turned out to both be doctors! We spent the meal comparing healthcare systems.

After lunch it was time for our paddle trip on the river. First we had to don the gear.

Once on the boat Valentine took a selfie of our group.

The mountain in the background is Condor Mountain in Chile.

Once we reached the end, we had a view of the channel.

This is also the end of the PanAmerican highway which travels 18,000km (11,185 miles) through Alaska.

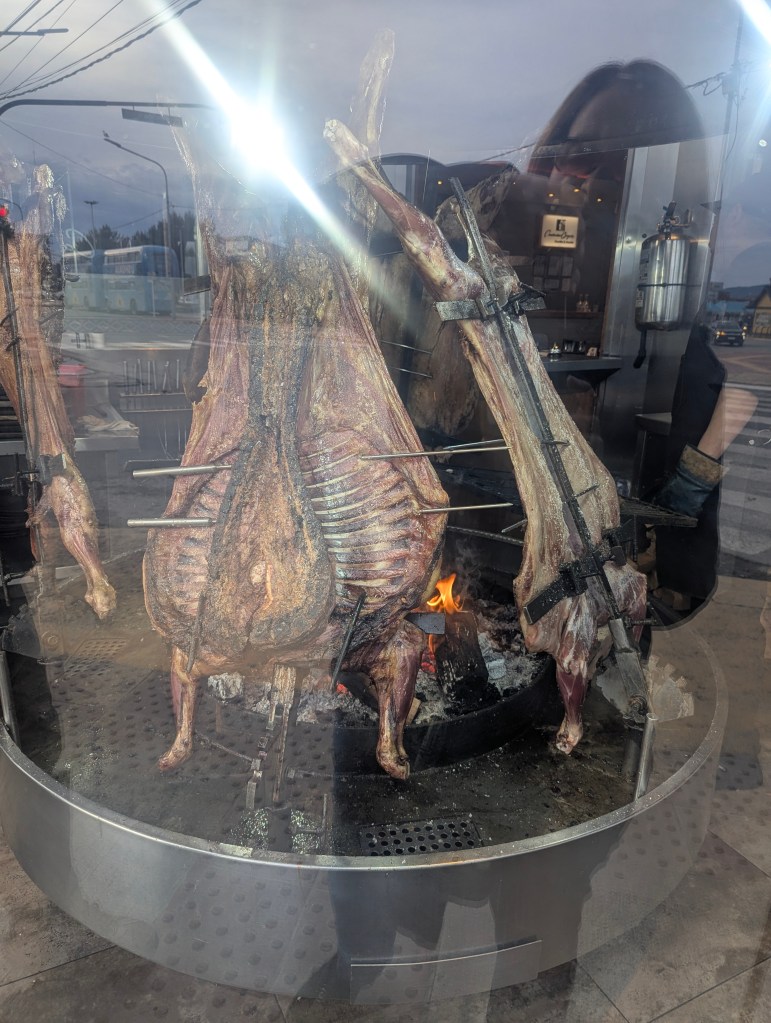

After our long day of outdoor exercise we treated ourselves to another Tierra del Fuego specialty: grilled lamb, unbelievably good.

The lambs can be seen from outside the restaurant grilling over the open fire (not my best photo due to the glass).

We were up and out by 6:30 the following morning to board a bus for our nearly 2 hour ride through the Fuegian forest (named for the Fuegian peoples, the original inhabitants, of which the Yáman mentioned above are one tribe), past peat valleys and a ski resort (there are 17 ski resorts in Argentina), over the mountains to the Estancia Haberton (Haberton Ranch).

Once at the ranch our group of 40 was divided into two. We were in the first group to board the boat to Martillo Island, ie “Isla Yécapasela” (Penguin Island).

The island is owned by the farming Haberton family. Originally the family used the island for grazing sheep. One year, after weeks of continuous snow, the height of the snow reached over 10 feet, and all of the sheep on the island died. The island already had a few pairs of nesting penguins, but subsequently the population has grown significantly. The family now restricts visitors to the island to 20 at a time and only a few visits a day. We were instructed by our guide how best to visit the penguins without alarming them.

There are two species of penguins currently nesting on the island, one migratory, the other not. The migratory species, the Magellanic penguin, are the dominant species here. It is the southernmost colony of this species in Argentina. The number of breeding pairs on Martillo Island has been constantly increasing year after year, rising from 519 in 1992 to over 7,200 currently.

The soil on the Fuegian Islands is peaty and soft, with a high content of organic matter. This allows the species to maintain a high proportion of nesting caves of considerable size, sometimes exceeding three feet in length. The green sticks marking the burrows are those of researchers who have cameras recording the nesting and mating habits. The males and juveniles are the first to return to the island starting in September. The penguins generally will return to the same nest every year although the juvenile males may try to fight for them rather than build new. If the egg is successful, after migrating up the Atlantic coast of Argentina, always within 150 feet of shore, they will return and choose the same partner the following year.

The penguins generally lay two eggs a year, but usually only one will reach adulthood. The eggs are laid in mid October and take 35 days to hatch. Both partners take turns both on the nest and subsequently feeding the juveniles for 70-100 days. The juveniles grow very fast reaching their adult size in about 60 days. The juveniles can be discerned because they have no vertical black stripe on their chest.

All penguins are white on the bottom and black on top, an adaptation that camouflages them from predators while swimming. The other species found on Martillo Island is a subspecies of the gentoo penguin, identifiable by the white patch behind its eye. They have red or orange beaks and feet. They can grow to 30-36 inches, making them second to the Emperor penguin in height. They have a life expectancy of up to 23 years in the wild. The gentoo are the fastest swimming penguins in the world reaching speeds up to 22 miles per hour. Another fun fact: they poop every 20 minutes.

Here is the only breeding colony in South America of this subspecies. The colony has grown from a single pair in 1992 to over 180 currently on the island. They do not migrate. They are able to cohabitate with the Magellanic penguins because they do not fight for nesting space. Whereas the Magellanic penguins require soft ground to dig their nests, the gentoo need firm ground and build nests on the surface using pebbles and shells.

Currently the both species are molting, a process that requires 10-15 days.

They fast while molting because they are not yet waterproof and therefore cannot fish. While they are fasting they sometimes regurgitate stomach bile leading to the greenish hue seen on their underside.

The gentoo juveniles have a grey fuzz, not real feathers yet like the one in the far middle below.

No they are not looking at us looking at them. The gentoo hate the wind and stand with their backs to it.

While on the island we also had the great luck to see not one, but five condors flying overhead. With a wingspan of nearly 11 feet, Andean condors are one of the world’s largest flying birds. My pictures are unfortunately of poor focus because they are so high in the sky.

Our hour on the island had flown by, and the boat returned for us carrying the other 20 visitors. Note how they cluster into a group as, we had also been instructed; as a group we are not perceived as predators as we would be as individuals. I only wish I could include videos here; they are so much fun to watch swimming and playing in the waves.

Once back at the Haberton Ranch were were treated to an hour-long tour of the museum and research facility of aquatic mammals and birds.

Here skeletons of animals found dead are cleaned

and studied.

One fun fact we learned is that killer whales are the only mammals besides humans to go through menopause. The grandma whale’s role is to teach the pups how to hunt.

Once the boat returned with our other half, we boarded the bus back for the nearly two hour return trip to Ushuaia where we had a delicious lunch prior to embarking a boat for our afternoon tour of the Beagle Channel. We noted the many cruise ships, all of 300 passengers or less to protect the biodiversity, headed for Antartica.

There is no net fishing in the Beagle Channel to protect the biodiversity. Tourism is the third largest source of income for the province behind fuel and fishing. Manufacturing is the fourth.

Our first stop was Cormorant Island, a meeting ground for the Imperial cormorants. Although they look like penguins: black on top and white on the bottom, they are actually more closely related to pelicans. They can be distinguished visually from penguins in that they fly while penguins cannot. They nest on the surface but unlike penguins, they do not use pebbles or shells but rather feathers, sticks, seaweed, ie softer items. The Imperial species can be recognized by their white collar and chest. After seagulls, they are the second most numerous sea birds locally .

Our next stop was to visit Rocker Cormorants, much smaller than the Imperials; they nest on cliffs. They can be distinguished by their black collar, black heads, and red rings around their eyes which grow larger in size during mating season.

Both species of cormorants live about 10 years. They reach maturity at about age 3, then the males become scouters looking for a nesting area. They mate for life. The young have a grey fuzz then molt and develop their mature colors at about the age of one year. On the third island we visited the two species cohabitate.

Next stop was Les Eclaireurs (the Explorers) Lighthouse, named by French explorers who developed the site starting in 1918. The lighthouse was put into service on December 23, 1920 and currently is still in operation, is remote-controlled, automated, uninhabited and is not open to the public. Electricity is supplied by solar panels.

On 22 January 1930, Monte Cervantes, a German cruise ship, departed Ushuaia and within 30 minutes struck some submerged rocks near the lighthouse. The ship could not be dislodged and began to sink. The lifeboats were lowered and 1,200 passengers and 350 crew were removed from the ship. Monte Cervantes sank 24 hours later, and while all the passengers and crew were able to leave the ship before she sank, her captain subsequently committed suicide. The remainder of the crew and all of the passengers were taken ashore with the help of seven Argentinian and three Chilean naval ships . At the time Ushuaia had a population of 800 inhabitants. They housed the 1,500 survivors for three days before another ship came for them. Today this small island is home to Imperial cormorants and sea lions.

Sea lions generally do not eat birds because they cannot digest feathers, so the two can live side by side. Sea lions generally eat fish.

South American male sea lions fast the full three months of the mating season because if they leave to hunt, they will loose their female partners. They can weigh up to 650 pounds. Babies are born with little fat and cannot swim; they must be fed at first. They can gain as much as ten pounds a day. Babies remain with their mother for up to one year. They do not reach full maturity, however, until about age six when they develop neck fur.

Our final stop in the channel was an island home to terns. South American terns are recognized by their black feathers on the top of their heads with all white bodies. They have red or orange beaks and feet. They are migratory and live here in the channel only for nesting. Like most sea birds, they mate for life. As a group they have an interesting behavior: to protect their young from predators, they make a huge screeching racket and fly en masse above their young. Again, I wish I could include a video.

We then had an added treat to see two-hair sea lions, so named because they have a second layer of hair, which is needed because they migrate even further south. They are smaller than South American sea lions, have smaller eyes and pointier noses.

The next day we flew to El Calafate and then transferred via a 3 hour van ride to El Chaltén, a village within Los Glaciares National Park in Argentina’s Santa Cruz province. It is a gateway to trails surrounding the peaks of Cerro Torre and Mount Fitz Roy. Founded in 1985 and with a current population of under 2,000, the village boasts worldwide popularity for the outdoor adventures available. Having arrived late in the day, we settled into our home for the next few days, Kaulem Hosteria, and headed straight for dinner, which was a delicious fresh trout covered in a spinach and mushroom gratin and accompanied with ratatouille, so yummy. Have I mentioned we are absolutely loving the food here?

There are several popular trails from which to choose. The most popular is Cerro (Mountain) Fitz Roy trail to get closer to the famous mountain which looms over the town. Standing on the border with Chile at over 11,000 feet, it was first climbed in 1952. The first Europeans recorded as seeing Mount Fitz Roy were the Spanish explorers who reached the shores of Viedma Lake in 1783. Argentine explorer Francisco Moreno (1852-1919) saw the mountain on 2 March 1877; he named it Fitz Roy in honor of Robert FitzRoy who, as captain of HMS Beagle, had travelled up the Santa Cruz River in 1834 and charted large parts of the Patagonian coast.

However that trail is considered advanced and is nearly 9 miles long round trip, so we chose the less difficult Láguna Torre route, headed for the lake, a 7 mile round trip. The hike starts past our hosteria at the base of town requiring stairs before even hitting the trail!

The start of the trail was a bit of a steep climb in a rocky, dry landscape despite rain the night prior.

Our first Mirador (lookout) was a view of the Las Vueltas River.

and the Cascada (Waterfall) Margarita. Looking closely one can actually see three areas of waterfalls.

After about 1.8 miles of rocky uphill hiking, we reached the Mirador Cerro Tore (Lookout Mount Torre).

Unfortunately most of the mountains were covered in clouds.

We hiked about another half mile when we realized that realistically we could make it to the lake, but we were never going to make the entire roundtrip, so we turned back. The weather was cloudy and threatening rain. As we descended, we got a few glimpses of Fitz Roy peaking out from the clouds.

We again passed Cascada Margarita.

And enjoyed to river views of the descent. And finally El Chaltén came into sight.

We were a bit exhausted from the hike and were happy to enjoy a well deserved steak dinner, our first in Argentina, in town that night. The next day it rained on and off all day, but due to the challenging terrain of the hikes here, we were not too disappointed to be forced in to catch up on correspondences and mosey about town whenever there was a bit of a break in the weather.

The following day we headed by van back to El Calafate. We stopped about half way on the 2.5+ hour trip at Hotel La Leona.

We had stopped on our way there, but had not paid much attention. The hotel is so named (The Lioness) because in 1877, while camping here on the bank of the river, Francisco Moreno was attacked by a lioness.

The hotel was built in 1894 by Dutch immigrants. In 1905 Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid stayed here after robbing the Bank of England in Rio Gollegos. For decades the estancia (ranch) was a meeting point for gauchos (cowboys), the US equivalent to a stagecoach stop. Today it considers itself quite the crossroads.

We arrived late in the day to our hotel Blanca Patagonia

situated high above Lake Argentina with beautiful views of the lake.

Due to the lateness of the day, we headed right into town. With a current population of about 25,000, El Calafate is a town near the edge of the Southern Patagonian Ice Field in the Argentine province of Santa Cruz. It is mainly known as the gateway to Los Glaciares National Park. In ancient times the town was called something sounding very similar to its current name which was loosely translated from the indigenous aonikenk peoples as meaning “a place for depositing human goods,” ie a trading post. The town was founded in 1927 by the Argentinian government as a place for trading wool, which was the major industry in the area at the time. In 1937 the Parques Nacionales de los Glaciares was founded; the population at the time was about 100. The town has a long history with local ranchers, ie gauchos, who still can be seen in the streets.

and are celebrated in the local park.

Local artisans sell goods handmade in the traditions of the indigenous peoples.

We had dinner at a restaurant called Pura Vida. They serve dishes very typical to this region of Patagonia: stews and pot pies served in large cast iron dishes, each enough for two people.

In the morning we were up before sunrise.

and enjoyed breakfast, included in every hotel in which we have stayed so far, in a beautiful setting.

We were met early by Nadia, our guide for the day. We drove by Lake Argentina, with a surface over 580 square miles, it is the largest lake fully within the borders of Argentina and one the country’s southernmost large lakes. Sitting at an altitude of about 580 feet, the lake has a average depth of about 650 feet with a maximum depth over 2,000 feet. The lake is fed though channels to the west by outlet glaciers from the Southern Patagonia Ice Field that move toward the channels and calve icebergs into them. The lake maintains a temperature of about 40 degrees F all year. The lake is home to perch, which are indigenous and now also trout and salmon (Chinook salmon from Canada) which originally escaped from fish farms and have made their way into the lake. The Santa Cruz River drains from the bottom of Lake Argentina across the eastern steppes and ultimately into the Atlantic Ocean. Lago (Lake) Argentina was discovered and named by Francisco Moreno in 1877.

Nadia pointed out the native calafate plant growing nearby the lake. In the early summer the plants, which grow prodigiously in the region, produce blue berries that are incorporated into many products.

As we drove close to an hour, Nadia filled us in on more of the history of the area. From the 1880s to 1920s Argentina received a huge influx of immigrants from Europe. The middle of the country’s immigrants were mostly from Spain and Italy but those in Patagonia came mostly from the UK. Ranchers were given tens of thousands of acres for animals because due to the dryness of the land, 5-10 acres is required per animal for grazing. And even then, the animals must be moved often, which is what gave rise to the horseback riding gauchos and their friends: dogs. The cattle are mostly herefords; the sheep are mostly merino. Merino sheep can yield 9-11 pounds of wool per animal per year. The current buyers of the wool are first from Italy followed by the US then China. Benneton company currently owns over a million acres. In the 1930s with the invention of synthetics the price of wool dropped precipitously. The industry in the country turned to fuels: natural gas in Patagonia, oil in the middle of the country. For Santa Cruz the industry became gold, but it was not very prosperous.

Currently the largest industry in Santa Cruz is tourism. In the 1950s some French climbers discovered the nearby glaciers. In 1981 the Parques Nacionales de los Glaciares was declared a UNESCO world heritage site, which gave a huge boost to tourism. But the biggest boost to the influx of tourism and the local economy and population came when the El Calafate airport opened in 2001. Currently they receive 14-16 flights a day during the high season, 4-5 daily in the low season.

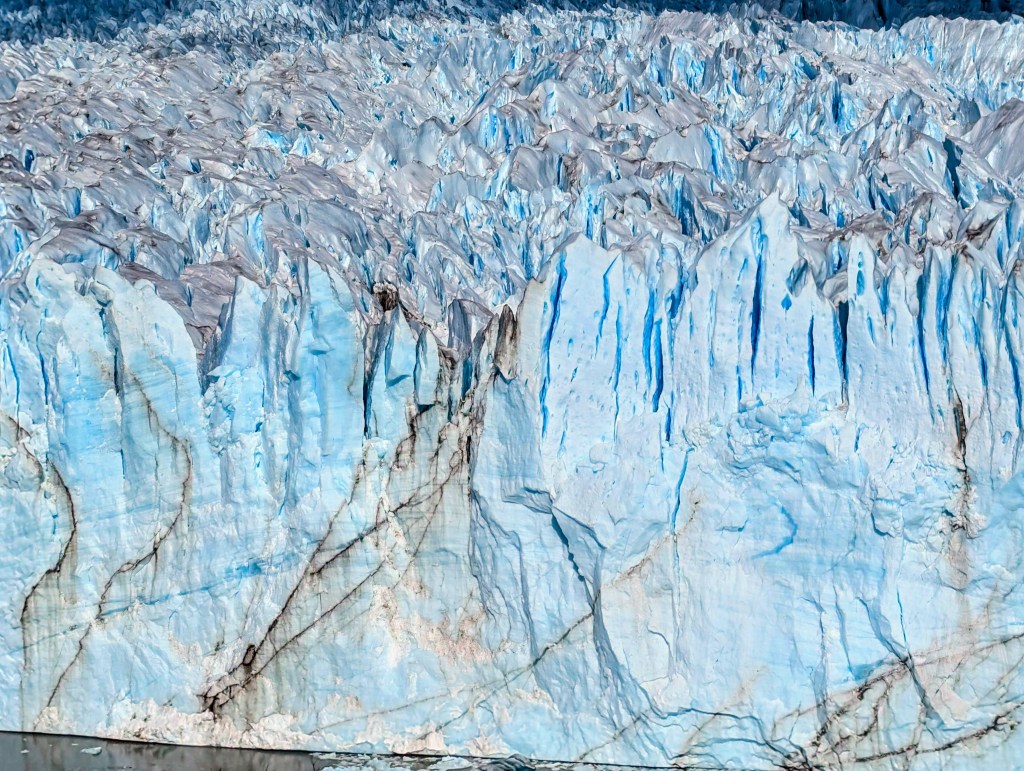

And finally we approached our destination for the day: the Perito Moreno Glacier. We got out for our first glimpse.

As we drove closer to the Perito Moreno Glacier Nadia explained that the Parques Nacionales Glaciares was founded in 1937 to protect the border with Chile, preserve the Southern Patagonian Ice Field (the huge mother of all the glaciers) and its glaciers (the country’s main source of fresh water), and the sub-Antarctic forests. The park was not initially created for tourism. Finally we reached the top of the access to the Perito Moreno Glacier. We spent the next over two hours traveling the extensive walkways, viewing the glacier from all sides, and learning more about it.

Covering 97 square miles with a length of 19 miles, the Perito Moreno Glacier is the third largest in the park, but it is the most accessible.

The glacier’s top sits at and altitude of 950 feet; its bottom is at an altitude of 650 feet. It moves at a rate of 6-7.5 feet a day. It takes 500 years for the ice to reach from the top to the bottom.

The streaks seen on the face of the glacier are from sediment picked up as the glacier moves. The are called morenas.

As we had seen in in the Parque Tierra del Fuego, the trees here are of the same beach family, but there are two species here: one deciduous the other an evergreen. The former has leaves significantly larger than the latter. The deciduous trees are turning color almost two months early this year because they have been stressed by drought. Both can be seen below.

The park has provided a extensive boardwalk system from which to view the glacier.

The glacier does not float on the lake, it stretches down and sits on solid bedrock. At the front it extends down about 150 feet but laterally it extends down as far as 750 feet. Facing the glacier the south wall is to our left, the north to our right. The south wall has a height of about 120 feet from the surface of the channel; the north has a height of about 210 feet. Because it is mostly protected by the mountains, the front of the glacier has been mostly stable or even grows some years, so the locals like to brag that it is the only glacier in the world not receding. But in fact it has become thinner and shallower through the years, so it is in fact shrinking.

The glacier is named for Francisco Moreno who was born in Buenos Aires in 1852. Perito means expert. Moreno is considered a hero in Argentina because he made the maps which at the time played an important role in the border disputes with Chile. For his work he was given by the Argentinian government extensive lands near Lake Nahuel Huapi in northern Patagonia. He then donated those lands back creating the first national park.

Perito Francisco Moreno never actually reached this glacier which bears his name. He did reach and name Lago Argentina, Lago San Martin, and Cerro Fitz Roy.

We stood for a long time watching and listening to the glacier calving small chunks from above and huge chunks that detach from the base. The sound is a cracking sound combined with thunder. The current of the water hitting the glacier at the surface sounds like lapping waves.

Nadia pointed out the tuft in the tree which is called false mistletoe ans is parasitic but does little actual damage to the tree.

Nadia shared that although she comes daily, she is never bored as the glacier is forever changing taking on new and more beautiful forms even hourly.

At our closest point to the glacier we were about 600 feet away. From here one can appreciate the narrow space between the glacier and the rocks of our shore which connect the channels that flow from the south to the north. Between 1917, when observations first began and 2018, the most recent occurrence, that space has closed off several times. When that happens the Brazo Rico/Sur channel to the south becomes blocked and the water level rises as much as 75 feet in the past, 52 feet in the 2018 episode. The water erodes the surrounding land. Ultimately the pressure of the water creates tunnels in the glacier until the front collapses allowing the water to flow freely again.

F

We climbed back to the top, had a quick snack, then headed for our boat trip to visit the glacier from the water.

Along the way Nadia pointed out that the layering visible in the rocks is caused by the glacier both carving and depositing sediment as it moves over the bedrock.

We added even more layers to be able to stand out on the boat’s deck as we approached the glacier.

I do not have a lot more to add other than the views of the glacier were spectacular. We sailed toward the southern face.

The blue color is an optical illusion caused by the density of the packed ice squeezing the air out. Air on the surface of frozen water cause all of the light waves to bounce back giving a white appearance. But the densely packed glacier allows the red and yellow waves to absorb allowing only the blue to reflect.

Each angle provides a different but awesome picture.

The largest icebergs were detached from the base. Only 10% of any iceberg can be seen floating above the surface; the rest remains below.

The littler icebergs fell from the top of the front of the glacier. The grey color of the water is due to unsettled sediment.

The boat guides pulled a few small icebergs on board for us to see and feel.

From this vantage point one can see how narrow is the space between the front of the glacier and the opposite shore through which one channel flows into the other.

It had been a long day. By the time we returned to Hotel Blanca Patagonia, we were ready for an early dinner. We hiked down to the lake’s edge to dine in Parilla Rustica. There I tried the calafate sour made from the blueberries of the plant to which we had been introduced hours earlier.

While enjoying a delicious grilled dinner, we were entertained by an Argentinian Tango.

The next morning we again beat the sun.

We were picked up early and driven with fellow passengers for the day to Port Moreno on Lago Argentina, baptized by Francisco Moreno in 1875. We boarded the boat for Estancia Cristina.

We travelled across Lago Argentina through its narrowest portion known as Hell’s Gate due to the high cross winds.

As we sailed towards the glaciers, we headed out onto the front deck to take a look around. We started to see our first icebergs floating in the lake.

and our first large iceberg of the day.

Boy was it cold out there!

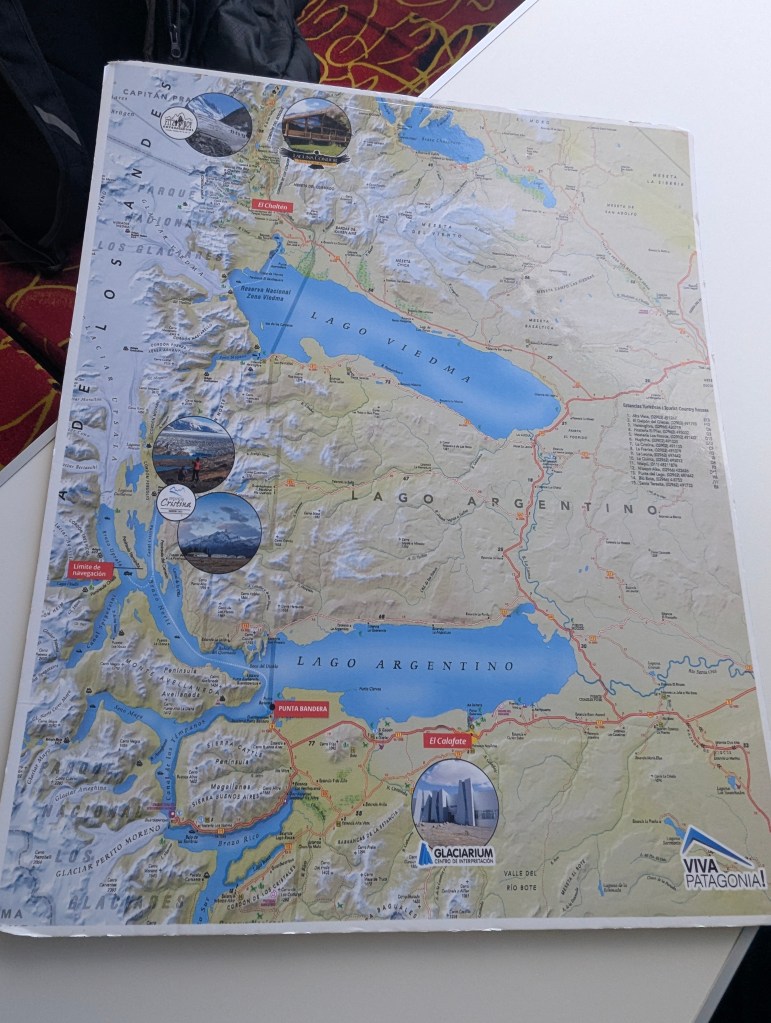

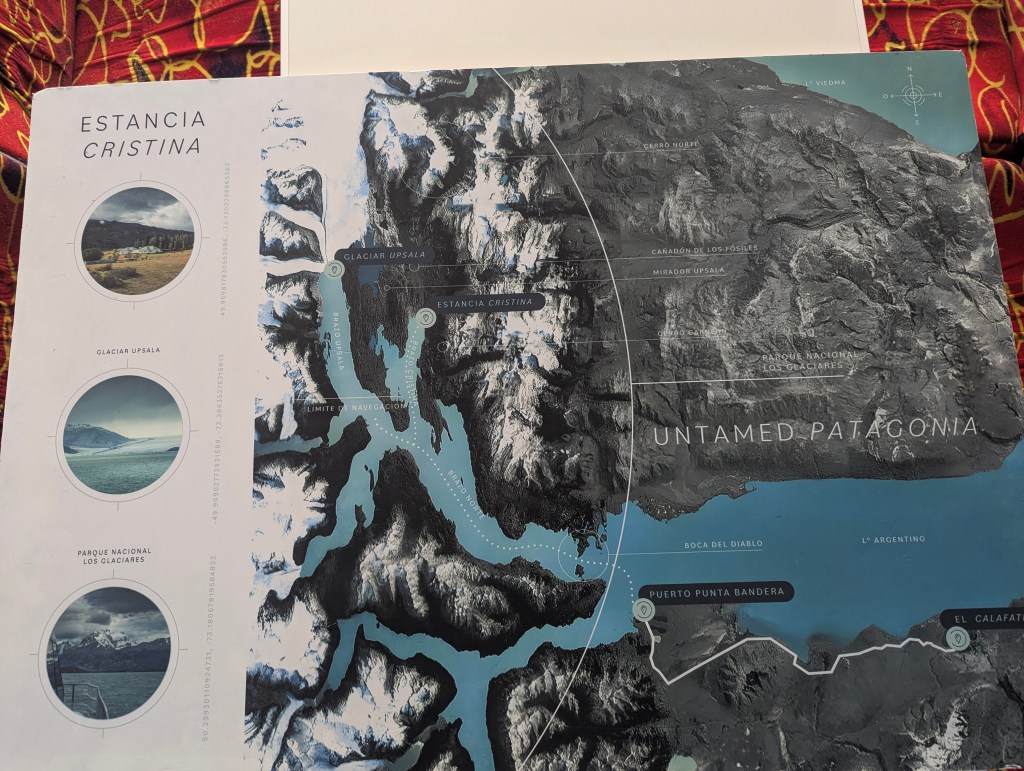

While we were headed toward the Upsala Glacier, I took a moment to study the maps. The map below shows the town of El Calafate Port Bondero where we boarded near the bottom. On the southwest corner of the map is Perito Moreno Glacier that we visited yesterday.

Zooming in, north of the Glaciar Perito Moreno are the channels we will enter today; the furthest north and west channel goes to the Upsala Glacier, the one next to it goes to Estancia Cristina, which we will visit. Notice on the map how far past the Glaciar Beriacchi (the top left corner of the map) the Glaciar Upsala extends. This is an eight year old map.

The next map is a two-year-old map which shows the Glaciar Upsala only as far as the Glaciar Beriacchi.

The reality of today is that the Glaciar Upsala has receded beyond the base of Glaciar Beriacchi; they are no longer connected. The other glacier seen between the two is Glaciar Cono, which so far is still connected to Glaciar Upsala although there appears to be a border between them. And finally, the glaciers have come into view from the boat. The fronts of the three above referenced glaciers are visible, but whether or not they are connected is not discernible from this view.

or even this one

We sailed near a large iceberg.

We had reached the closest we were allowed to the glacier fronts.

But as the boat slowed and circled the icebergs while everyone snapped photos, it started to warm up a bit.

The icebergs are truly beautiful.

This picture gives an idea of scale; the bergs are huge!

Eric took a gorgeous panoramic view of the mountains reflected on the lake.

We then sailed up the adjoining channel to Estancia Cristina.

We boarded the largest 4×4 I have ever seen, so high it required a ladder to enter from the rear.

We drove for about 50 minutes toward the glacier on a road hand made by 40 men using pick axes and shovels, very bumpy. Along the way we saw large hillsides covered with fallen dead trees. We were told that over 80 years ago while trying to clear land for sheep and cattle grazing, a fire got out of control and decimated much of the forrest. As we had seen in other forests in Patagonia, decomposition happens very slowly here.

When the national park took over the land from the ranchers, they were asked to remove their animals. It was too expensive to relocate all of them, so many of the sheep and cattle were left behind. The assumption was that the animals would not last the winter. That was true for the sheep, which mostly became prey to the local pumas. But the cattle survived and now exist in the wild.

These are the eighth generation of wild cattle. They are purportedly aggressive toward tourists, but we only admired them through the windows of our 4×4.

We diembarked our 4×4 and began our trek toward the Upsala Glacier.

The landscape here is mostly that of Moraine terrain, a landscape created by glaciers and made of a variety of materials, including silt, boulders, sand, and clay. The resulting sediment is not conducive to vegetation. The smooth rocks were polished by the glaciers “glacier polish” or “pulimento glacier” in Spanish.

The striations are cut as the glaciers pass over the rocks.

Millions of years ago this area was under the sea. Fossils can still be found in the area.

And so we started our hike toward the Upsala Glacier.

We stopped to see a shelter maintained by the Ice Institute. It is for scientists or park rangers who, for whatever reason, need to spend the night in the area. When it was built in 1950, it was a 15 minute walk to the edge of the glacier. Today it is about an 8 hour walk.

The shelter is always open and availbale.

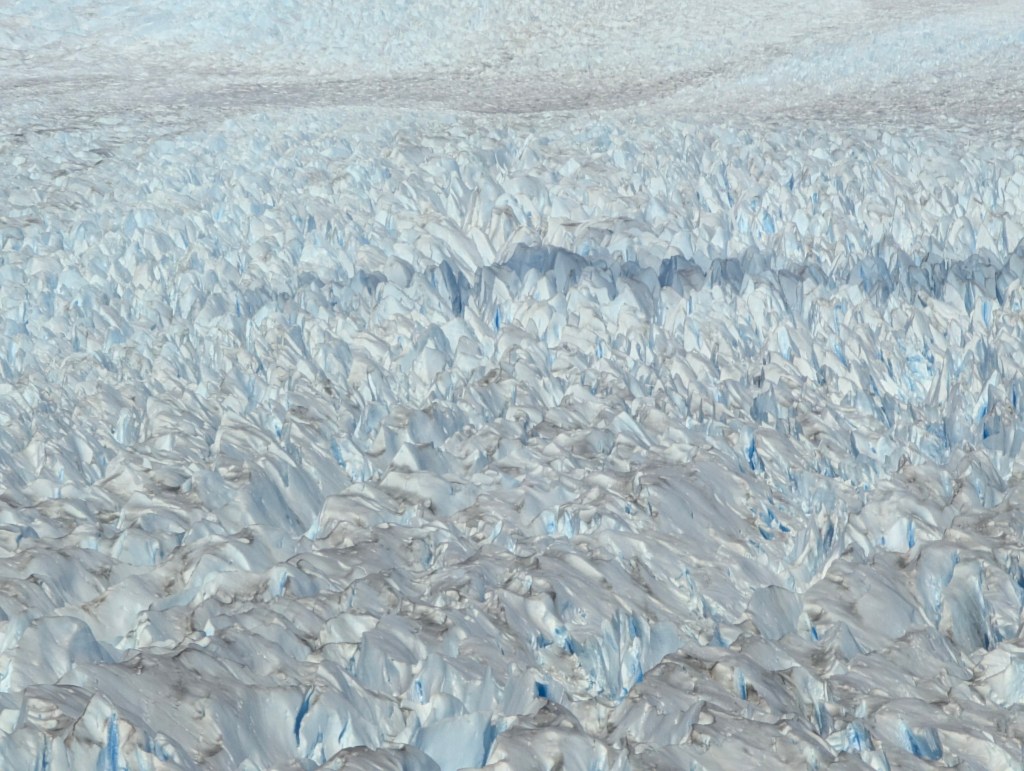

As we hiked we got our first glimpse of the Upsala Glaciar.

We continued along the path and were able to see the fronts of the Beriacchi Glacier on the left and the Cono Glacier on the right with the very front of the Upsala Glacier on the far right.

And finally the front of the Upsala Glacier as it is joined by the Cono Glacier at its front edge.

The Upsala Glacier at 197 feet long with a surface area of over 330 square miles, it is 3 times larger than the Perito Morena Glacier. It is the second largest in South America. Unlike the Perito Moreno Glacier, the Upsala Glacier is floating on the lake.

The glacier is named for Upsala, a Swedish university located 44-miles from the capital, Stockholm. It was the first university to sponsor glaciological studies in Los Glaciares National Park.

Glaciers must always be moving. For their formation and sustenance, they require rain, snow, cold, and wind.

Glaciers that are not valley glaciers are called hanging glaciers. In Argentina, they are named for the mountains upon which they sit like the one on North Mountain, seen below, the highest peak in the area at almost 9,000 feet.

We could not get enough of the beauty of this special place.

And oh the colors were spectacular, or as they say in Argentina, “buonisimo!”

especially the colors in the rocks due to all the minerals contained therein.

We reluctantly made our way back to our 4×4 and the return bumpy and windy 50 minute trip back to Estancia Cristina.

There a delicious lunch of local specialties including squash soup, guanoco meatballs, lamb, grilled veggies, and fried parmesan cheese was waiting for us in the restaurant.

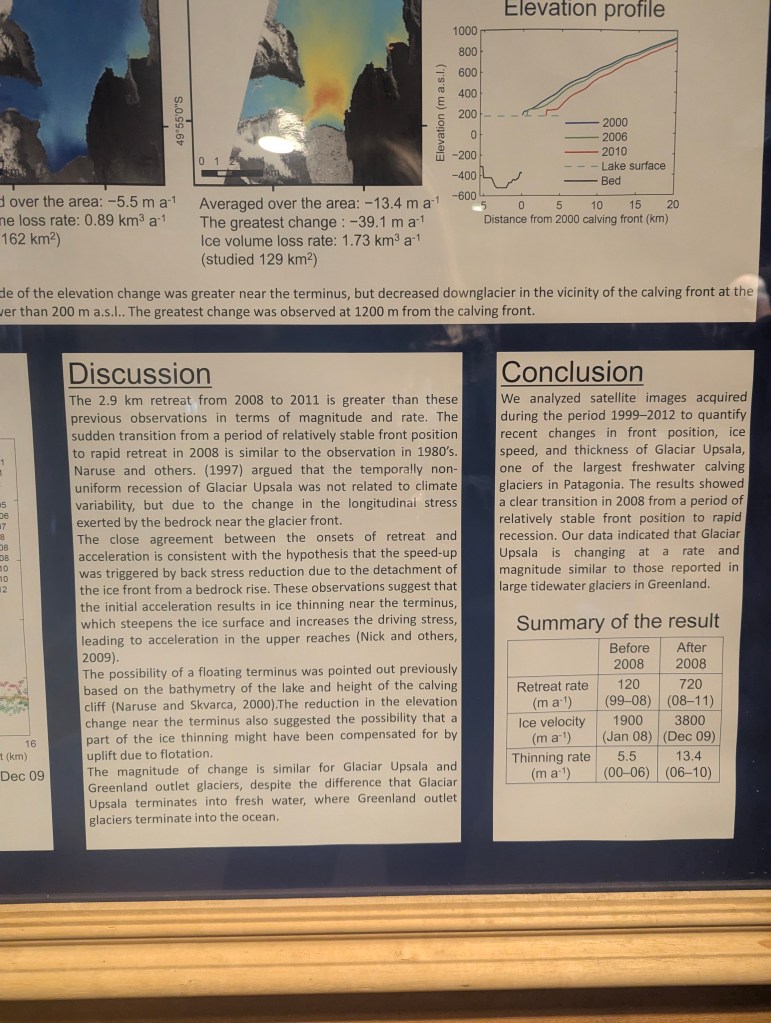

When asked about the human effect of global warming vs the natural evolution of the planet warming, our guide carefully responded with “my government and the park service require me to say that the data is uncertain.” To determine the rate of decrease in size of the world’s glaciers, one must study both the accumulation zone as well as the front of the glacier. The “accumulation zone” refers to the upper part of a glacier where more snow accumulates than melts, typically at higher altitudes, while the “front of a glacier” is the very edge or terminus of the glacier, which is the lowest point where the ice reaches and is where most melting and calving occurs, marking the boundary between the glacier and the surrounding land. The following data that appeared on a wall chart in the restaurant supports the effect of “human related global warming” on the shrinking of the glaciers. This is important because the Southern Patagonian Ice Field is the third largest source of global fresh water behind Antarctica and Greenland.

After lunch we were given a tour of the ranch and its museum. In Patagonia estancias have a historical as well as economic significance. In the mid nineteenth century the decision was made to boost an agricultural big-scale production as the base for the country’s flourishing economy. Lands in remote areas appropriated from the native peoples were given as farms to mostly European immigrants. The Homestead Act of 1884 established an amount of 20,000 hectares (about 50,000 acres) to be given each family for wool production. As long as the taxes were paid, after a period of 30 years the family would own the property. Percival Masters was moored in Punta Arenas, Chile in 1900 when he and his then girlfriend Jessie heard of the possibility of gold in Patagonia. They made their way here only to find pyrite, “fools gold.” Upon hearing of the possibility of land ownership for wool production, they moved to this western part of Santa Cruz. They arrived in 1914 with children Herbert age 4 and Cristina 9 and lived in a tent for the first year then built this small home, which took 9 months to build.

The inside is this one small room.

This is the original heater.

In 1919 they moved into this larger home which they surrounded with trees and shrubs to block the persistent strong winds. Only the front of the house now is the original. Originally the name of the farm was Estancia Masters, but is was changed to Estancia Cristina to honor their daughter after she passed away in 1924 from pneumonia.

Inside the museum we can see what their kitchen looked like.

Sheep were brought to Patagonia from Buenos Aires, where they had been introduced from Islas Molvinas, in large herds traveling for many miles and for many months, sometimes up to two years. In 1900 there were 74 million sheep in Patagonia. Today there are about 12 million.

Initially the shearing was done by hand, which took about 10-15 minutes.

But with the invention of the motorized shaver, the shearing process was reduced to 3-5 minutes.

The wool needed to make it to market. A ship was built by the family in 1962 using a blueprint from the Popular Mechanics Magazine.

In 1937 the farm became part of the national park, so the family could not fulfill the term of their ownership. Instead they received a yearly renewable permit to farm the land as long as a member of the family remained on the land. In 1953 the Institute of Ice was formed to study and preserve the territory. Herbert became a guide for the institute in the 1950s. He lived his life on the farm with his parents who both lived well into their 90s. In 1966 Herbert brought Janet Hermingston to the farm to help with his aging parents. Janet fell in love with the farm and remained after Percival and Jessie passed away. At the age of 82 Herbert married Janet so she would become family and could remain on the farm after he passed away which he did in 1984 of lung cancer, having been a lifelong smoker. Prior to his death Herbert and Janet had worked the farm together, but after he died in 1984 the wool production ceased completely. In the 1950s the area started to become an attraction for climbers and scientists. In 1985 Janet began a Bed and Breakfast and changed the permit to one for tourism, but at that time she had to get rid of all of the animals. Janet worked with some of those more famous climbers including Pedro and Jorge Skvarca, Eric Shipton, and Cosimo Ferrari to create the Estancia Cristina of today: a place for tourists, climbers, and travelers. Janet passed away in 1997. Estancia Cristina is now owned by a corporation that has been granted rights to continue the tourism operations within the confines of the national park. For those staying at the ranch, horseback riding is an option.

And finally it was time to say goodbye.

and reboard the boat back to El Calafate.

And all of that was just our first week in Argentina!