Our visit to Argentina’s wine countries started in Mendoza, home to more than 800 wineries. The region around Greater Mendoza is the largest wine-producing area in South America. As such, Mendoza is one of the eleven Great Wine Capitals. For the first time we had a connecting flight. When the bad weather delayed our flight, we were concerned about the connection in Cordoba. It turns out our same plane was flying to Mendoza, so no worries, phew. We landed in Mendoza airport late in the evening after a long day of delays and were picked up by Max. While driving Max explained a bit about Mendoza, the capital city of the province. With a population of over a million, it is the fourth largest city in Argentina. Before the 1560s the area was populated by tribes known as the Huarpes and Puelches. The Huarpes devised a system of irrigation that was later developed by the Spanish. This allowed for an increase in population that might not have otherwise occurred. There are less than 8 inches of rain a year. The water to the city comes via the Mendoza River from the snow melt in the Andes. The system is still evident today in the wide acequias (trenches), which run along all city streets, watering the approximately 100,000 trees that line every street in Mendoza. This system had been used for irrigation for vineyards and other agriculture produce in the area until recently; a new automated drip irrigation system is currently in use for agriculture. After about a 20 minute drive from the airport which bypassed the city proper, we arrived at our new home-away: Verde Oliva.

There they took pity on our late arrival and offered to bring us dinner on our own little terrace, what luxury.

In the morning, after a delicious breakfast, Max, our driver, plus our guide Francisco picked us up and explained that not only did we arrive in the middle of harvest, but today was the first day of the harvest festival (as well as being International Women’s Day). To celebrate the harvest even McDonald’s offered a meal that came complete with a glass of wine. We headed for our first winery, Bodega Benegas in the Luján de Cuyo region of Mendoza. The Luján de Cuyo region is known as The Cradle of Malbec. Surrounded by gentle hills and overlooked By America’s highest mountains, Lujan de Cuyo is known for its country houses, tree lined streets, fine restaurants, Malbec vineyards, olives and world renowned wineries. Francisco pointed out the adobe structure, common to the area.

The winery guided tour started in the courtyard.

The building is an historical landmark of Mendoza, built in 1901 by Agustin Álvarez, former Governor of Mendoza. Much of it was destroyed during a 1985 earthquake along with about 70% of the homes at the time. Federico Benegas Lynch bought it in 1999, and made a 5 year restoration, keeping its original design, including the adobe walls and concrete wine vats, but adding state-of-the-art technology. She explained that the family continues to use the buildings as a home. We entered their patrician style living and dining rooms.

The dining table was made from a single very tall tree imported from Brazil.

Federico Benegas Lynch also has a passion for ponchos, each made by hand in traditional colors. which he collects and displays. Beneath are family photos.

In keeping the winery part of the family, each wine is named for one of his children.

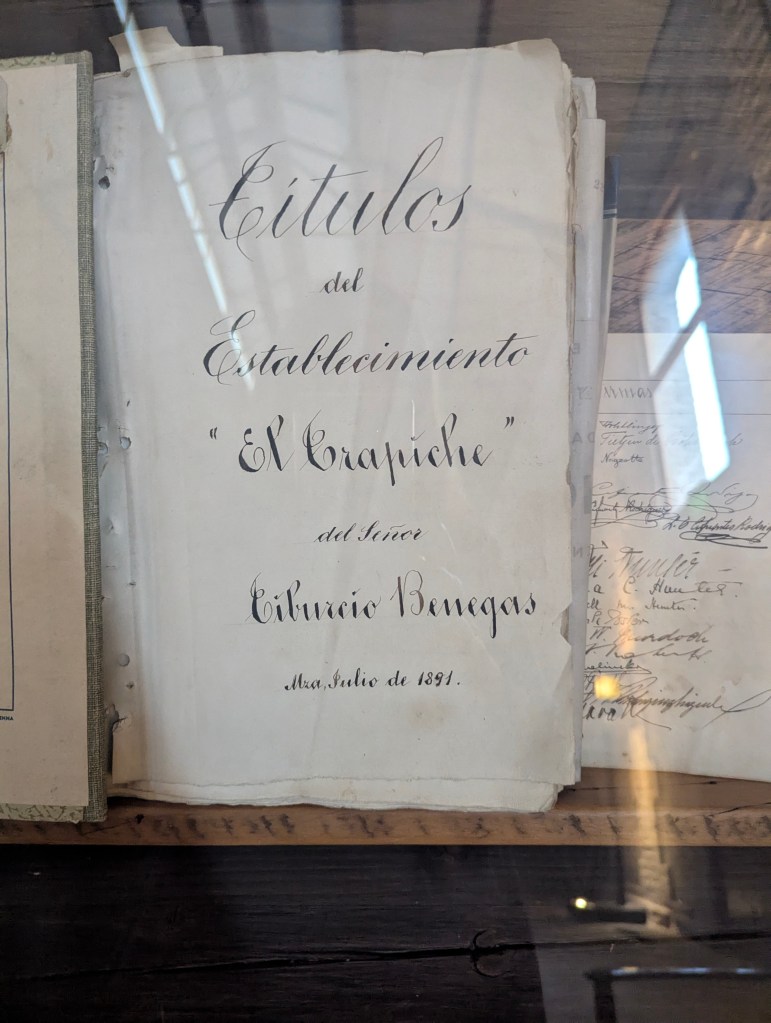

Federico Benegas Lynch, fourth generation of winemakers, grew up accompanying his father in the production of wines in El Trapiche. After the dissolution of the company during the economic crisis of the 70s, he went to live in Buenos Aires. He subsequently studied viticulture in France and discovered a family connection with the Lynches there. His passion for Mendoza and for wine made him return in search of recovering the family legacy. That is how in 1999 he had the opportunity to buy Finca Libertad, an old vineyard planted by his great-grandfather Don Tiburcio, who had been one of the founders of wine production in Mendoza in 1883. The first harvest of this new winery, Bendegas, was in 2001. On display here is his grandfather’s diary.

We then entered the winery itself. This is harvest season and grapes are coming into the facility. The first process is the sorting of the grapes, which is done by hand. Only the best 20% are chosen, the remaining 80% are exported, to maintain the status of boutique winery. The chosen ones then go to a de-stemmer.

The grapes are then placed into a crusher, which works by inflating a balloon. As mentioned above, during the restoration, the original concrete tanks were maintained for fermentation. The one shown below in the far right even has the original wooden door. The hoses are pumps for mixing during the maceration process.

With over 800 wineries to choose from, there is competition for tourists. Bendegas prides itself in its history. They have a little museum containing everything from the original de-stemmer,

to the crusher,

to the original pump, which had to be cranked by hand,

and the original delivery wagon. In years past the average Mendozan consumed much more wine than today, even the children. The wine would get delivered from this large barrel with the customers providing their own 5 liter jug for filling.

The loads of grapes once harvested were so heavy, they had to be pulled by oxen rather than horses.

The wine cellar is 60 feet underground with walls of 6 feet thick to maintain the constant temperature of 63 degrees F. The French oak barrels are used only four times.

The wine is sent down to them via a hole into the room with the concrete tanks above.

Once bottled, the wines are stored in the cellars in rooms that were originally tanks themselves.

as evident by the hole above

and the outlet below

And now it was time for our tasting. Although we have visited many wineries in our days together, we always manage to pick up some new tidbit of info each time. Here we learned that the depth of the indentation at the bottom of the bottle as well as the thickness of the glass are indicators of how long the wine is expected to age in the bottle; the former to allow sedimentation, the latter for preservation.

The wines in Mendoza use French varieties and do not require grafting onto American roots because due to the low humidity in the valley, they are not susceptible to phylloxera. Malbec is the star of the Mendoza region. The valley’s hot days and cold nights make for very thick-skinned grapes giving the Malbec wine its deep rich color. The soil is rocky, requiring deep roots, which gives the wine its mineral taste. But the star of the Benegas winery is the cabernet franc produced from the wineries oldest vines aged 120 years. The Benegas Lynch, of which only 5,000 bottles are produced a year, can last 20-40 years.

Along the way to the next winery, Francisco told us that the region’s agriculture is not only wine but also corn, garlic, peaches, plums, pistachios, and of course, olive oil. Many of the wineries also produce their own olive oil. Also, although rain is infrequent, there can be severe hail storms as well as dust storms brought in by the sonda winds. A storm lasting only a few minutes can wipe out an entire season’s harvest. Many of the plants are protected by netting which could be observed in many of the groves we passed.

When we reached our next winery, we were greeted first by a 100 year-old olive tree.

Winery number two for us was Tempus Alba in the neighboring Maipú region of Mendoza. Maipu is the first viticultural area in Argentina, chosen by the first European immigrants to continue their most beloved family tradition: wine making.

While we waited a few minutes for our tour to begin, Francisco (left) and Max (right) posed for my blog so I could make them famous, little do they know how tiny my readership is, lol.

Tempus Alba winery was founded by two Italian families that wanted to create the “true” Argentinian Malbec. In 2007 they studied 364 genetic varieties and chose three plants as their “mother” plants. They use a micropropagation system with the buds in jars of agar. The buds are then adapted to their environment for planting. One bud may produce 5-10 plants. A three year-old vine will produce grapes, but they are not used for wine making until the plant is five.

They have planted only about 0.5 square miles of grape vines surrounded by their 100 year-old olive trees. Seventy-five percent of their grapes are exported.

The vines are wrapped in netting to protect them from hail.

The grapes are harvested by hand and collected in a basket.

Once selected, de-stemmed, for the red wines, the crushed grapes are left in contact with the skins and seeds for 25-30 days, a process called maceration, then filtered. The solid waste is use later for fertilizer. (For white wines, the skin and seeds are discarded immediately. For rosé, they are left for a much shorter period of time.) During maceration cold water is run through a jacket in the outer wall of the tank to minimize fermentation, which would mean malic acid transforming into lactic acid.

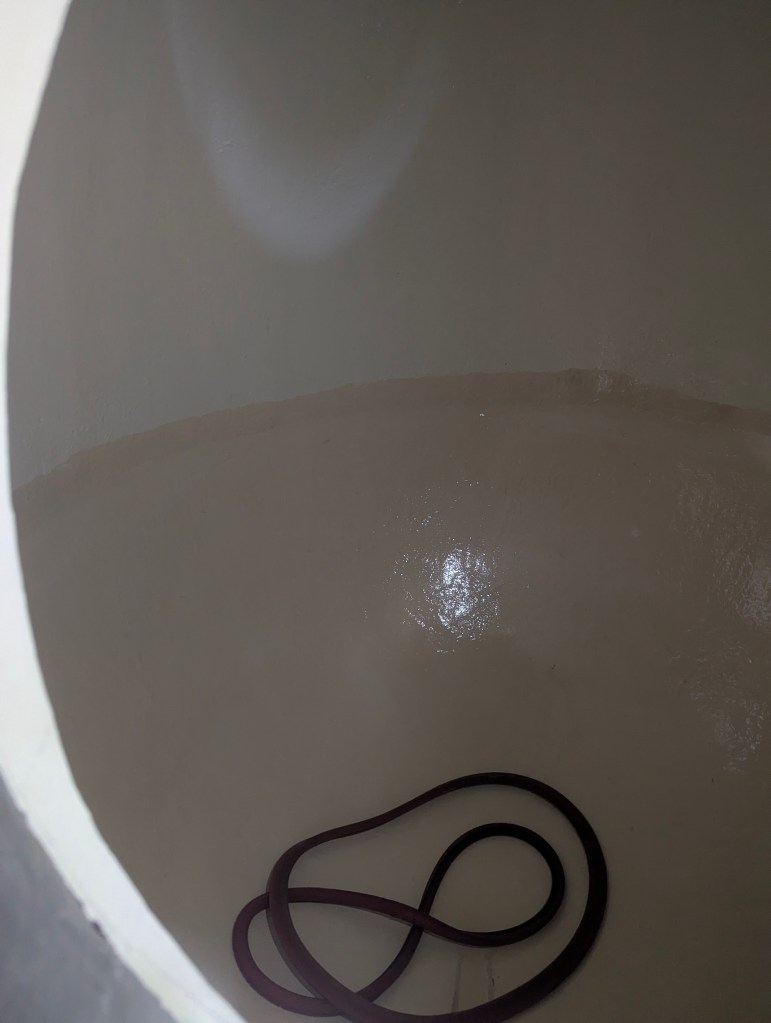

Maceration usually takes place in a steel tank, but sometimes an egg is used. Because of the shape, the egg does not require a pump to allow the mixing of the contents.

Also, the egg is coated on the inside with an epoxy paint which prevents the wine from picking up flavors from the vessel. Interestingly, at Benegas earlier they had praised the benefit of their concrete tanks because they do add mineral flavors to the wine. Each wine maker has his/her preferences.

After filtration, the wines are then rested 6-10 months to allow the sediments to settle before transferring them to barrels for fermentation. Tempus Alba also only use their oak barrels four times, but they use both French and American oak depending on the desired result. The former are more closed-pore than the latter. The more open the pores, the more surface exposed, the the bigger and bolder the flavors.

Once discarded, used barrels are repurposed as furniture.

We went onto the deck for our tasting. Here we learned that the closer the “legs” of the wine on the glass as it is swirled, the higher the alcohol content.

Also paying tribute to their children and grandchildren, the winemakers include the children’s fingerprints on their labels. The winemakers find that today wines using blends of varieties have become more popular that the traditional single varietal wines. The Vero (True) wine is their signature wine produced from their propagated plants. We tried all three. below.

As we left, I had to take a picture of the entrance door handle, which I loved.

At our third and final stop of the day, Restaurante Santa Julia (serving wines of Zuccardi), a tour was not included; lunch was the focus. Our first course was served outside,

their white from the Argentinian torrontés grapes,

with homemade empanadas.

Back inside the restaurant we enjoyed a course of breads and their own olive oils

and a red

served with fresh tomatoes, mustard greens with fried sweet potato chips accompanying asado. Asado is an Argentinian tradition of slow grilling over a fire several meats together, often goat, lamb, and sausage, as served here.

The next course included another red

served with filet mignon, smoked eggplant covered in palenta, and a green salad with pistachio clusters.

At this point we were so stuffed we needed a walk before dessert. We strolled out under the Malbec vines covered in a different hail protection netting.

We noted the elevated drip irrigation system.

We also noted these, which we were to find out later are metal barrels with wood beneath for a fire for warmth should the temperature drop to a cold level that would endanger the plants.

The bougainvillea was in full bloom. What a beautiful day.

Finally we returned for our dessert wine served with choices of cheeses from cows and sheep, several fruit jams, and flan with dulce de latte (cream caramel). No wonder Argentinians go for a siesta after lunch! We were done for the day.

The next day was Sunday, and we enjoyed the respite. We debated going into Mendoza City for a look around, but decided to enjoy the day relaxing by the pool and enjoying our resort instead.

Eric sent his drone up for some pictures of the property.

In the morning we were back to wine tasting. We set out for Valle de Uco, known for its high-altitude vines and microclimate ideal for viticulture, as well as its stunning backdrop of the high Andes. This region features some of Argentina’s most acclaimed wineries producing Malbec, Merlot, Pinot Noir and Semillon. Uco Valley is too cold for olive trees, but it is the capital of walnut trees in the country. Our first stop was Masi Winery, an organic winery.

Masi can be found at the foot of the Tupungato volcano in mineral rich soil. It is owned and operated by a 7th generation family of Italian winemakers who have been reproducing their family’s techniques in the Uco Valley for 26 years. They have about 270 acres in production, a mid-sized operation. Most of the wine produce, as much as 90%, is exported to Canada.

First we were shown some of the herbs grown like penca.

The leaf of the jarilla plant is very good for a sick stomach.

The emblematic grapes of the Venetian regions, Corvina and Pinot Grigio, co-exist happily at Masi Tupungato with the traditional Argentinian grapes, Malbec (from France) and Torrontés (uniquely Argentinian), in a unique and extraordinary natural paradise.

They were in the process of harvesting while we were visiting, all picked by hand. What is unique to Masi in Argentina is they have brought their Italian method of drying grapes: appassimento. Red grapes only are left to dry for 2 weeks here in Argentina (2 months in humid Northern Italy). During the appassimento process, the grapes will dry and concentrate, reducing water by 20%, while also reducing acidity.

The cane used, from the stalks of sugar cane plants, is similar to bamboo from Brazil.

Only once the grapes have dried are the stems then removed and the grapes pressed.

For maceration Masi uses 60 steel tanks from Italy, which are all automatic and do not require pumping for mixing.

The jacket within for temperature control can be seen.

Another winemaking practice imported from the Valpolicella region of Italy is use of the 600-litre (about 160 gallons) French oak barrel for aging, for 2-18 months, depending on the grape.

The wine ages in the steel tank for 2 years after first aging in the French oak barrels. The largest tank is 100,000 liters (about 26,500 gallons)!

We got to taste the wine straight from a tank.

The wines produced are mostly mixtures like the Paso blanco, which is 60% pinot and 40% torrontes, 12% alcohol.

and the Corbec, which is the star of Masi and aged 18 months in the oak barrels, is 70% Corvina and 30% Malbec, 15% alcohol.

We got a peak at the mixing lab on our way out.

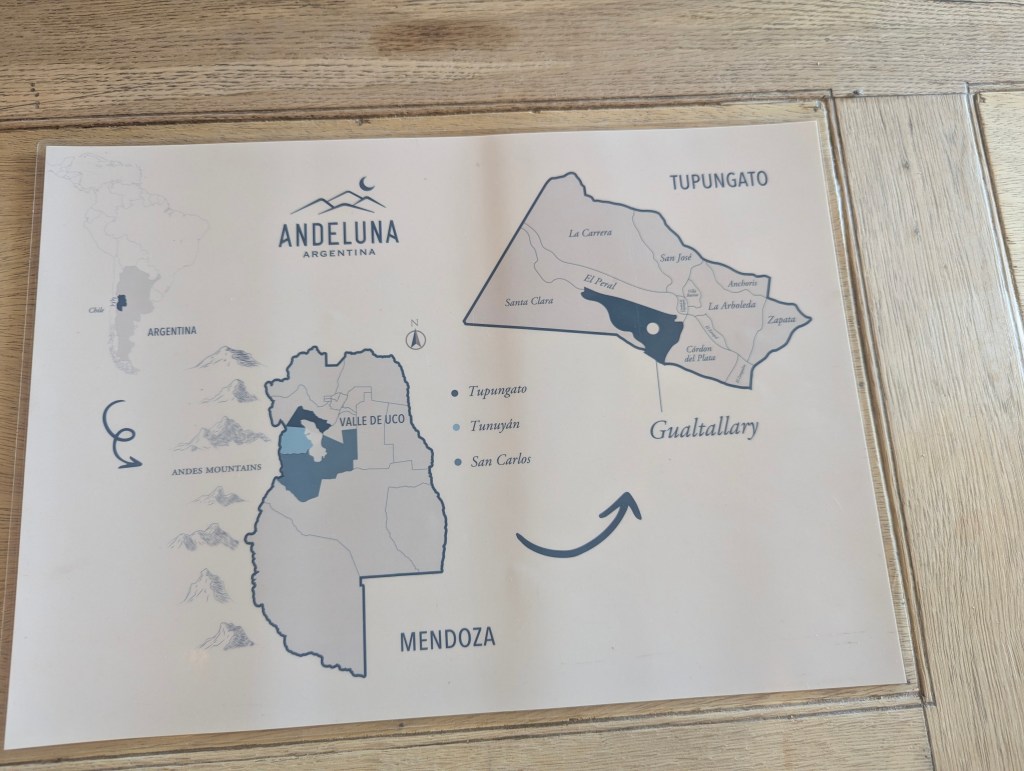

Our next winery in the Uco Valley, at an elevation of 4265 feet, was Andeluna, named for the mountains from which they get their water and the moon above.

The vines were first planted in 1997, but the winery was founded in 2003 by Ward Lay (of Pepsico/Lays). In 2013 it was taken over by a Brazilian oil family.

Here too the Topungato Volcano stands above the vineyards. At nearly 200 acres of planted grapes, it is a midsized winery.

There are three important ingredients that make the final aroma of the wine: the grape, the soil, and the wood used for the barrels. This vineyard sits at the base of the volcano and gets most of its fertile soil from there,

but it also has alluvial soils that were part of the sea bottom 100 million years ago. Four distinct layers of soil can be seen in the calicata below, all of which enhance the flavors of the wines.

Here we also learned how to distinguish the grape by its leaf:a caberntet savignon has 5 pointy segments; a cabernet franc has 5 rounded segments, and a Malbec has only three segments. The leaves below belong to a cabernet savignon. It takes 5-6 plants for 1 bottle of wine.

The high altitude makes for warm days and cool nights with as much as a 50-60 degree difference in temperature, which makes for thick skinned grapes, which enhances their flavor. The grapes here are harvested by machine. Unlike in the Maipú and Lujan de Cuyo regions, the plants here are grafted onto American roots.

Pods are used on grapevines to disrupt mating by Lobesia botrans, a common moth pest in vineyards. These pods release female pheromones, which confuse male moths, preventing them from finding and mating with females. A single moth could consume an entire plant.

Drip irrigation is used to maintain proper water levels.

The stainless steel tanks for maceration are sterile. The process takes two weeks.

The clarification process of removing the stems and seeds uses a decanter then animal enzymes are added for fermentation; for vegan wines carbon fillers are used. Andaluna uses a variety of barrels (all French oak) and eggs to ferment the wine depending on the grape and the desired effect. Interestingly, Argentina does not regulate what wines can be considered a reserve; it is up to the individual winemaker to determine.

After a tasting of the Andeluna wines, we headed to Gaia restaurant for lunch.

The view from our table was spectacular.

Again, the Tupungato Volcano was visible.

There we also had a view of Cerro El Plata, the highest peak of the Cordón del Plata, which is a subrange of the Andes. The mountain is located 37 miles west of Mendoza.

At Gaia we enjoyed another multi-coarse meal with accompanying wines starting with fresh tomatoes,

and smoked eggplant

followed by meat

and finally panacotta with sorbet.

Clearly the eating and drinking in Argentina are well worth the trip.