We flew from Salta City to Puerto Iguazú, home of the famous falls. We were met at the airport by a driver and our guide for the next 2 days: Matias. Matias welcomed us to Puerto Iguazú with its population of 45,000. He told us that Iguazú means big waters in Guarani, a living Indigenous South American language, primarily spoken in Paraguay, where it is a national language alongside Spanish, and is an official language in this part of Brazil. The climate here is subtropical with rainfall and humidity all year and only occasional frost. The Misiones Province is so named because of the Jesuits who came to convert the locals, the Guaraní, who were living here in harmony with nature. Each mission was like a small city. On the Portuguese side, the locals were made into slaves. On the Spanish side those locals who joined the mission were protected from soldiers. On the Spanish side there were 18 missions; they had a Bible printed in Guaraní. Misiones Province is now notable for its waterfalls as well as its rich red soil and plentiful vegetation. At the time of the Jesuits’ arrival, yerba mate grew wild in the area. The Guaranís drank it through a bamboo “straw” from a gourd with a hole in it. The Jesuits tried to forbid the drinking of mate because they thought it promoted laziness. But when forbidding the drink was unsuccessful, they instead started production. Today 95% of Argentina’s yerba mate is grown here; it is called green gold.

They left us at the Iguazú Jungle Lodge with information of where to explore and dine with the remainder of our day.

We hiked up to the northernmost region of town to this little park.

A harpist played while the sun set.

This location, “Triple Frontera” (Triple Frontier), is where the Iguazú River joins the Paraná River; three countries come together; Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay. The Friendship Bridge seen across the river connects Brazil on the right to Paraguay on the left in this picture.

All three flags are flown.

We passed a small artisinal market in San Martin Plaza.

We had a delicious Argentinian tomahawk steak at La Rueda (The Wheel) Restaurant before heading back for the night.

In the morning as we drove toward the falls, Matias explained that the park was created in 1934 to protect the border area as well as the environment. Iguazú Falls’ water source, is the Iguazú River, which originates in the Serra do Mar mountains in the Brazilian state of Paraná. The river flows for about 820 miles before plunging over a series of cliffs and plunging 220 feet, creating the spectacular Iguazú Falls, the largest waterfall system in the world, on the border of Argentina and Brazil. Along the way are many tributaries and hydroelectric dams, all of which can effect the water flow at any time. Matias emphasized that all of the water is from rainfall, not melting glaciers or snow caps in the mountains.

Matias also informed us that due to deforestation, only 7% of the original Atlantic Rain Forest remains, most of which is now in this area, which is now a protected green corridor to protect endangered species such as jaguars (Guarani for “kills in one leap”), pumas, ocelots, wild pigs, tapirs, and more. Coaties are common here, as we will see soon. This is the most biodiverse area in Argentina with many species of birds, mammals, amphibians, reptiles, numerous insects and butterflies.

We had finally reached the park. While Matias procured our tickets, we studied the map. While the Brazilian side of the falls is known for its panoramic beauty, the Argentinean side offers a more close-up look at the falls from above and below with its winding upper and lower trails.

As we embarked on the upper trail first, Matias pointed out the tall, skinny cecropia tree in whose hollow trunk ants live. Birds eat the fruits; the leaves are brewed to treat upper respiratory infections.

The first falls we reached were Dos Hermanas (Two Sisters).

And around the corner we came to our first sighting of the majority of the falls, a formation which originated over 150 million years ago.

Next we approached Salta Chico.

We could appreciate Brazil across the way

and how very far the falls wrap around. The total distance on the top is 1.7 miles across with 70% in Argentina, 30% in Brazil.

Next we came to Bossetti Falls named for the engineer and explorer Carlos Bossetti, a member of a 1882 German expedition that studied the region and built some of the first walkways.

Matias explained to us that after several years of visiting the falls almost daily, he now gets excited over uncommon things, usually found amongst the fauna. On this day he became excited at the rare, in the region, presence of a pato real or “royal duck,” discernible by the green on his back.

Next we came to a pair of falls named Adam and Eve, so named because while the rangers were choosing names for the falls, a couple was seen bathing and swimming naked beneath them.

From above Salto Adán here we could see an original, abandoned, walkway below.

Next came Salto Bernabé Méndez falls, named after Bernabé Méndez, a park ranger killed by poachers in 1968 while protecting the park.

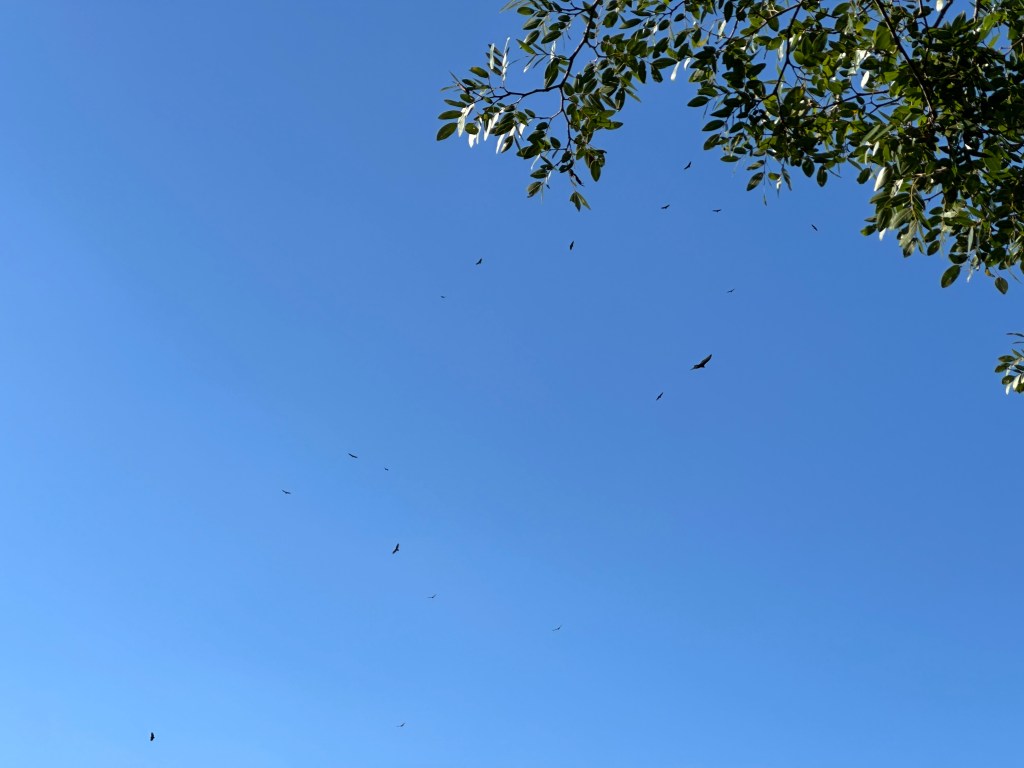

Matias pointed out the many vultures flying about.

Next we came to Salto Mbiguá.

Eric was fascinated by a huge spiderweb. Matias told us the nephila spider, one of the largest, spins a web so strong it can be used as fishing line.

Next we came to the second largest of the falls: San Martín. San Martín was an intellectual who promoted revolution in Argentina. Every town we have visited has had a prominent San Martín street and/or plaza; every province a San Martín city, and here, a San Martín Falls.

Here was a tree full of vultures.

As we hiked toward the lower trail, we passed a vulture on a rock.

It happens that the vulture was picking a dead fish up out of the river, an experience new to Matias. We watched for a while until the vulture was successful.

At the base of the trailhead we came to a rest stop. Here Matias chuckled as he told us that so many people have fed the wildlife, especially the coatis, the humans are now ironically forced to eat inside of cages to protect them from the wildlife.

We embarked from the bottom of the lower trail.

The first falls we encountered on the lower trail was the Salto Nuñez, named for Álvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, the Spanish explorer credited with the first European discovery of the falls in 1541.

We enjoyed walking along the bottom glimpsing falls in the distance.

From this lower vantage point we could see both the Argentinean side to the right as well as the Brazilian side to the left with San Martín island, on which the vultures sleep, in the middle.

Matias inadvertently dropped his water bottle over the fence while posing for this pic and had to (illegally) hop onto the other side for its retrieval.

With most of the falls in view, Matias explained that the total number of falls, somewhere in the neighborhood of 275, differs at any given time depending on the amount of rainfall, which has currently been slightly above average. There are times when the falls we are seeing now, immediately to the left of Salto San Martín, are not there. When the rainfall has been heavy, some of the falls converge and flooding can occur. He showed us pictures taken at times of two floods: the most recents in 2014 and 2023, and of the drought of 1978.

From the lower trail we got to see from below some of the falls we had seen from above. First was Salto Chico

then Salto Dos Hermanas

Matias pointed out a late-blooming ginger lily.

As we headed to the last leg of the Argentinean side of our journey, Matias explained to us that back in the 1970s, this area of the park was an airport. As tourism grew and the number of visitors increased, the airport was moved out of town and structures were erected within the park for dining and lodging. It was in this area we found our first coatis, a mammal in the raccoon family.

and owls in the trees

and a grey cracker butterfly.

We caught the train out to the Salto Garganta del Diablo (Devil’s Throat Falls). The trainline opened in 2001. Prior to its opening, tourists had to hike the distance.

Alighting from the train we were greeted by a plush crested jay.

We joined the trailhead out to the Salto Garganta del Diablo.

As we traversed the trail, a Cramer’s eighty-eight butterfly landed on Eric’s cap.

Matias informed us that this is the third walkway constructed to the Salto Garganta del Diablo (Devil’s Throat Falls). This one opened in 2001, same year as the train and tourist center.

The first walkway was washed away in the flood of 1982, the second in the flood of 1993. This one had parts washed away in the October, 2023 flood. and has been rebuilt four times in total in the 24 years since it opened. As we walked over the river, we could see remnants of the older walkways.

and parts washed away in floods.

On the river we saw a blue heron.

In the river we saw giant catfish.

As we neared the falls were were impressed with the number of people there.

We got close enough for our first glimpse of Salto Garganta del Diablo.

Finally we edged our way onto the viewing platform.

Words cannot describe the roaring sound of the falls

as well as the welcome coolness of the misty waters.

Of course a selfie was necessary.

We could not drag ourselves away, so we just kept snapping more pics.

Here at the top of the falls the river is wide and shallow. The color of the water changes based on the volume of rainfall, which has been greatly affected by deforestation. After joining the Paraná River below at the Triple Frontera, together they flow to Buenos Aires where they spill into the estuary Rio de la Plata and then into the Atlantic Ocean.

A few last pics of Salto Garganta del Diablo

and we headed back.

This time an Agathina Emperor butterfly landed on Matias’ vest. I have been in butterfly gardens with less impressive numbers and varieties of butterflies than seen here.

Back at the Jungle Lodge, spent from all the hiking, we lounged at the pool before dining in the Jungle Restaurant.

The next day was time for the Brazilian side of the falls. As we waited in a fairly long line for the border crossing, Matias filled us in on some of the history of the border between the two countries. Right now the border crossing into Brazil is much longer than in the past because every day goods, including gasoline and groceries, are much less expensive in Brazil after a significant period of inflation in Argentina. Due to large government debt, in December, 2001, after about 20 years, the Argentinian peso was unpegged to the US dollar. The thought at the time was that allowing the market to determine the exchange rate would radically improve competitiveness and eliminate the then current account deficit along with the need to borrow money to finance it which would hopefully stimulate the economy, which was suffering at the time from large unemployment numbers. This led ultimately to several years of runaway inflation, which Miele was elected to control in 2023. Since his election prices have stabilized, but continue to be higher than in Brazil. This has not always been the case. In times past gasoline was so cheap in Argentina, Brazilians would cross over the border to buy it and then sell it illegally in Brazil. Even with overall prices high in Argentina now, Brazilians and Paraguayans still cross into Argentina to buy wine.

Matias also pointed out to us the Itaipu hydroelectric dam on the border between Brazil and Paraguay which, built in the 1970s and opened in 1984, is now the second greatest producer of electricity in the world, only surpassed by one in China. It has 20 generators, 10 in each country. There is a second dam further down the river that generates power for Argentina.

Finally we made it across the border and entered the Brazilian park. Matias explained that because the Argentinian side had been cleared for an airport, the trees on the Brazilian side are much older and larger with levels of vegetation. Here there are Palm trees under canopies. Heart of Palm, for example, needs more shade than is typical in the subtropical jungle of Argentina. We soon got our first glimpse of the falls from the Brazilian side.

From here is a better river view

and a good look at most of the falls at once.

Matias loved to have us pose for pics.

From here we can also see the full 200 foot height of the falls and appreciate the two distinct levels.

a closer view of the different levels is below.

We came upon a crowd of people, some of whom were feeding the coaties, which Matias promptly and firmly reminded them was not allowed. It is no surprise why the humans now have to sit in cages to enjoy a meal.

The are pretty aggressive animals and, in my opinion, somewhere between cute and ugly.

We continued along the path admiring the falls from every vantage point. The conglomeration of falls in the main section is called Salto Rivadavia.

Here the vultures overhead seemed even closer.

Sightseeing boats go right up to and under the falls, drenching all of those aboard. Unfortunately, due to our loss of a day due to the cancelled flight, we were headed to the airport immediately following this excursion leaving no time for a boat ride. Not sure we would have done it even if we had the time.

A panorama, despite the distortion, shows the full expanse of the 1.7 miles of the falls. The full falls is called the Cataratas Falls.

We started to approach the end of the falls.

We headed toward the viewing platform already packed with tourists.

Once on the platform we could again feel the mist as it settled over us.

To the left is a tourist center with more viewing platforms at the top. The falls seen in the picture below, to the very left, are the only falls that cannot be seen from the Argentinian side.

The many smaller falls can be appreciated.

Far out onto the platform one feels the power of the water rushing by. Approximately 320,000 gallons spill over the falls every second.

One last photo op at the very tip of the viewing platform, up close to Salto Garganta del Diablo (Devil’s Throat Falls),

We did not wait for the elevator and started the ascent to the top.

Along the path Eric found another huge spider web, this one with its huge spider as well as its lunch caught in the web.

From this vantage point we have a side view of the fall not seen from Argentina.

We reached the very top.

Looking back on the viewing platform we could see a rainbow formed in the mist above the people below.

We asked about the large hanging bundles in the palm trees and were told they are birds’ nests.

Frederico Engel lived in and around the Iguaçu Falls (Portuguese spelling) during the early part of the 20th century. He was of a family of German immigrants who had lived in the south of Brazil since 1863. He was a pioneer in conservation efforts, keen to preserve the natural beauty of the falls.

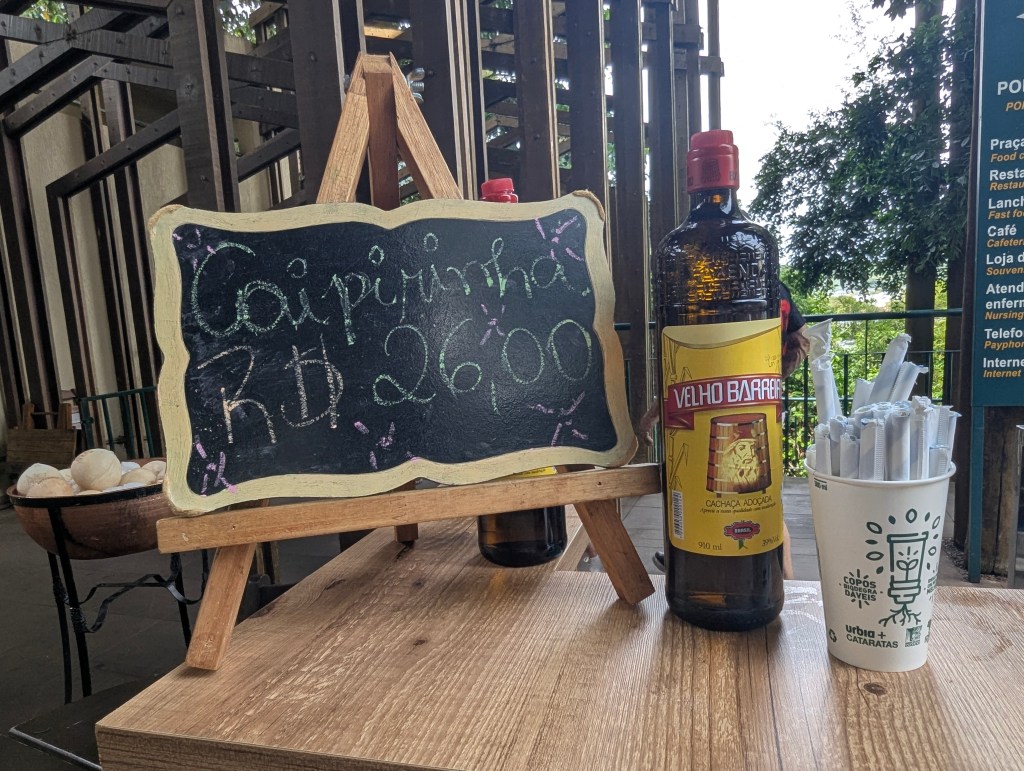

The caipirinha is Brazil’s national cocktail, a potent and refreshing drink made by mixing fresh lime wedges with sugar, then adding cachaça, a Brazilian spirit distilled from sugarcane, and ice. The traditional method extracts the lime’s juice and essential oils for a bright, earthy, and citrusy flavor that captures the essence of Brazil’s culture. Of course we had to try one.

While trying the national drink we had to try the national street snack: coxinha, a deep-fried croquette made from dough and a creamy shredded chicken filling, often flavored with broth and vegetables like onion and garlic. Shaped like a teardrop or drumstick, the coxinha is first coated in flour, then egg, and finally breadcrumbs before being deep-fried to a crisp, golden brown exterior.

We flew to Buenos Aires and checked into our hotel in the Palermo neighborhood, which was full of restaurants from which to choose for dinner. In the morning we were met by Laura for our tour of the city. She first told us that while the city of Buenos Aires has a population of about 3 million, the greater Buenos Aires metropolitan area includes about 16 million people, over a third of the population of the entire country. As we drove along Avenida del Libertador (Avenue of the Liberator), Laura explained that most of the European style buildings seen were built between 1880 and 1930. The southern part of the city is the oldest, but during the pandemic of 1880 most wealthy Europeans moved north.

On Avenida del Libertador we passed The Monument to the Carta Magna and Four Regions of Argentina aka the Monument of the Spanish. The monument was a donation by the Spanish community in celebration of the centennial of the Revolución de Mayo of 1810 (which marked the formal beginning of Argentina’s independence from Spain). It is made of Carrara marble and bronze. The foundation stone was laid in 1910 but it was not completed and inaugurated until 1927.

Our first stop was a statue of Eva Perón. María Eva Duarte de Perón, better known as Eva Perón or by the nickname Evita, wife of Argentine President Juan Perón, was an Argentine politician, activist, actress, and philanthropist who served as First Lady of Argentina from June 1946 until her death at home in July 1952. She died childless at the young age of 33 from cervical cancer. The statue is on the site of what was the home in which she lived and died. The statue is in a park where the presidents used to reside. (Since 1955 the presidents now live in Olivo, which previously had been their summer home.) She is depicted as running away from the pain of her cancer leaving her blanket behind. It was unveiled in 1999. An inscription at the base of the statue reads, “She knew how to dignify women, protect childhood and shelter old age, giving up all honors”. The small pile of bricks next to the statue are from the original house which burned down, from which she had escaped with her life.

Next we stopped in the Recoleta neighborhood. As we headed toward the basilica we passed a huge rubber tree (ficus) planted by monks in the Gran Gomero in Plaza Juan XXII.

An artist created the sculpture Atlas, a representation of the mythological titan, to support one of the tree’s massive, heavy branches. The statue symbolizes the strength and longevity of the tree, which is considered one of the city’s oldest and most iconic landmarks.

The Basilica of Our Lady of the Pillar, was built as part of the Franciscan monastery, completed in 1732. It is the second-oldest church in Buenos Aires, and had served as a parish church following the expulsion of the Franciscans in 1821. Now it is a cultural center.

The architecture is simple

but the internal decor is Baroque.

A picture composed of tiles hanging just outside the basilica shows what the city looked like in 1794. The river was closer than it is today; the land was later reclaimed for ports.

In 1822 monks donated land for a cemetery when their order was disbanded, and the garden of the convent was converted into the first public cemetery in Buenos Aires. As we entered the Recoleta Cemetery, we were immediately struck by how different this is to any cemetery we had previously visited.

For one, it is so large with so many mausoleums (almost 5,000 in 5.5 square blocks), it is organized along named streets.

At first they were simple.

But later became more elaborate.

Bodies are placed in a sealed zinc coffin which is then placed within a wood coffin, which is just for decoration. Some mausoleums are apartment style for the whole family.

Some mausoleums are very thin.

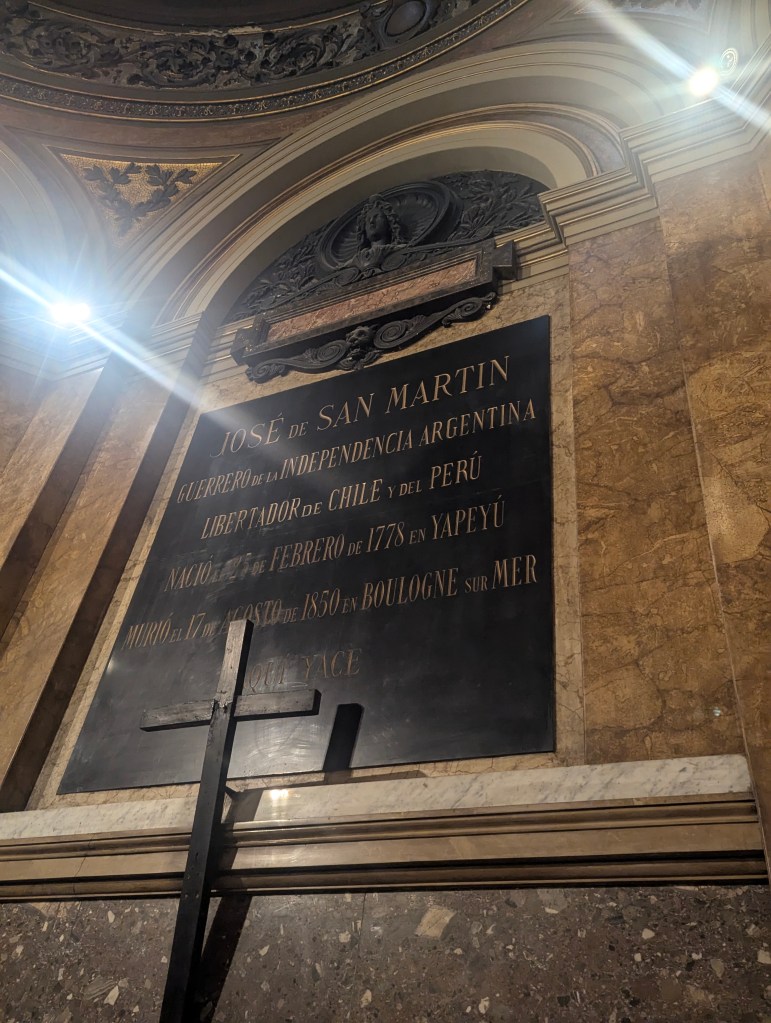

In 1823, one year after the cemetery opened, San Martin’s wife died of tuberculosis and was buried here. San Martin himself died in France, but ultimately his body was brought back to Argentina in 1980; he is laid to rest in Buenos Aires Metropolitan Cathedral, which we were to visit later. Originally San Martin’s parents were buried here by his wife, but they were later moved to Yapeyú, the province in which he was born.

William Brown (1777-1857) was the founder of the navy and was of Irish descent; his monument is green.

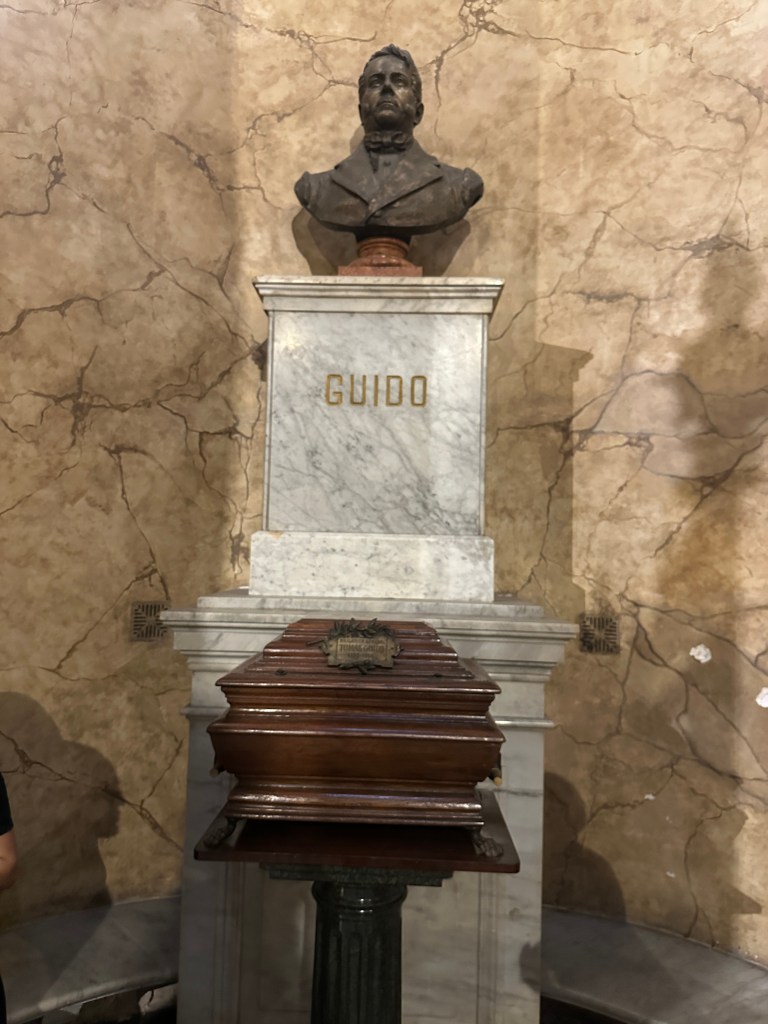

Tomás Guido (1788-1866) was a friend of San Martin and a general in the Argentine War of Independence. Together they had crossed the Andes Mountains; his mausoleum is made of rocks from the Andes. He was originally buried here but his mortal remains were moved next to those of San Martin in 1988 on the hundredth anniversary of his birth.

The cemetery filled in 2003. All of the plots are family owned and have a contract with the government for 80 years. After 80 years if no one pays the government for the contract, the government can take the plot back and sell it. Therefore, there continues to be new ones added all the time. This is one of the newest.

A peak through the glass window reveals the interior.

Often there is a downstairs chamber for other family members; note the stairwell to the right.

Bartolomé Mitre (1821-1906), the sixth president of Argentina, was the first constitutional president. He was interred in his family mausoleum and the government maintains it.

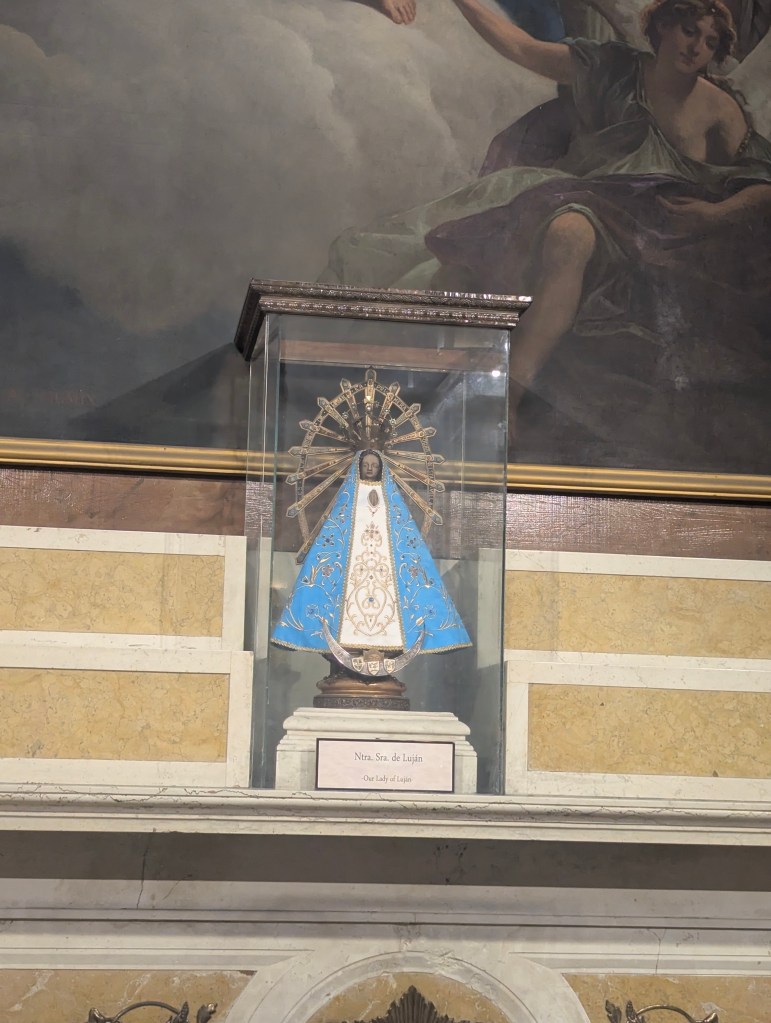

The patron saint of Argentina is Our Lady of Luján (Nuestra Señora de Luján), also known as the Virgin of Luján, often adorns mausoleums. (more on her later) Seen below to the right, she is the Madonna with the wide triangular-shaped veil.

And of course, Eva Perón (1919-1952) has a place in the Duarte family crypt in the Recoleta Cemetery, a significant landmark and popular tourist attraction. After Evita’s death in 1952, her body was embalmed, placed in a glass coffin, and set to be housed in a monument. However, following a military coup that ousted her husband, Juan Perón, in 1955, her body was secretly removed. It was hidden for years and eventually buried in a cemetery in Milan, Italy, under a false name. Her body was returned to Argentina in 1974 with her husband Juan Perón when he returned from exile. She was interred five meters underground in the heavily fortified crypt, owned by her brother Senator Juan Duarte, to prevent further theft or desecration. The tomb is a place of pilgrimage for many, especially for the thousands of people who visit each year, many of whom bring flowers or ribbons.

My favorite story of all was that of a Liliana Crociati de Szaszak, a young newlywed who died in an avalanche in Innsbruck, Austria, in 1970. Her father, a hairdresser, built her a Gothic-revival crypt featuring a life-size bronze statue of Liliana in her wedding dress. After her beloved dog, Sabú, died, a statue of him was added, with Liliana’s bronze hand resting on his head. This was reportedly against cemetery rules, as pets are not typically buried there.

We drove back north along Avenida 9 de Julio (July 9th Avenue), believed to be the widest avenue in the world and a central thoroughfare, named after Argentina’s Independence Day. It has 22 lanes, 11 on each side, as well as a median totaling over 450 feet wide. The center lanes are for buses only. There is parking below ground. Along the way we passed three embassies and the Park Hyatt Hotel, all of which had been built between 1880 and 1930 as private homes.

We next visited The Catedral Metropolitana de la Santísima Trinidad (The Metropolitan Cathedral of the Most Holy Trinity), dedicated to the immaculate conception. It is the most important cathedral in Argentina. The building site was first committed to the church in 1580. The current cathedral building began in 1754, after the collapse of the second of the previous two churches on this site, and was finished in 1940. It now overlooks the Plaza de Mayo (May Plaza).

Inside we found a little chapel dedicated Nuestra Señora de Luján (Our Lady of Luján, sometimes referred to as The Virgin of Luján). The devotion to Our Lady of Luján began in 1630 when a Portuguese rancher from Brazil was transporting two clay statues of the Immaculate Conception. The oxen pulling the cart carrying the statues stopped moving near the Luján River. When one of the images was removed from the cart, the oxen resumed their journey, leading people to believe that the Virgin Mary wanted to be venerated there. A small chapel was built at the site, which eventually grew into the magnificent Basilica of Luján in the city of the same name. The Basilica is a major pilgrimage site, with millions of Catholics visiting annually, especially for the Feast Day of Our Lady of Luján on May 8th. Pope Pius XI formally declared Our Lady of Luján the patroness of Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay in 1930.

The Virgin of Luján is considered the spiritual heart of the nation, a symbol of unity, and a source of hope for the Argentine people. She is not only the patron saint of the country but also that for travelers. Public buses are adorned with her image.

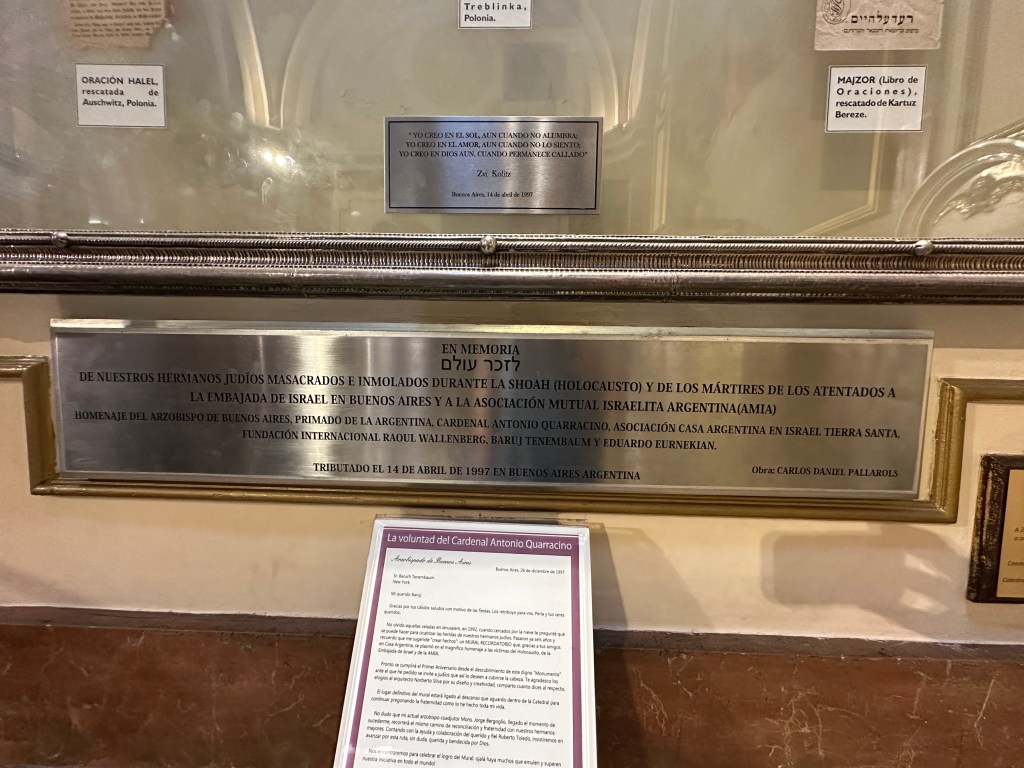

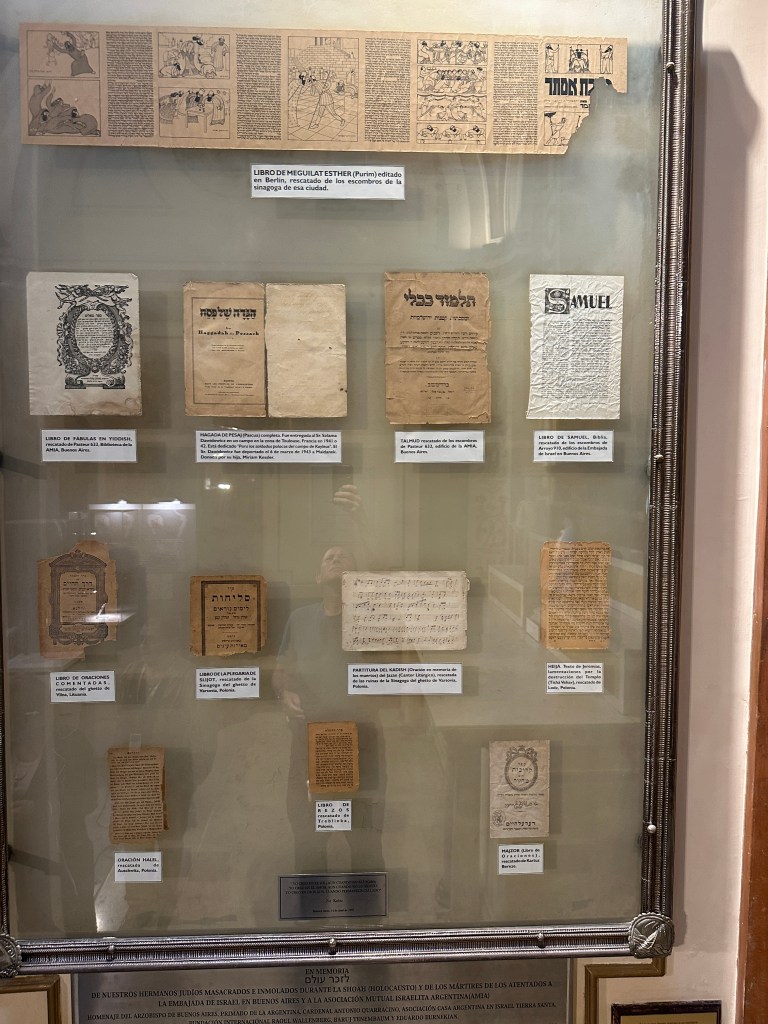

In the adjoining chapel of the cathedral is a Holocaust Memorial.

The floors of the cathedral were one of the last parts of the construction to be completed in 1940. They are composed of mosaic tiles.

There are impressive frescoes on the ceilings.

The high alter is flanked by the choir stalls.

An 1871 Walker organ has more than 3500 pipes. It was made in Germany with the finest materials available at that time. It is now played once a month.

Laura surprised us with her timing having coincided with the changing of the guards,

who are from the military and are there to protect the mausoleum of San Martin.

In the early 1800s Argentina passed a prohibition on wealthy families burying their loved ones in private chapels within cathedrals, which is why the Recoleta Cemetery was founded. An exception was made for their heroes. As we had learned throughout Argentina, José Francisco de San Martín y Matorras (1778-1850) was the hero of independence, nicknamed “the Liberator of Argentina, Chile and Peru.” In 1880 the remains of San Martin were brought from France and placed in a mausoleum shown above behind the guards. The mausoleum was designed in various shades of marble by a French artist.

There are less people in the way in the back of the tomb.

The black sarcophagus is guarded by three life-size female figures that represent three of the regions freed by the General:

Chile, represented by an anchor,

Peru, represented by the pick for the silver mines.

and Argentina, represented by broken chains which are symbolic of liberation achieved by the major battle of San Lorenzo.

The mausoleum also has the remains of Generals Juan Gregorio de las Heras (1780-1866), also a general in the War of Independence, and Tomás Guido, as mentioned previously.

After paying our respects to the leading founders of the country, we stepped out onto Plaza de Mayo (May Plaza), formed in 1884 as the hub of the city. The Pirámide de Mayo (May Pyramid), located at the hub of the plaza, is the oldest national monument in the city. Its construction was ordered in 1811 to celebrate the first anniversary of the May Revolution, a week-long series of events that took place from 18 to 25, May 1810. The monument is crowned by an allegory of Liberty.

From there we could see the office building of the current regime, the Casa Rosada (Red House), which was originally built as a fort, the government palace, and the customs building. The red symbolizes the blood shed during the War of Independence; the color was originally a mix of bull’s blood and lime, which protected the building from humidity.

Laura commented that the fencing seen in front of Casa Rosada is not typical and probably to hold back the expected crowds for the upcoming day’s potential protests. The Plaza de Mayo has traditionally been the focal point of political life in Buenos Aires. On 17, October 1945, mass demonstrations organized by trade unions forced the release of Juan Perón, who would go on to become president three times, from prison. During his tenure, the Peronist movement gathered every 17 October (Loyalty Day for Peronists) in the Plaza de Mayo to show their support for their leader. Many other presidents, both democratic and military, have also saluted people in the Plaza from the Casa Rosada’s balcony

The plaza, since 1977, is where the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo have congregated with signs and pictures of desparecidos, their children, who were subject to forced disappearance by the Argentine military in the Dirty War. People perceived to be supportive of subversive activities (that would include expressing left-wing ideas, or having any link with these people, however tenuous) would be illegally detained, subjected to abuse and torture, and finally murdered in secret. The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo took advantage of the symbolic importance of the Plaza to open the public’s eyes to what the military regime was doing. The mothers wore white headscarves during their silent marches to represent the nappies (diapers) of their missing children.

The Equestrian monument to General Manuel Belgrano (1770-1820) holding the flag of Argentina was dedicated on September 24, 1873, at an anniversary of the Battle of Tucumán. General Manuel Belgrano was an Argentine public servant, economist, lawyer, politician, journalist, and military leader. He took part in the Argentine Wars of Independence and designed what became the flag of Argentina.

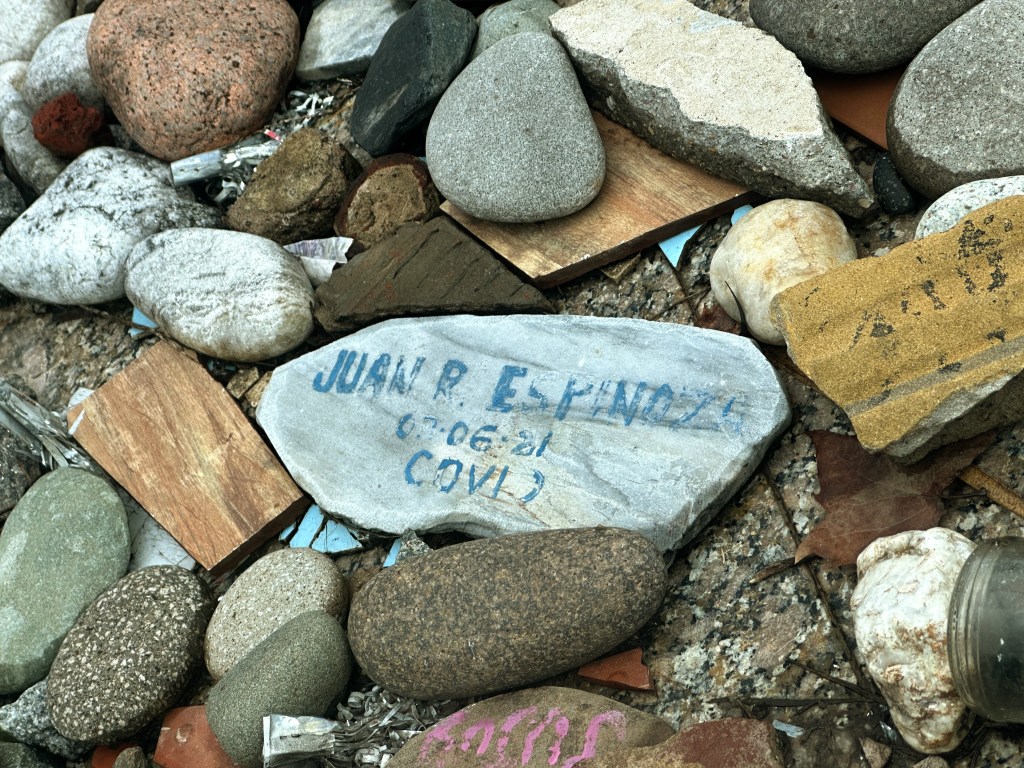

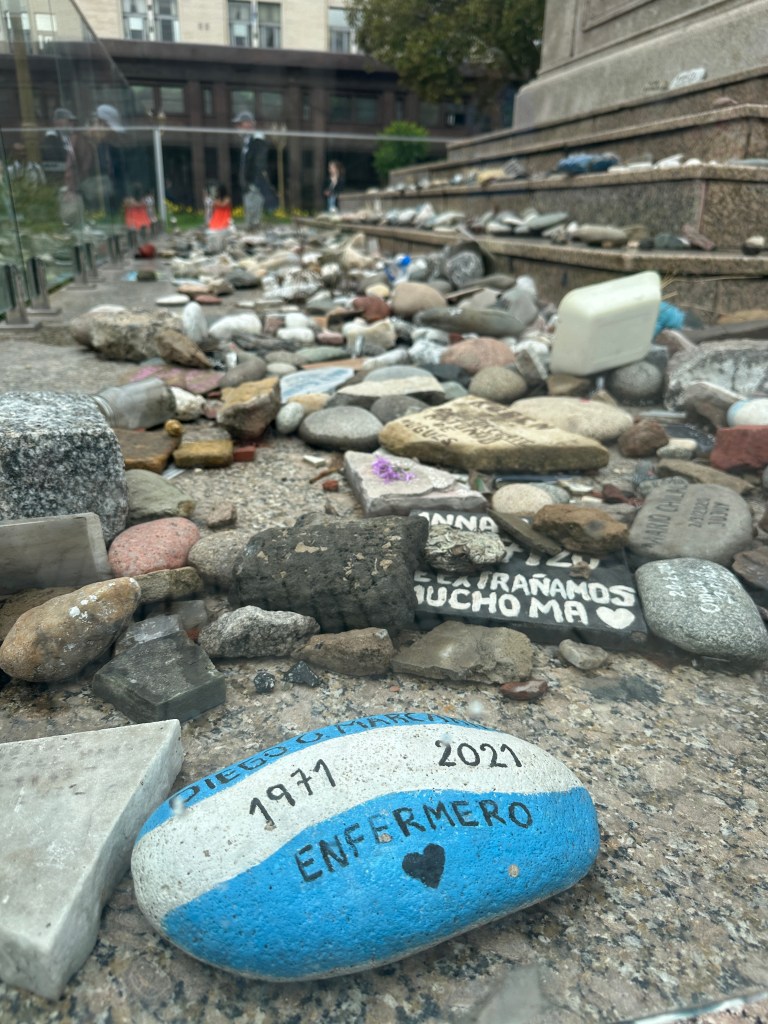

A closer look at the statue revealed stones thrown onto the base.

Laura explained that the painted rocks around the statue are from families of those lost to COVID-19 during the pandemic and a protest to the then president celebrating his wife’s birthday during lockdown.

Argentina suffered 300,000 deaths due to the virus.

Other buildings around Plaza de Mayo include: The Cabildo of Buenos Aires, a public building that was used as a seat of the town council during the colonial era and the government house of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata and a prison from 1608-1877. The Cabildo was declared a National Historic Monument in 1933 and was opened to public as a museum in 1938.

and the Bank of the Argentine Nation.

As we left Plaza de Mayo we passed the building of the Ministry of the Economy built in 1854.

Laura pointed out the still remaining bullet holes from the 16th, June 1955 attempted coup on Perón’s government.

Next we traveled down to the working class neighborhood of La Boca (The Mouth), located at the mouth of the River. We stopped by the football (soccer) stadium which has a 45,000 seat capacity.

Our driver and guide Laura support opposing teams: our driver, Boca Junior and Laura, River Plate. Legend has it that when picking the team colors, the captain of Boca Junior went to the port and the first ship he saw was flying a Swedish flag: yellow and blue.

The Boca Junior team has had some quite famous footballers through the years.

The La Boca neighborhood was the first port in the city. In 1536, the Spanish, led by Pedro de Mendoza arrived and founded the first settlement, named Nuestra Señora Santa María del Buen Aire (Our Lady of Saint Mary of Good Air) on the land that would centuries later become Parque Lezama (Lezama Park). This initial settlement was short-lived, however, and was abandoned by 1541 having been driven out by indigenous people. For decades Paraguay, with its riches in silver, became the center of the Spanish colonization; Argentina was re-found in 1580. The residents of La Boca neighborhood were often from Genoa and historically so poor that they painted their homes with whatever remnants of paint were leftover from ships. The colorful neighborhood now gets a fresh coat of paint yearly.

Through the years there have been may fires threatening this poor neighborhood which has built a longtime love and respect for the firefighters who protect them.

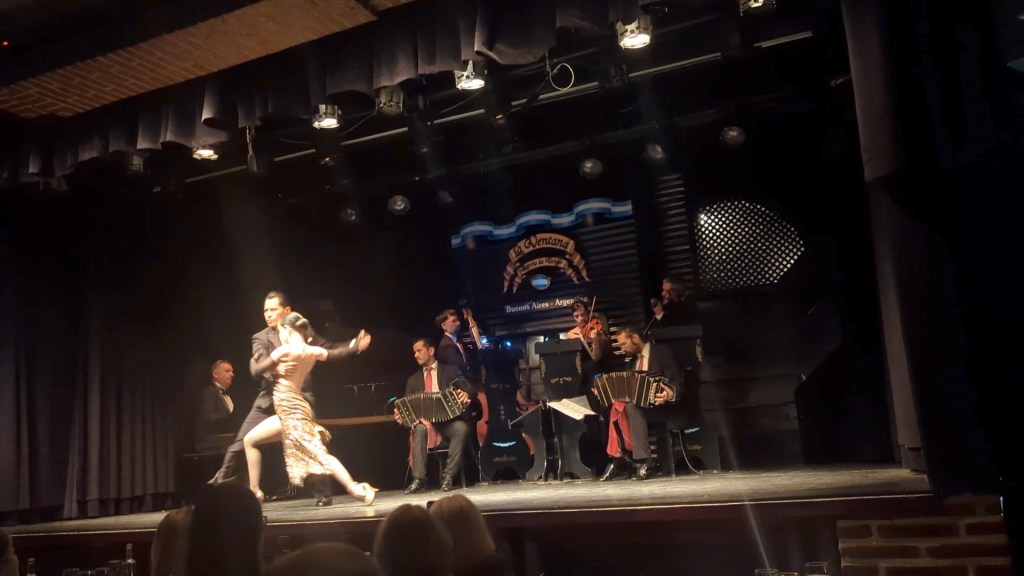

Influenced by a mix of rhythms of Africa and European music, tango was born in the late 19th century here in the brothels of the South of the city.

Initially shunned by the upper class, tango spread through dance halls and became a national symbol, reaching global popularity in the early 20th century before declining. It then experienced a resurgence in Argentina in the 1980s after becoming fashionable in France.

Caminito is a vibrant, colorful “museum street” and tourist attraction in the La Boca neighborhood.

Immortalized by the famous tango “Caminito,” the area is characterized by brightly painted tenements that house artists’ studios, souvenir shops, and bohemian bars, creating a unique tango atmosphere.

Santos Vega was a mythical Argentine gaucho, and invincible payador (type of minstrel who competed in singing competitions), who was only defeated by theDevil himself.

Slavery in Argentina began in the 16th century, and the port neighborhood of La Boca, located in Buenos Aires at the mouth of the Riachuelo river, was a major entry point for enslaved Africans. Many of the slaves ultimately settled here enriching the culture of this working class neighborhood.

Of course the patron saint of the city, The Virgin of Luján, is represented here.

Laura treated us to some alfajores, chocolate sandwhich cookies, from famous Cachafaz Caminito.

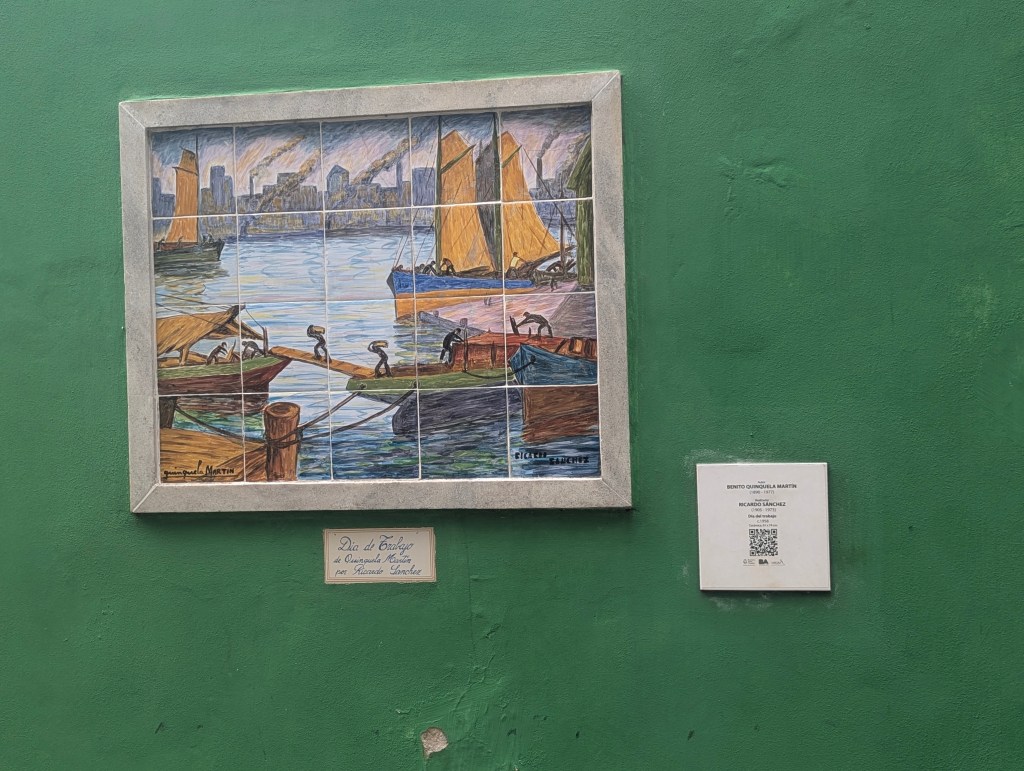

While waiting for the driver to come back for us, we wandered about the port for a bit. Laura pointed out the statue of Benito Quinquela Martin (1890-1977) whose paintings of port scenes show the activity, vigor and roughness of the daily life in the port of La Boca. He then donated his profits back to the port community.

His donations helped build the school directly across from his statue.

After a well earned siesta, we were back out in the evening for a tango performance. We arrived early and strolled around a bit

before heading in to our venue for the performance.

Dinner was included as well as a performance of tango by single couples

as well as multiple couples.

A singer performed Andrew Lloyd Webber’s “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina” in Spanish, which brought tears to many in the audience.

We were also regaled with folk music from the northwestern provinces while images of that region passed on the screen behind the performers.

Also from the folk tradition was a performance by a drummer

who also performed Malambo, a folk dance associated with the gauchos that features energetic stomping and complicated legwork, incorporating the use of boleadoras, weighted balls on cords. We were so happy to have visited the areas from which the folk music and dance had originated.

On our own in the morning we headed straight to the El Ateneo Grand Splendid bookstore. Built in 1919 as the Teatro Gran Splendid, it was converted into a bookstore in 2000, retaining its magnificent architecture. The world-renowned bookstore was once home to tango performances and early talkies.

Visitors can explore the theatre’s original architectural features, including frescoed ceilings, ornate balconies, and theatre boxes,

while browsing a vast collection of books. We were particularly amused by their choices of English-language books on display.

There was a full collection of Harry Potter

as well as numerous books about Taylor Swift found in the children’s’ section.

In addition to books we found numerous vinyl records for sale in the lower level.

The former stage now serves as a café, offering a unique spot to enjoy a coffee.

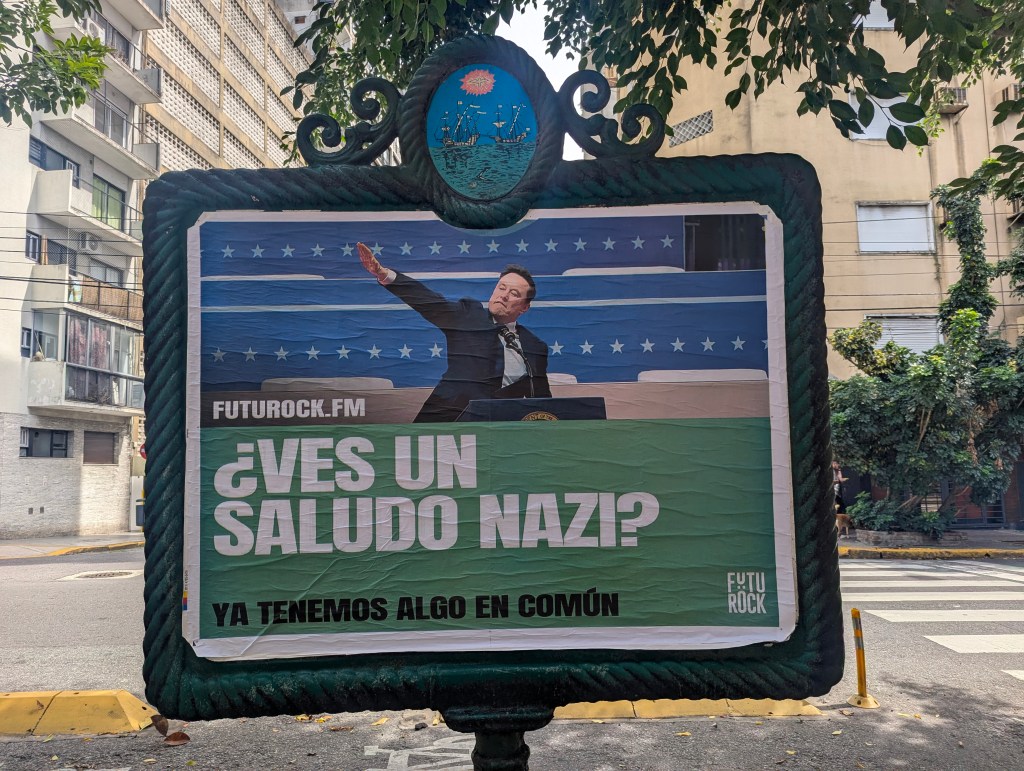

We continued wandering about the city. We were surprised by this advert for a streaming service; remember it was March, 2025 and our new administration back home was making a lot of headlines.

We walked past the Facultad de Derecho (Law Faculty) founded in 1821.

We also saw the Floralis Genérica (Generic Flora) a sculpture made of steel and aluminum located in Plaza de las Naciones Unidas (Plaza of the United Nations). It was created in 2002 and designed with a hydraulic mechanism which allows the petals to close at night and open in the morning symbolizing hope reborn every day at its opening. In 2023 two of the petals were knocked off during a storm and have not been replaced.

In the park we spied a monk parakeet.

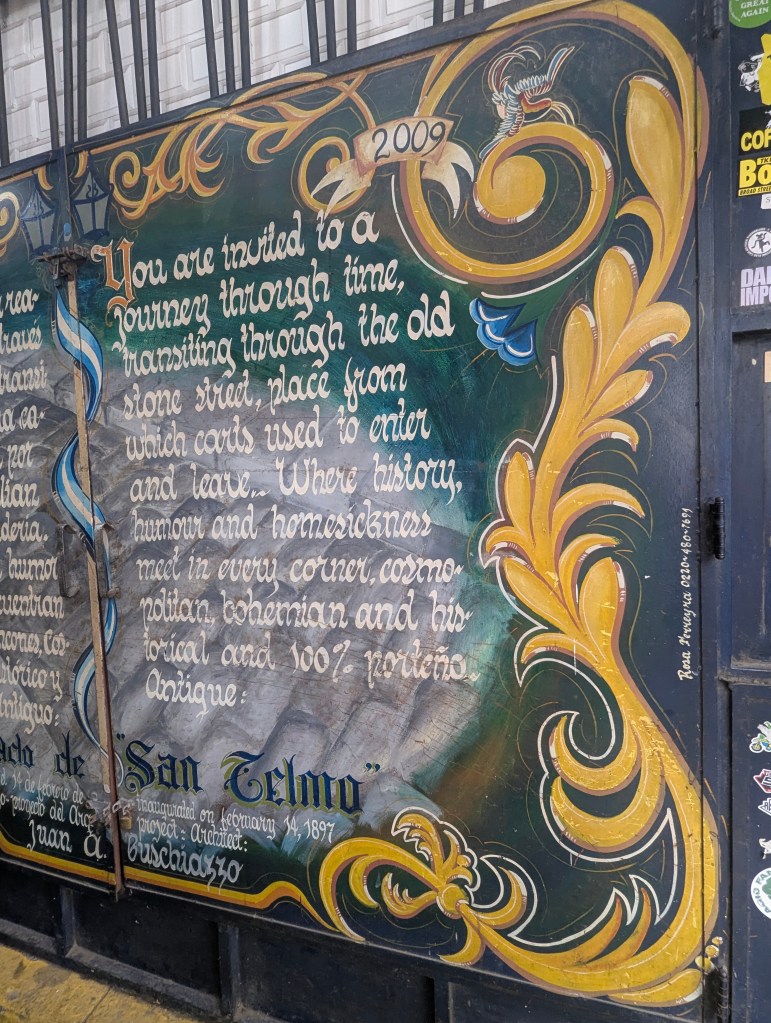

We ventured next to the Mercado de San Telmo (San Telmo Market).

Operating since 1897, the indoor section features original architectural elements like columns and beams.

San Telmo houses a variety of permanent stalls, including food vendors, antique dealers, and shops selling records and crafts.

We stopped for a quick bite to eat.

As we made our way back uptown, we began seeing some of the crowds of parades and protests to which Laura had alluded the day prior. To understand the events of the day, we needed a little more background history of Argentina. Juan Perón (1895-1974) was president of Argentina twice: as the 29th president 1946-1955, when his government was overthrown and he fled the country; again as the 40th president 1973-1974, when he died in office and was succeeded by his third wife. Perón’s ideas, policies and movement are known as Peronism, which continues to be one of the major forces in Argentine politics; his followers are Perónists.

In his youth Perón had traveled extensively throughout Europe which is where he picked up his socialistic ideology. Perón participated in the 1943 revolution and later held several government positions, including Minister of Labor, Minister of War and Vice President. It was then that he became known for adopting labor rights reforms. Political disputes forced him to resign in early October 1945 and he was later arrested. On October 17, workers and union members gathered in the Plaza de Mayo to demand his release. Perón’s surge in popularity helped him win the presidential election in 1946. Perón’s third wife, Isabel Perón, was elected as vice president on his ticket and succeeded him as president upon his death in 1974. Political violence only intensified and she was ousted by a military coup on March 25, 1976, initiating a period of military rule and state terrorism, the “Dirty War,” that lasted until 1983. Plaza de Mayo is now every March 25th on the site of the Argentine government’s commemoration of the Day of Remembrance for Truth and Justice. Participants carry signs that say “Nunca Mas,” (Never Again).

The signage was a mixture of a protest or indictment of the government.

and a memorial for those lost during the Dirty War.

Note the sign below has a pictue of Eva Perón. Evita came to Buenos Aires at the age of 15 to become an actress. She had come from a poor family. She met Juan Perón while he was in the military and subsequently Vice President. She helped form his socialistic platform. Together they helped develop the middle class as well as secure the vote for women.

The Edificio del Ministerio de Obras Públicas (Building of the Ministry of Public Works), built in the 1930s, features two giant 31-meter by 24-meter Corten steel murals of Eva Perón. First displayed in 2011 they show Evita both smiling on one side

and combative as she mobilizes the crowds on the other side of the building. She often gave speeches from the balconies of Casa Rosada.

She remains popular.

The crowds were impressivley large and non-violent.

Even the side streets were full.

Crowds even surrounded the Obelisco de Buenos Aires (Obelisk of Buenos Aires), a national historic monument and icon of the city. Located in the Plaza de la República on the intersection of avenues Corrientes, which leads to the Plaza de Mayo, and 9 de Julio, the Obelisk was erected in 1936 to commemorate 400 years since the founding of the city in 1536 by the arrival of Pedro de Mendoza (1487-1537).

For dinner we chose Estilo Campo in the Puerto Madero section, more on that later, for an Argentinean steak.

In the morning we had tickets to to the opera house which was very near to where we had seen the marchers the previous day. We walked by the obelisk; what a difference a day makes.

Teatro Colón (Columbus Theater) is famous for its magnificent building and, particularly, its near-perfect acoustics. The present Colón replaced an original theatre which opened in 1857 and was in Plaza de Mayo, where is now the National Bank, and was closed in 1888. The present theatre opened on 25 May 1908 after a 20 year construction process during which the first two architects, both from Italy, died. The first died at age 44, the second was murdered upon being discovered in bed with another man’s wife. The third and final architect was from Belgium.

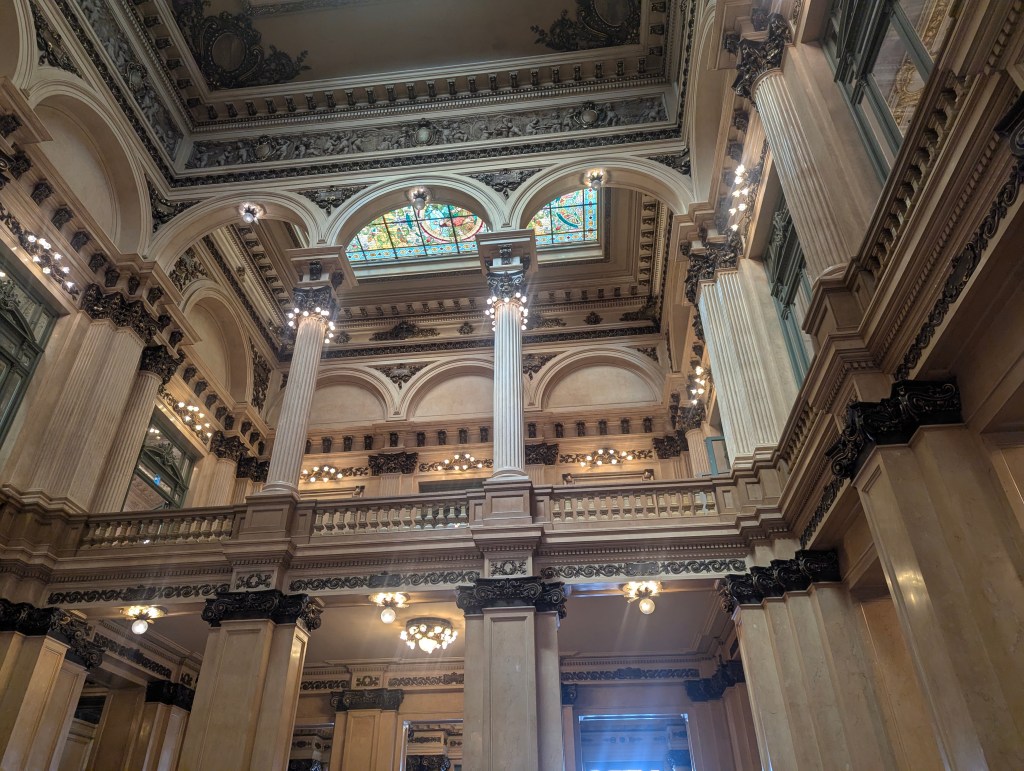

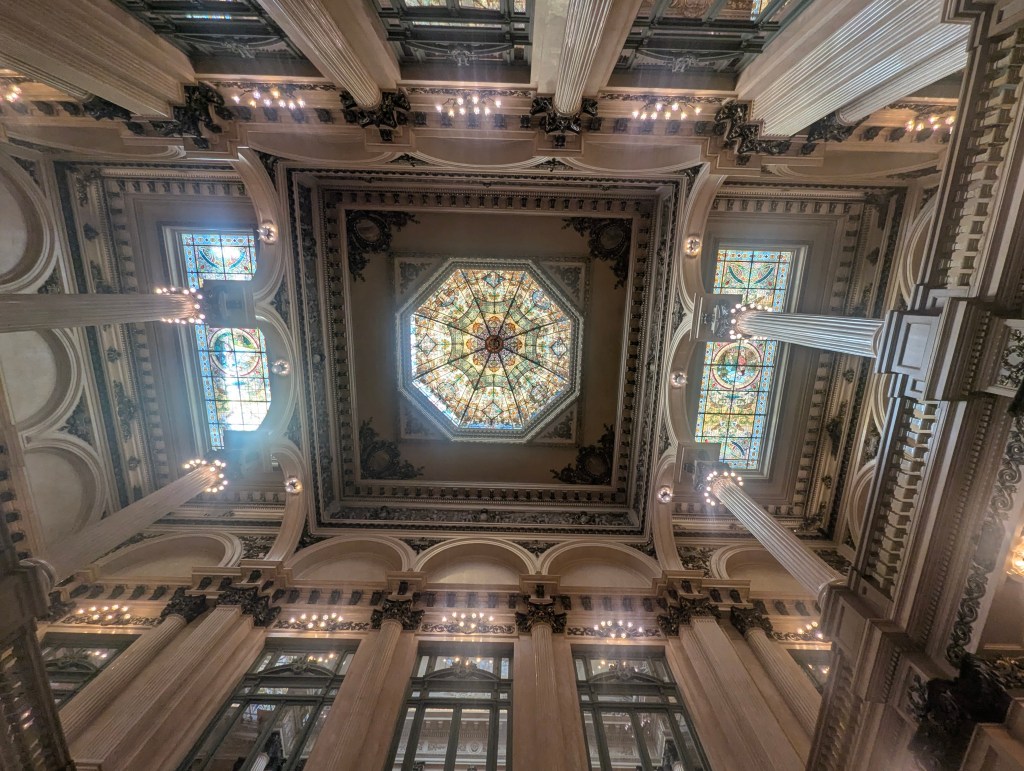

We took a guided tour with Lucia which began in the Main Foyer.

The floors are made of mosaic tiles from Italy.

The stairs are marble from Italy.

The red marble is from Spain, the green from Belgium, and the pink marble is from Portugal.

The stained glass originated in Paris.

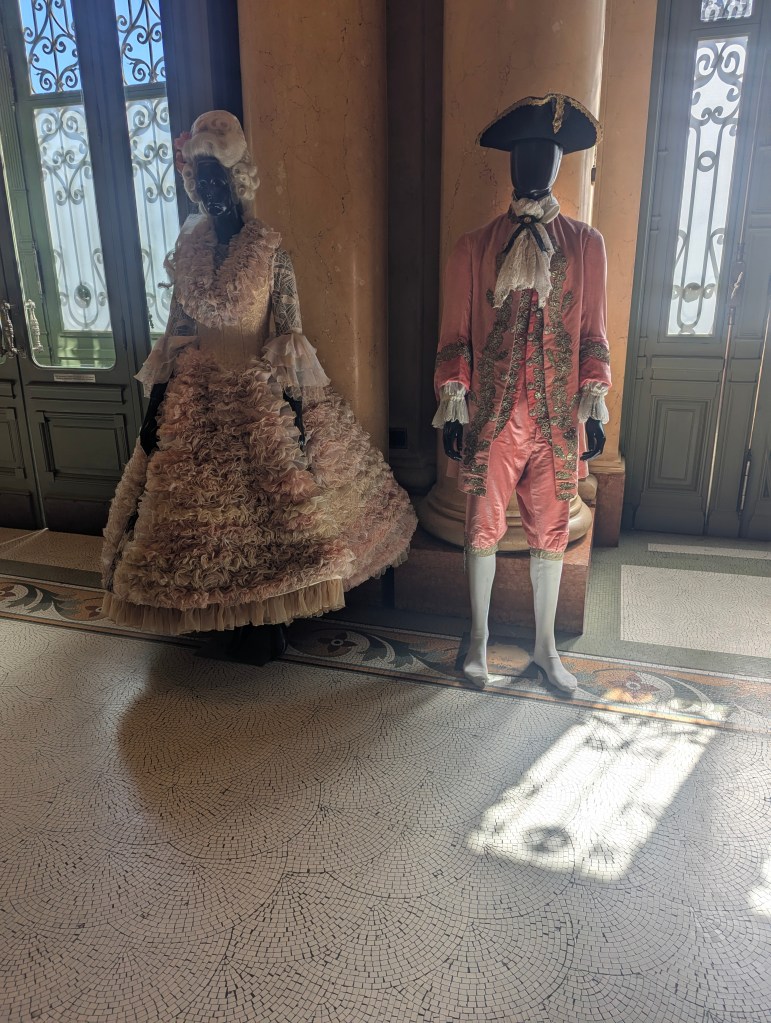

Most of the costumes and sets are made and stored in the basement factory, but a few were on display here.

On the way up the grand staircase our guide pointed out fossils in the marble.

On the upper landing we entered the Gallery of Busts which contains busts of many famous composers including Bellini

and Mozart.

Also in the Gallery of Busts is a statue by a German artist. It is made from a single block of marble and is titled “The Secret” depicting Cupid whispering into his mother Venus’s ear. Overall, the statue serves as an allegorical centerpiece. Amid the historical, commemorative portraits of composers, the mythological sculpture reminds viewers of love’s unpredictable, powerful, and mysterious influence, a fitting subject for an opera house where passion and drama unfold on stage.

There are more statues of cupids on the crown moldings; muses for the music.

The detail work in the crown molding is truly impressive.

From the Gallery of Busts is a view of the Main Foyer below.

On this level the Parisian stained glass can be appreciated from a closer vantage.

Next we entered the Golden Hall. The chandeliers are from Argentina, made of bronze, and have 222 light bulbs each.

Lucia pointed out that the lower half of the columns are painted gold

whereas the upper half are actually 24c gold leaf.

The sofas are 200 years old.

All of the furniture are museum pieces.

Finally we entered a typical 6 seat box

to the auditorium. The main hall can seat approximately 2,500 spectators, with additional standing room for about 500 more.

The boxes up front are usually reserved for officials and VIPs who want to be seen. There are black windows that can be placed in front for those who do not wish to be seen, eg widows in mourning.

This horseshoe-shaped hall is the heart of the theater, featuring stunning allegorical ceiling frescoes and an impressive, 2,866 lb chandelier, which can be lowered to change the 722 bulbs. (Actually, Lucia told us, they are not real frescoes but faux fresque, a technique that involves applying a painting onto a canvas and then transferring it to a wall or ceiling to achieve the appearance of a traditional, hand-painted mural or scene, such as a fresco.)

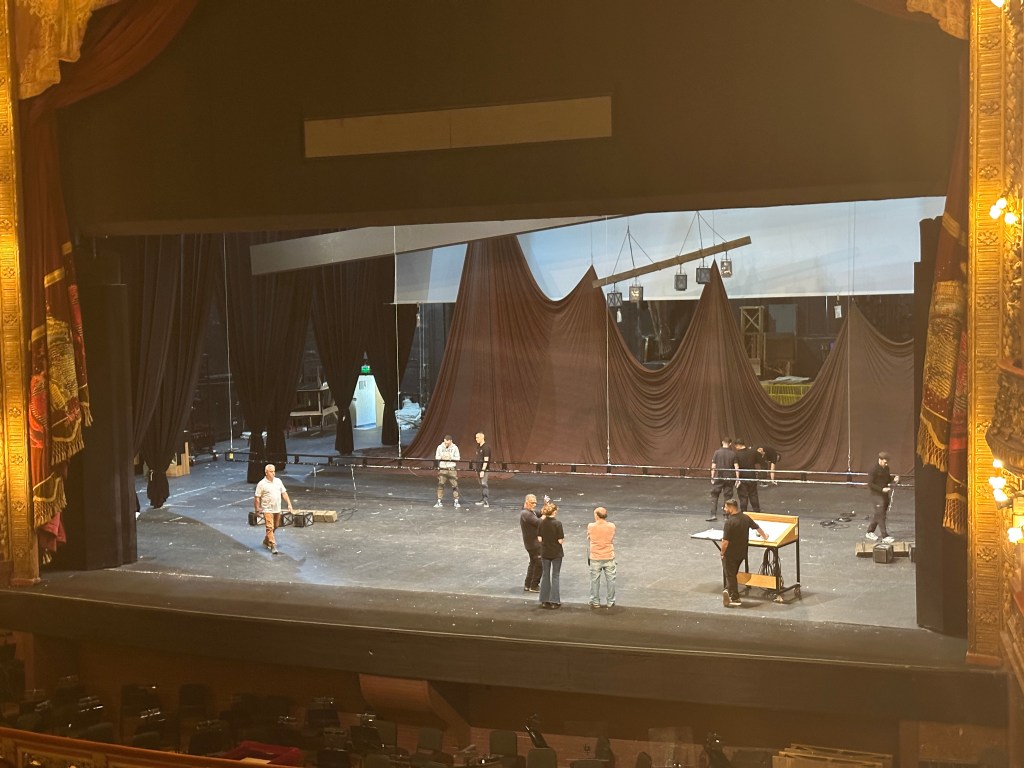

The orchestra pit holds 80 musicians and can be elevated to the same level as the stage. There is room for up to 18 more musicians under the balcony for special effects.

The Teatro Colón’s design, with its dome and horseshoe-shaped hall, contribute to its reputation as one of the best concert and opera venues in the world, especially with regards its acoustics. There are resonance chambers, hollow sound boxes, beneath every soft seat.

A closer look reveals a hollow box beneath an opening, similar to a guitar, for example.

The Teatro Colón is between the wide 9 de Julio Avenue, from which we arrived, and Libertad Street on which is the main entrance, though which we departed. We found ourselves on Plaza Lavalle. In 1856, the Parque Station was installed here, the head of the first railway line in Argentina, on the site where the Teatro Colón was later built. Looking around us we saw Mirador Massué, an old obeservation deck built as part of a 1909 construction designed by the architect Alfred Massué. Art nouveau influences can be seen in the curving facade and the use of iron and floral designs.

Right next to the theater is an impressive looking primary school built in 1903.

In the center of the park is a statue of Juan Lavalle (1797-1841) who was an Argentine military and political figure and former governor of Mendoza Province.

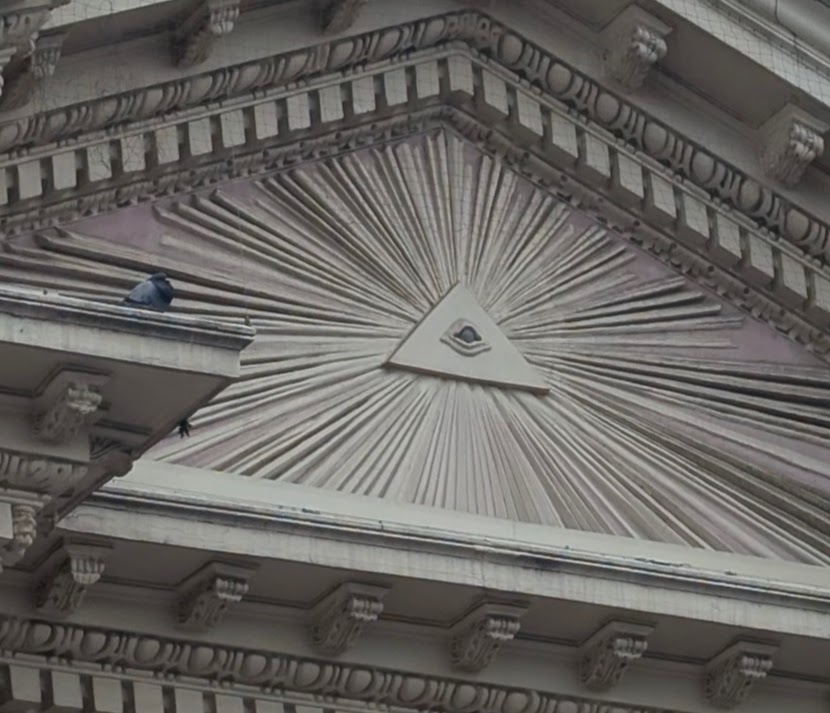

Behind the statue stands the Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación ( Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation).

We decided to head toward the capital building. Along the way we passed Palacio Borolo (The

Barolo Palace), an office building that opened in 1923 and, at the time, was the tallest in the city.

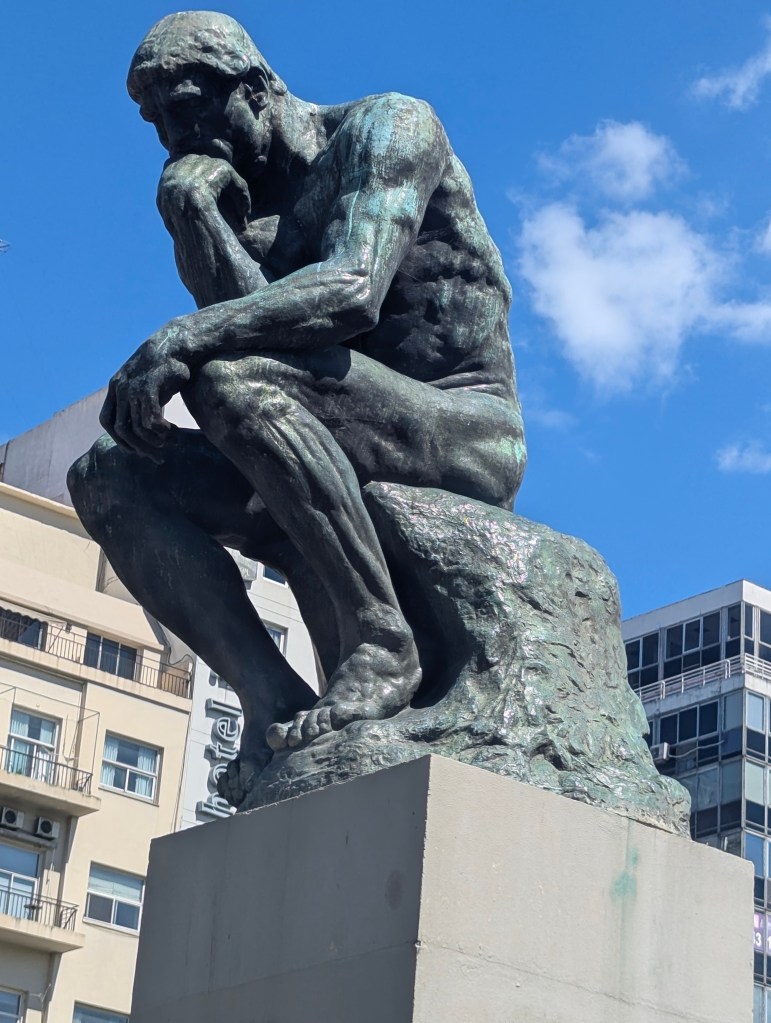

As we approached the capital we saw one of many official authorized casts of “The Thinker” by Auguste Rodin in the Plaza del Congreso (Congressional Plaza), a central public space in the Montserrat neighborhood of Buenos Aires.

Situated at the western end of Avenida de Mayo and located in the Montserrat neighborhood, Plaza del Congresso (Congress Square) is part of a group of three plazas located in the same area, next to Plaza Lorea and Plaza Mariano Moreno. The construction of these plazas was an urban development designed to coincide with the celebrations of the centennial of the May Revolution and responded to the hygienic thinking of the late 19th century , which rightly sought ventilated and sunny spaces in large cities.

Monumento a los Dos Congresos (Monument of the Two Congresses), inaugurated on July 9, 1914, is surrounded by a staircase that gives access to the platform, on which stands the monument crowned by a statue representing the Republic with a laurel branch in one hand and the other resting on the guide of a plow; at its feet are the serpents of evils and another figure representing Labor. The eastern platform is surrounded by a fountain with large jets, between which appear sculptures of horses surrounded by bronze condors and children representing Peace. The fountain extends to the east, and represents the Rio de la Plata and its tributaries. The pool is surrounded by sculptures of animals from the national fauna and in its center arises a sculptural group built in bronze.

The Palacio del Congreso de la Nación Argentina (Palace of the Argentine National Congress), constructed between 1898 and 1906, is a national historic landmark. The palace is in Neoclassical style, largely made of white marble with elaborately furnished interiors.

On the plaza is also the senate building: Senado de la Nacion (Senate of the Nation). The Senate has 72 members, with three elected from each of Argentina’s 23 provinces and three from the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires.

There we also found a building which houses the Centro de la Memoria, el Amor y la Resitencia (Center of Memory, Love and Resistance) with a picture of the white scarf worn by “Las Madres” (The mothers of the Dirty War).

In neighboring Plaza Moreno is a statue of Mariano Moreno (1778-1811) inaugurated on October 1, 1910. Moreno was an Argentine lawyer, journalist, and politician. He played a significant role in the movement for Argentina’s independence from Spain and a decisive role in the Primera Junta, the first national government of Argentina, created after the May Revolution.

We then headed back to Plaza de Mayo to get a glimpse of Casa Rosada without all the fencing surrounding it.

We walked around to the back of Casa Rosada and crossed the street to the Liberator Building, home to the Ministerio de Defensa (Ministry of Defense), one of the oldest ministries in the Argentine government, having existed continuously since the formation of the first Argentine executive in 1854.

In the plaza in front of the building is a statue of a soldier: a memorial to those who died in the Faukland War.

In January 2023, a commemoration plaque was placed to mark the 40th anniversary of the 1982 Falklands War, paying tribute to the veterans and fallen soldiers. Argentina claims the islands, which it calls Islas Malvinas (“Malvinas” is the Spanish name for the Falkland Islands), and disputes the UK’s sovereignty. The dispute escalated in 1982 when Argentina invaded the islands, resulting in the Falklands War. Having not participated directly in either world war, the Falkland War accounts for the largest loss of soldiers’ lives in Argentina since the revolution. The Malvinas (Falklands) War directly accelerated the collapse of Argentina’s military dictatorship, which was already facing economic decline and public opposition. The disastrous and humiliating loss of the 74-day conflict in 1982 eroded the junta’s credibility, leading to mass protests at home and international condemnation. This ultimately forced the military leadership to cede power and announce a transition to democratic elections, which occurred in 1983.

From across the street we had a good view of the back of Casa Rosada.

We crossed to Puerto Madero. Laura had told us that the area was once Buenos Aires’ second port (after La Boca), built in the late 19th century. However, the port was too shallow and small for modern boats and became obsolete after only 25 years, leading to the area being an urban wasteland, and the port was moved to its third and current location. The Puerto Madero land, which is all reclaimed land, is now the most exclusive and expensive in Buenos Aires.

Along the river are museums

and The Puente de la Mujer (Women’s Bridge), inaugurated in December, 2001. The design is a synthesis of the image of a couple dancing tango. It is a 170 m long and 6.2 m wide pedestrian bridge divided into three sections: two fixed sections on either side of the dike and a mobile section that rotates on a white concrete conical pylon, allowing the passage of boats in less than two minutes.

Also along the way are locks, which have come, throughout the world, to symbolize the everlasting love of the couple who places it.

The prior warehouses have all been converted into boutique shops and restaurants. We lazed away the rest of our last afternoon in one of them sipping beer and reminiscing about how much we have loved our visit to Argentina. We topped it off with a last gelato in the famous Luccianos’ right by our hotel.