Next we flew to Salta, which is the name of both the capital city as well as the province. With a population of about a half million, the city serves as the cultural and economic center of the Valle de Lerma Metropolitan Area. We arrived in the late afternoon and were told to be up and ready for a very long drive early the next morning. We ventured out into our local neighborhood to discover the peñas, places where Salteños sit and listen to their local folklore idols.

We lucked into a fantastic dinner .

with fun entertainment of local folk dancers and the soft instrumentals of the Musica de los Andes.

As promised, we were up and out very early to meet Gerardo, who was to be both our driver and guide for the next several days. Gerardo started with background history; Hernando de Lerma founded San Felipe de Lerma in 1582, following orders of the viceroy Francisco de Toledo; the name of the city was soon changed to “San Felipe de Salta”. There are several theories as to where the name Salta originated, but one of the most popular is the proposal that it is of Quechua origin, with “salta” possibly meaning “a pleasant place to settle down”.

Salteños like to brag that Salta is where Argentina’s independence from Spain was advanced. Gauchos were able to hide from the Spaniards in the mountains, traveling by mule. They were led by Martín Miguel de Güemes (1785-1821). Güemes, whose father was an accountant to the king, had been born in Salta, trained in the military in Buenos Aires, and returned to Salta in 1815 to lead the guerrillas against the Spaniards. He was subsequently appointed governor of the Salta Province.

As we drove through the Lerma Valley Gerardo pointed out the numerous tobacco farms and explained how the crops had to be genetically altered to tolerate the high elevations. Most of the tobacco from the region is exported to China. Most of the land has been owned by the Saravira family for over 300 years. The land is also rich with copper, silver, and lithium. We passed through El Carril, which means junction. It is famous for gauchos, empanadas, and tobacco production. Historically horses have been bred here. They are currently bred only for export to England and Dubai for polo.

As we drove along the Rio Rosario, Gerardo explained that the roads are often impassable due to flooding and rock and mud slides from the soft surrounding mountains. We crossed over a bridge, which gave us an opportunity to stop and take some pics.

We passed a red shrine and asked Gerardo about it as we had seen several on the road between El Calafate and El Chaltan. Gerardo explained that they are called Gauchito shrines in honor of Gauchito Gil, who is a folk hero in Argentina. Antonio Gil was supposedly born in the 1840s near what is now the city of Mercedes. He grew up to become a gaucho and for reasons unknown fled the army and went on to become a thief, perhaps a cattle rustler, who stole from the rich and helped the poor, a Robin Hood of sorts. He was eventually caught on January 8, 1878, and sentenced to hang. Before dying, he told the executioner that upon arriving home he would find his son very ill, but that he could be saved from death if the executioner prayed for Gil’s intercession. The man did as the Gauchito had told him and the son was miraculously saved. In gratitude, he returned to the spot where Gil had been executed, buried him, and erected a cross, thus giving birth to the cult.

Gerardo also pointed out regular shrines along the way, typical of the area.

The third type of shrines common on the roadside in Salta Province are apachetas, which are not just piles of stones; they are sacred spaces where travelers, initially Incas, leave small offerings, such as coca leaves, food, or small personal items, as a way to thank Pachamama (Mother Earth) for safe passage or to ask for blessings for their journey. They are often found in high-altitude areas like mountain passes, where the landscape is considered powerful and where travelers may feel closer to the divine. The placement of apachetas also serves as a guide, marking safe routes and indicating places of significance. To the unknowing tourist, it could look like a pile of rocks and trash.

As we drove out of the fertile valley and up into the mountains, Gerardo pointed out the cacti. There are two main types of cacti that grow in this region. The faster growing ones, depicted below, are the candelabra cacti, which can grow as much as 2 inches a year.

We stopped at the Mirador de la Cuesta del Obispo with a view of the Lerma Valley. Unfortunately, the day was a bit overcast making the panoramic views not quite so magnificent.

But what we lacked in drama was made up for by all the fauna we saw along the way. This fox greeted us at an overlook.

and was interested in us

until he found his friend.

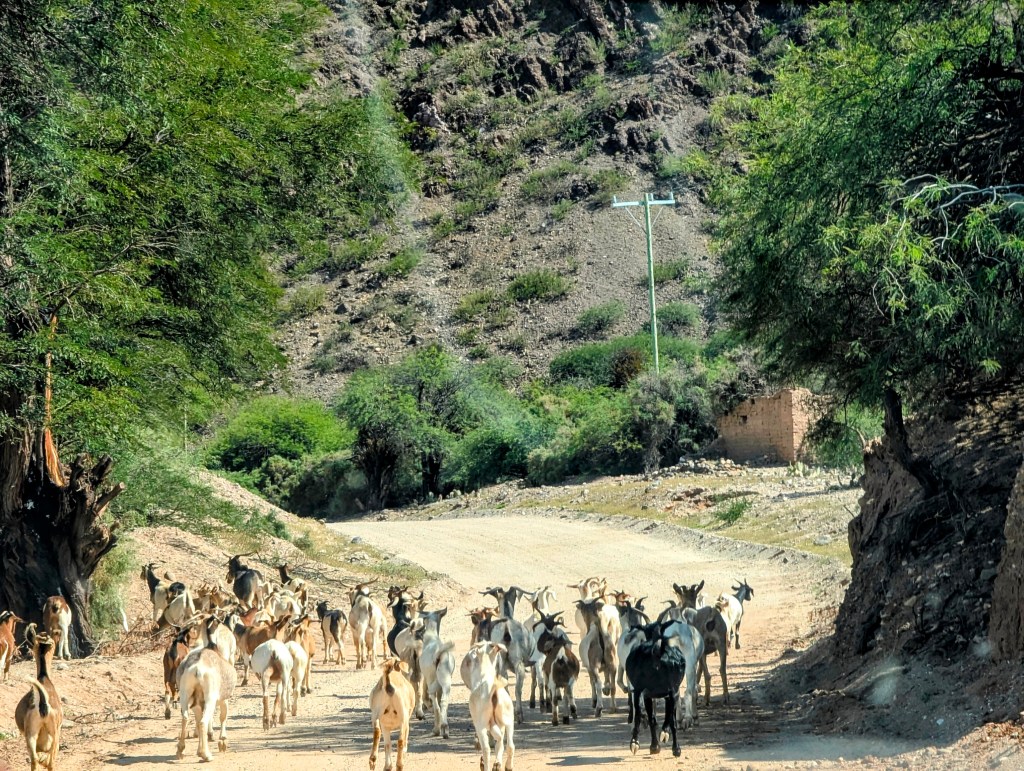

We saw tons of sheep and goats up on the mountain ridges.

as well as cattle grazing right along the side of the road.

We passed very few houses along the way. The few we did see were powered by solar power. We made a bathroom stop at Pie de la Cuesta.

There we met a van full of American bird watchers. They were looking for toucans but found for us a great kiskadee, known for its distinct vocals.

From here we were at an altitude of over 200 m (6500 feet) and climbing. We learned that llamas can only live at these high altitudes. We reached our peak for the day at:

Next we entered the Parque de los Carbones, the park featuring the second type of cactus found here: the slow growing carbones at less than a half an inch a year. We stopped at the Piedra de Molina (Millstone).

and visited the Capilla de San Raphael (Church of Saint Raphael).

Eric bought llama sausage from a local.

Hunting is prohibited in the park, so the wildlife is abundant. We saw lots of guanacos.

We pulled over and hiked up to the Mirador Ojo del Condor (Lookout of the eyes of a Condor) for a view of the cacti-filled valley below.

Once down in the valley, we hiked amongst the cacti. Growing at only a half inch a year, the oldest are close to a thousand years old!

The fruit of the cardone tastes a bit like kiwi. Each fruit has many seeds, but only one will grow into a cactus.

Once it falls to the ground and germinates, the developing cactus is protected from the harsh sun by the jarilla bush.

We passed along the almost 11 miles of Tin-Tin Straight (Recta de Tin-Tin) notable as a remnant of the Inca road system, built over 500 years ago when the Incas arrived from Peru in about 1430, about 100 years before the Spaniards arrived and conquered the natives. Now the road is a high altitude winery route.

We travelled through the Calchaquí Valley, which means “moon farmers” because the farming here follows the cycles of the moon especially for farming paprika. We stopped for lunch in Cachi which has a population of about 7,000. It is known for its colonial architecture, particularly its white adobe buildings. The church has 3 bells, unusually all on the same stick.

We found a local restaurant and tried all the local favorites: locro, a squash stew.

stewed goat

and tamales.

After filling our bellies, we wandered around town a bit. Cachi is the paprika capital of Argentina.

Paprika production basically involves drying the peppers in the sun.

They also make and sell alfajores here, a favorite sandwich cookie of Argentina.

We noted the “welcome condor”

and strolled through the artisan market.

After lunch we were back on the road. We made a bathroom stop in Molinos with its Pueblo Church

beautiful hotel: Haciednda de Molinos. The hacienda is a refurbished 18th-century building, once the home of the last royal governor of Salta, preserving its original colonial charm with features like adobe walls and carob tree ceilings.

The enchanting courtyard exhibits one of these ancient carob trees.

Across the road is a nature preserve.

Then again we were back on the road. We passed adobe houses abandoned over 200 years ago. I cannot stress enough how rough the drive was for Gerardo who navigated many areas of washed out or flooded dirt roads not to mention maneuvering around the herds of animals. And we were over 11 hours on the road in just the first day.

But the scenery was stunning, making the long hours worthwhile.

Our post lunch drive passed 15 million year-old mountains.

and natural monuments.

Pictures barely capture the beauty of the landscape.

Choosing which pictures to include was not an easy task.

We stretched our legs on a mini hike up to a mirador.

It was early evening when we reached Cafayate and checked into Hotel Comfort.

Cafayate is a cute town with a population of 15,000 and sits at an altitude of 5,600 feet. Cafayate is one of the highest regions in the world that is suitable for viticulture. After settling in we went to the town square and had dinner in a cute outdoor cafe with live music.

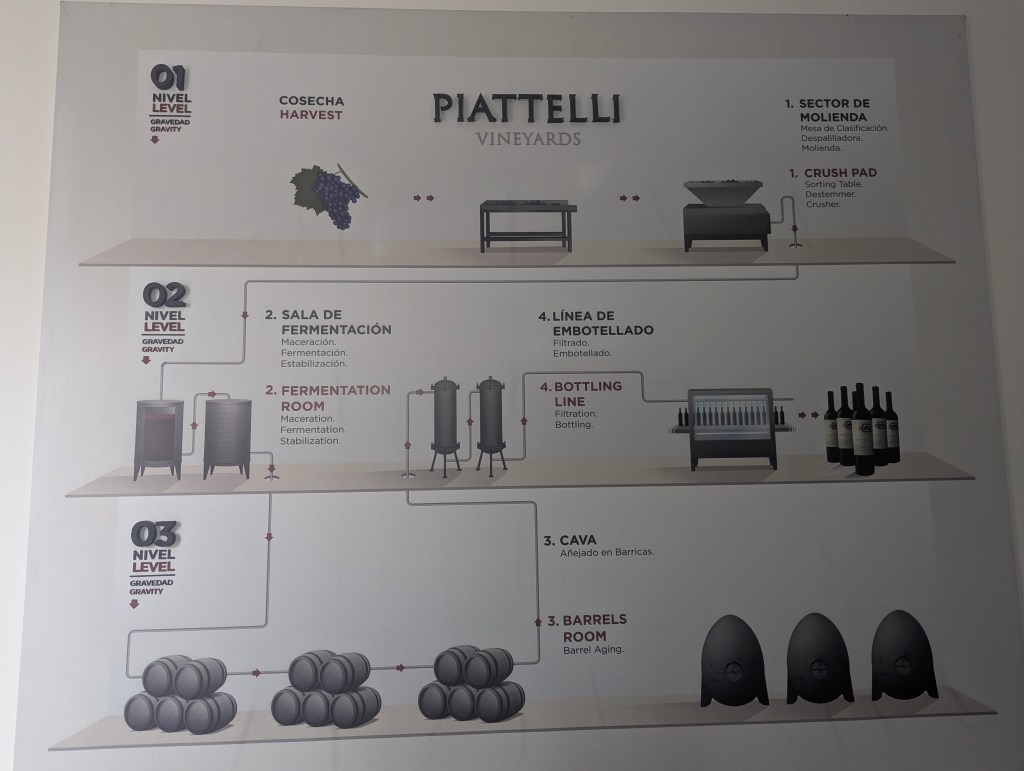

In the morning we started our “high altitude wine” tour. First stop was Piattelli.

This high altitude is what defines the region and makes it suitable for growing grapes despite its close proximity to the equator. Due to the high altitude, Cafayate receives intense sunlight which causes the skins of the grapes to thicken significantly as a protection against the sun. Though the days are bright and warm, true to a desert climate, the nights can be very cold which causes the growing season to be extended and ultimately leads to a balanced structure in the end.

The soils in Cafayate consist mostly of free-draining chalky loam and in some areas can be quite rocky. The dry soils cause stress in the vines which causes them to produce less vegetation and not as many grapes. One would think this is a bad thing, but in fact, it proves to be very good and that less, truly is more. As there are fewer grapes, all the work the vines do to get these few grapes the nutrients means the concentration of flavors within the grapes rises. As Cafayate is a desert-climate, and has very low rainfall and humidity, the vines rely on the meltwater from the Andes to keep hydrated during the particularly dry periods.

The original Piattelli Vineyard is in Mendoza, since 1940, which is where their Malbec grapes are grown. The current owner, from Minnesota, bought about 250 acres in Cafayate in 2007. Here they started producing wines in 2013. A majority of the grapes grown here are Torrontés, a white grape varietal. Due to the high altitude (anything above 5,900 feet is considered high altitude) the skin of the grape is much thicker. The water source is underground aquifers via pumps.

The Piattelli method of winemaking is a little different than what we had seen in Mendoza.

The Torrontés grapes are now considered to be native to Argentina. But local lore claims the grapes were originally brought to the area from Spain by Jesuits in 1879. But the Jesuits were killed by the king of Spain, and wine was then reintroduced to the area by French brothers.

Sorters with vibrators make hand sorting and cleaning easier.

The Torrontés grapes are first fermented at 46 degrees F to take away sediment then 57 degrees for sterilization and clarification. They are never in oak barrels nor do they age in bottles, only steel. Their red wines, however, do go into underground barrels of both French and American oak.

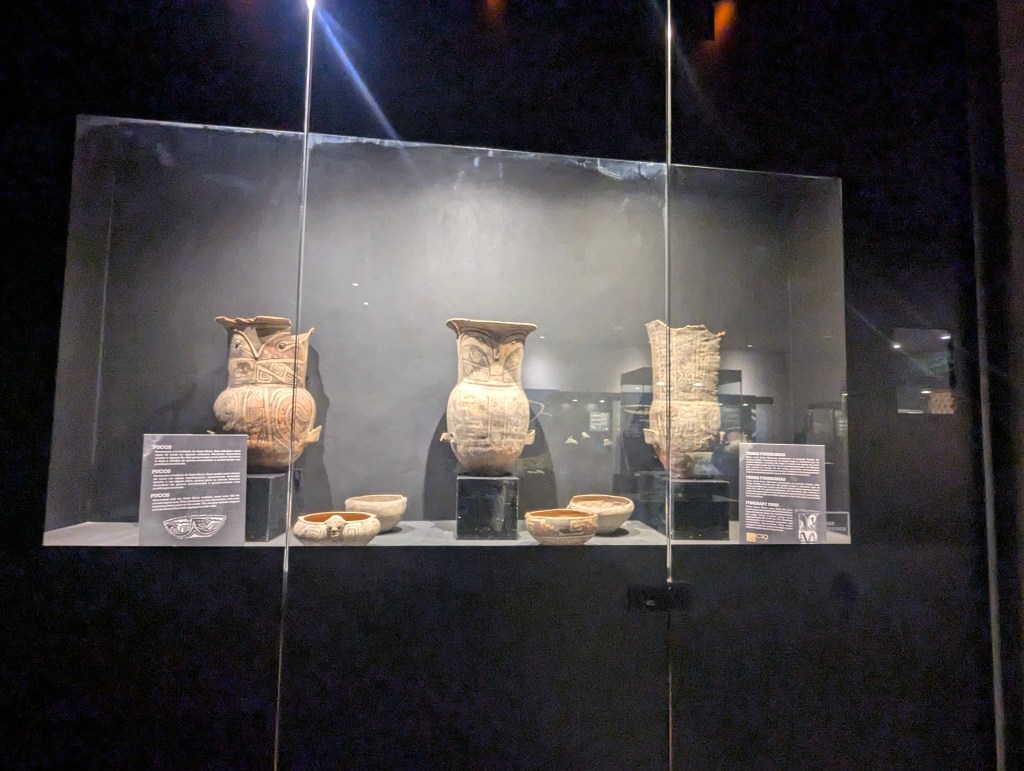

The wine cellar at Piattelli has a small exhibition of early Americans.

including samples of pottery

and art depicting early life here.

Then, of course, we had a tasting.

Our next stop was the family owned Viñas en Flor winery at an altitude of 5100 feet consisting of about 250 acres bought in 2004. The first wines were produced here in 2014.

Because of the time, we started with lunch, which was truly gourmet, before the tour.

The desert was one typical to the region: crepe with dulce de leche, which is a rich, sweet, and thick caramel-like sauce made by slowly cooking milk and sugar until they caramelize and thicken.

Of course we had wine with every coarse. We loved the artwork on the bottles.

We were so full we had no room for more tasting, but we were taken on a tour of the winery which includes a guesthouse as well as a restaurant. But construction for now has been halted, they claim due to limited funds due to decreased tourists due to policy changes of the new Miele government. What is particularly special about Viñas de Flores is they use trellises to protect the vines from the intense equatorial sun, although it was late in the season and not currently in use.

Next stop was Nanni Winery, a family-owned winery founded in 1897. In 1986 they received the organic certification, one of the few in the area. To be organic they need a 4.3 mile perimeter from vineyards using chemicals. One of the many insect deterrents is the use of white roses. Their 120 acres, relatively small, are at 5400 feet and contain only torrentés grapes. Due to the small production, they do not sell outside Argentina.

We did not love their wines, but we did enjoy some of their artwork

and the very old door.

Interestingly, they do not use cork in their bottles, instead it is the base of the sugar cane plants, which are abundant in the area on the sunny side of the mountain range.

Done with wine tasting for the day, we strolled around Cafayate, which is basically a square with a few side streets..

Prominent in the town square stands the 1885 Cathedral of Our Lady of the Rosary.

Eric sent up the drone for a birds’ eye view of Cafayate.

We turned in for the night.

In the morning we left Cafayate. We briefly left Salta Province and entered Tucuman Province, considered the nation’s birthplace. Its Casa Histórica de la Independencia museum in the capital city of San Miguel is the spot where independence from Spain was declared in 1816.

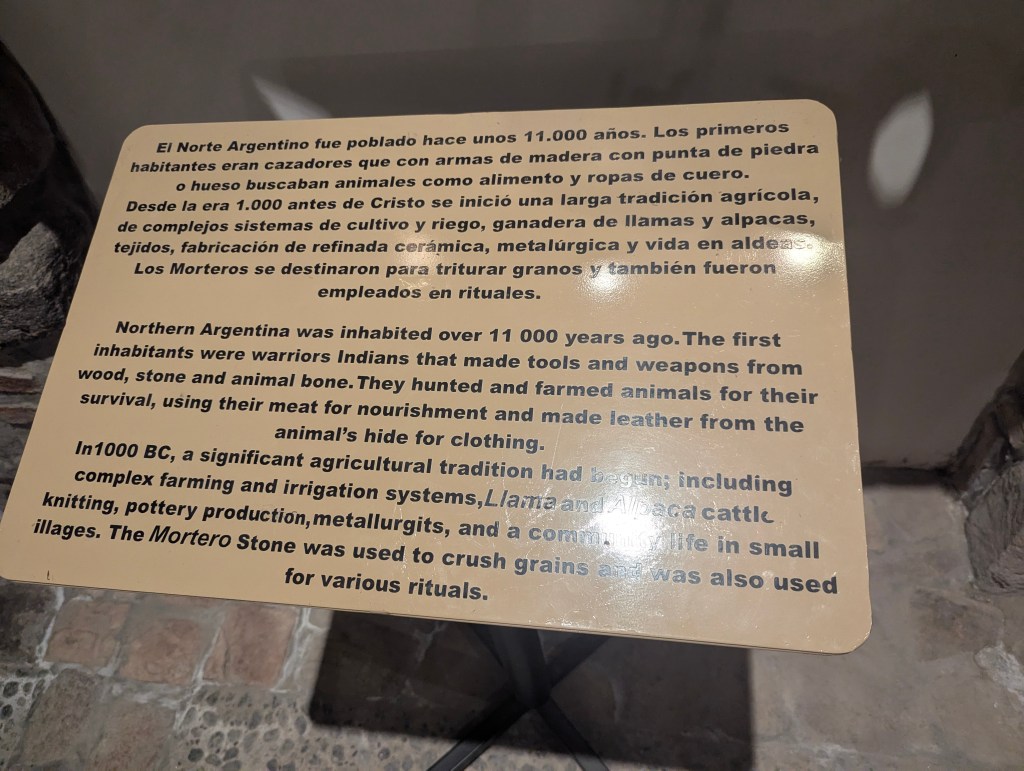

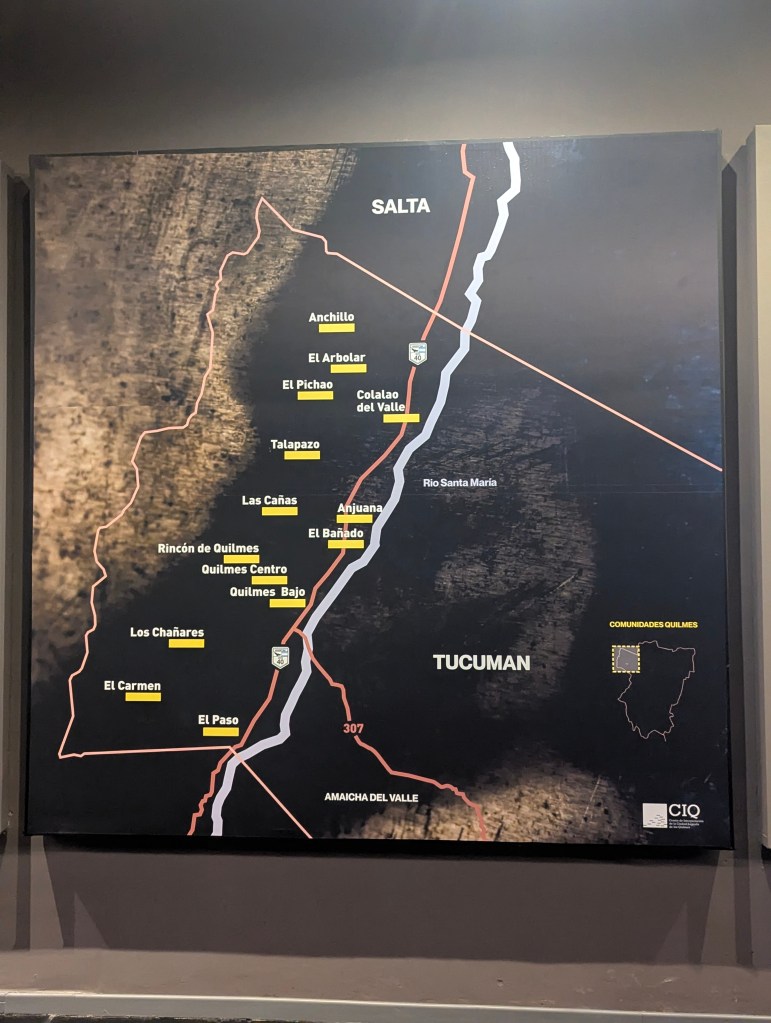

We drove through the Colalao Valley to the Quilmes Ruins, The site was the largest pre-Columbian settlement in the country, occupying about 75 acres The area dates back to c. 850 AD when the peregriños de sueno (pilgrims with a dream) arrived. It was inhabited by the Quilmes people, of which it is believed that about 5,000 lived here during its height. It should be noted here that the Quilmes are the only native peoples that have descendants living in Argentina today; the rest were killed or exported as slaves by the Spaniards. The Quilmes had survived the invasion of the Incas only to succumb to the Spaniards. In 1665 the Spaniards took the 2600 Quilmes who survived the battle and marched them to Buenos Aires; only 899 survived the journey.

First we visited the museum to learn about the Quilmes people, their communities, their crafts

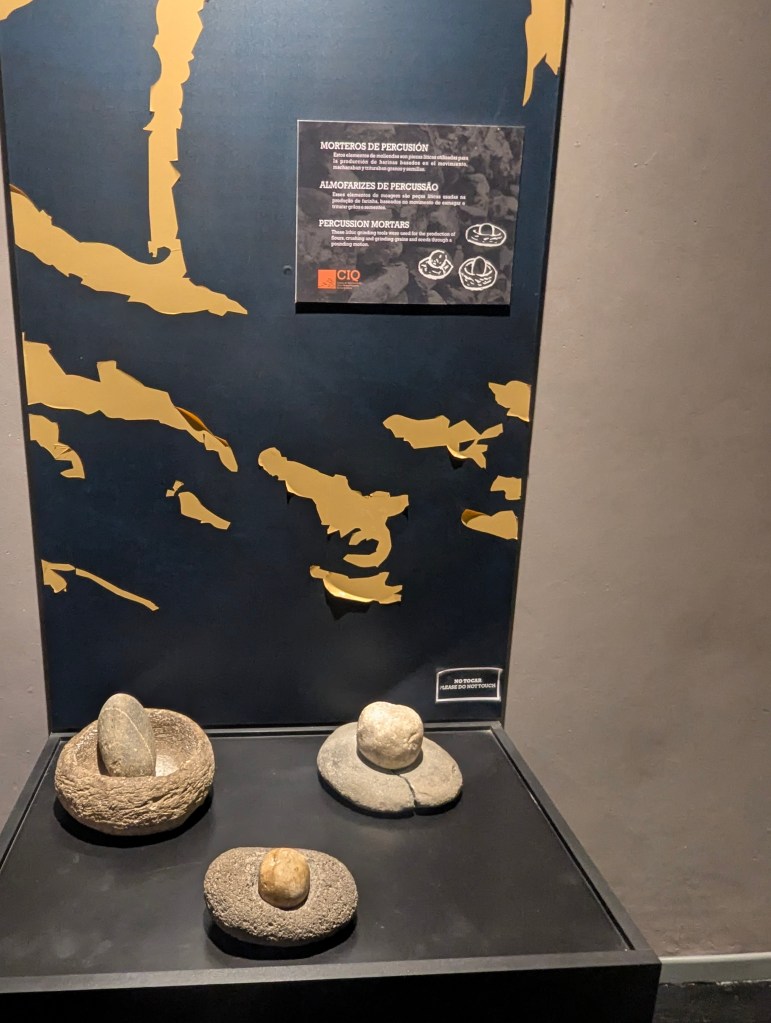

and their tools

They had planted crops and used channels from the river for irrigation systems. They were artisans, farmers, and shepherds. They had an organized social community based on families and a ruling chief: caciques.

Then we went outside to the ruins of the pucara (a prehispanic defensive hilltop site or fortification) first discovered and studied in the 1880s. (The view from above looking down is better.) This picture shows how the land envelopes the area and has peaks from which watch posts could be manned for protection of the community.

We noted the alter at the base of the ruins.

The work zone has a room for grinding corn and wheat.

And there are numerous homes.

As climbed up to one of the side forts, we noted the decorations included in the building process.

From the fort is a better view of the ruins.

The panoramic distorts it, but gives a feel of the enormity of the ruins.

Back in the truck we retraced our morning drive and made one last winery stop for lunch in Cafayate at El Povenir Winery.

El Povenir sits at over 4900 feet and its first vines were planted in 1945. They receive less than 10 inches of rain a year, true desert-like conditions, so irrigation is a must and uses gravity and streams from the mountains. They also use a pergola system to protect the vines from the harsh sun. The current owners are the fourth generation of the same family. A unique element of the vineyards here is that they grow red and white grapes intermingled.

Before lunch we had yet another wine tasting. A first for us here was a narango (orange) wine, which is produced from white wine grapes fermented with their skins for a short 45 day maceration, giving it an amber color and complex flavor profile. It is a winemaking technique with ancient roots but experimental for this winery. It is a bit more citric tasting, but the name is for the color. It is best served with spicy food.

We then enjoyed another gourmet meal with wine at every coarse (and we wonder why we are gaining weight). A highlight was the homemade ravioli. There were so many Italian immigrants to Argentina, pasta is included in almost every meal and certainly on every menu. There are no separate, distinct Italian restaurants in Argentina as we have them in the US; the food is integrated into the Argentinian cuisine.

As we enjoyed our meal we watched preparations for a wedding the following day. El Povenir includes a beautiful resort.

They have beautiful plants throughout, but we were particularly impressed with the cacti.

After lunch, we returned to the city of Salta, driving along the Quebrada de las Conchas that originated in the Tertiary Age, 70 million years ago and divides the Lerma Valley and the Calchaqui Valley. Along the Quebrada de las Conchas we were impressed with the many rock formations and their colors

and the Conchas River, which is the same as the Calchaqui River, but the name changes.

The area is a protected preserve but is not yet a protected national park. There is uranium, which makes the locals anxious about the future of this beautiful landscape. Wind erosion has formed a succession of capricious natural phenomena such as Los Castillos

El Obelisco (the Obelisk)

El Amphitheater (The Amphitheater) with excellent acoustics

inside The Amphitheater

and Garganta del Diablo (The Devil’s Throat), a deep and narrow canyon.

Once inside, there were some who climbed, but we were not that brave.

After three long days, back in Salta the next day, Gerardo rested while we took a walking tour of Salta with Veronica. She furthered our Salta history explaining that the city was founded in 1582 by the Spanish conquistador Hernando de Lerma, who arrived from the north when he found the valley by following an Inca trail. He intended the settlement to be an outpost between Lima, Peru and Buenos Aires.

The statue of Hernando is in Güemes Park named for Miguel de Güemes who, as mentioned above, as the local military leader under the command of General José de San Martín, defended the city and surrounding area from Spanish forces coming from further north between 1815-1821.

Across from Güemes Park is the Salta Province Parliament building.

Veronica pointed out that in addition to Spanish influence, particularly that of Andalusia, there is French influence in the architicture, as can be seen in the building below, originally a private home, now a hostel.

We approached the basilica from the back.

and found ourselves at the main square of Salta, the July 9th Plaza, Independence Day. It was on this day in 1816 that the Congress of Tucumán declared Argentina’s formal independence from Spain.

At the head of the square sits the Cathedral Basilica of Salta. In 1856, after an earthquake in 1844 had destroyed the original church on this site, plans and subsequent construction of the new basilica were begun; it was completed in 1882. The original simple church had been built in 1592 and had been expanded by 1000 Jesuit pilgrims sent from Peru in 1692. In the late 18th century, Franciscans replaced the Jesuits, who were thought to be too aggressive with killing the local indigenous people. When the church was destroyed in the earthquake, a statue of the Virgin survived, considered a miracle, and is now the “protector” of the basilica.

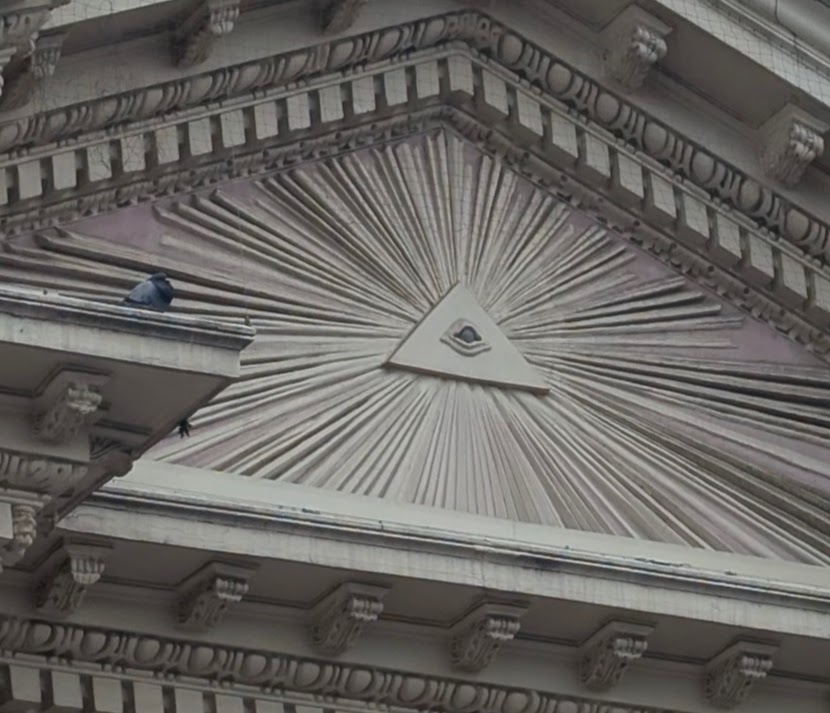

Unfortunately, every time we passed the basilica there was either a mass in progress or it was closed to the public, so we never managed to get inside. Veronica told us that instead of lighting candles, the devout bring carnations: red for the Lord, white for the Virgin. Veronica told us that the Franciscans introduced the violin, which quickly became adapted with the local music. They also introduced Baroque art; everything inside is adorned with gold leaf, as can be seen above the entrance.

Veronica pointed out the all seeing eye of the lord over the entrance to the basilica.

Pope John Paul II visited in 1986.

Veronica pointed out other buildings around the square including this mid-nineteenth century palace, with a neo-Gothic façade of Victorian imprint, which was a school for ladies studying to be teachers or nurses

and this prior boys’ school built in 1919 and now part of the Centro Cultural América.

The Museo de Arqueología de Alta Montaña (Museum of High Altitude Archaeology) was inaugurated in 2004 to preserve, research and exhibit a unique collection; more on that later.

The orange trees around the square provide shade. The oranges are too bitter to be eaten but instead are made into marmalade.

The Cabildo de Salta, the parliament building from 1626 until 1821, was originally built with adobe walls, mud-cake roofs and no tower. In 1789 masonry arcades, tile roofs, and the iron railings of the upper floor, as well as the balcony and carved figures of angels with indigenous faces were added replacing the earlier, more modest structure. The tower of the Cabildo was erected as an independent structure in 1797 with the purpose of locating in a visible place the public clock that had been removed from the then Church of the Company of Jesus. Ultimately the clock was moved to its current place on the Cathedral Basilica of Salta. The Cabildo is now a museum.

The weather vane’s figure looks like a leprechaun but is supposed to be a Saltanian.

The balconies seen are typical to Argentina and are similar to those used by Eva Peron to address the crowds.

In the center of the plaza de Julio 9 is a monument.

Inaugurated in 1919, the statue represents and pays homage to General Juan Antonio Álvarez de Arenales, an outstanding figure in the struggle for independence, declared on the 9th of July, 1816. Álvarez became governor of Salta in 1824. The 12 female figures around the base symbolize the 12 muses as well as the 12 original provinces (there are now 24 provinces in Argentina).

On the corner of the square sits a statue of Gustavo “Cuchi” Leguizamón (1917–2000), an Argentine poet, composer, and musician born in Salta. Cuchi brought a new harmonic freedom to Argentina’s traditional folk music, inspired by 20th-century composers.

Across the street from the square sits the pink Salta Hotel. Built in 1942 it was the city’s first hotel.

Down Caseros street is the San Francisco Church and Convent. The Franciscan order received the land for the complex shortly after Salta was founded in 1582. Construction on the current church was begun under the direction of Fray Vicente Muñoz, with the first stage of construction concluding around 1625. The church underwent significant reforms in the 1870s and was further embellished by Italian architect Luis Giorgi, who added Neoclassical and Baroque details. The current convent was originally a hospital.

The symbolism in the reliefs have somewhat typical catholic themes.

But Fray Muñoz also showed respect for indigenous people’s beliefs, and incorporated many of their symbols like condors, swallows, frogs (which represent fertility)and snakes into the art works.

The interior is typical Franciscan-style: simplicity of design, single nave, wood and local materials and an unadorned alter.

San Roque is the protector of dogs. The legend is that Roque was traveling, became injured and immobile on the road. A dog found him and brought him bread daily until his family found him. On August 16th, the annual feast day commemorating him, parishioners bring their dogs to church.

On September 15, Salta, celebrates the “Fiesta del Milagro,” a significant religious pilgrimage honoring the Lord and Virgin of the Miracle with a large procession through the city. The event commemorates the end of the earthquake in 1692 and involves hundreds of thousands of pilgrims traveling from across the province and country to renew their faith.

As we walked, we asked Veronica about the large crowds of people we see outside certain doors in the evenings. She explained that they are English language schools. She told us that the economy has gotten so poor for the average worker in Argentina, many must choose between education for their children or health insurance for themselves. The public schools have been so weakened in recent years by government cuts that children in public schools only go half day, either morning or afternoon. They are ill prepared for college. By learning English they are hoping for jobs in the growing tourism industry. But without health insurance, they are at risk. With recent cuts in the public health system many rural public hospitals and clinics have closed. The refrain we heard several times is “if you get sick, you die.” Veronica took a moment to point out shops along the way, including this one selling alpaca wool.

San Bernardo Convent is the oldest religious construction in Salta. A chapel dedicated to San Bernardo, second patron saint of the city, was erected in this place at the end of the 16th century. Destroyed by the earthquake of 1692, it was rebuilt in 1723. Today only 16 nuns live here.

From the architecture point of view, the most interesting feature is the entrance.

After our walking tour with Veronica, we went back to Museo de Arqueología de Alta Montaña (Museum of High Altitude Archaeology), aka MAAM. There we were not allowed to take photos, but were awed by what we saw. The collection includes the mummified bodies of two children and a young woman from the Inca period, offered to the gods in a Capacocha ceremony on the Llullaillaco (translated from Quechua to: lying water, ie glaciers) volcano (22,110 feet), at the border between Argentina and Chile, with over 100 burial objects. The bodies were found in 1999; the museum opened in 2004. For the Incas, nature was sacred and the higher the place, the closer to the sun, the more holy. They were fond of mountain shrines, huacas, with over 200 in the Andes, 50 of which are in the Salta province. Capacocha was an important sacrificial rite that involved the sacrifice of children. Children of both sexes were selected from across the Inca empire for sacrifice in capacocha ceremonies. The children of chiefs from different territories were first married to unite the kingdom, then given alcohol and coca leaves to make them sleep, then buried in the chupas while still alive to “meet their ancestors.” Only one of the three mummies is on display at any time to both protect them all and allow for further research. It was stunning how incredibly well preserved the bodies are today.

After the museum we headed for our big meal to celebrate my birthday! We ate in a local restaurant specializing in the all the regional specialties: tamales, locro, empanadas, and more. We tried them all.

In the morning we were back with Gerardo for another road trip. Our first stop was to see the Estación Campo Quijano (Quijano Train Staion), which was the home of the world’s highest steam engine train, reaching altitudes over 15,000 feet. It no longer operates because the abundance of landslides in the area made it more costly to maintain than the politicians were willing to support. It originally carried animals, tobacco, and other agricultural products; there are over 3000 varieties of potatoes grown regionally. But more recently it has been used by the lithium mines.

As we ascended through the Quebrada del Toro (Bull Gorge) we could see remnants of the now defunct railroad.

I have mentioned, both here and previously, the numerous landslides. Many times during our drive Gerardo has had to maneuver around and/or through massive amounts of mud and water on the road. We asked him to pull over at one such spot to record just how difficult road maintenance is in the region.

As we drove Gerardo pointed out ruins that he explained were “typically Incan” because of their square structures.

He also pointed out the roadside Difunti Correa, a small shrine. According to popular legend, the husband of Deolinda Correa was forcibly recruited around the year 1840, during the Argentine civil wars. When he became sick, he was abandoned by the Montoneras (partisans). In an attempt to reach her sick husband, Deolinda took her baby and followed the tracks of the Montoneras through the desert. When her supplies ran out, she died. Her body was found days later by gauchos who were driving cattle through San Juan Province. They were astonished when they saw the dead woman’s baby was still alive, feeding from her “miraculously” ever-full breast. Gauchos and truck drivers leave bottles of water on the shrine to “quench her eternal thirst”. The roads were historically trade routes passing through the desert, used for trading livestock to Chile in exchange for copper.

We passed through Alfacito, the only town in the area with a school. Children must get themselves to school from the mountains. We passed ruins of a 1200 year old animal corral and 600 year old Inca buildings. We stopped in Santa Rosa de Tasil (bell stone). When the stones are struck with metal they ring.

We toured the tiny museum

and visited the small chapel.

We then passed over Abra Blanca (high mountain overpass) at an altitude of over 14,000 feet. The views were stunning.

with, of course, a shrine.

Along the way we passed llamas and vicuñas. Both are only found above 6000 feet. Vicuñas are native to Argentina for over 5000 years; llamas were brought by the Incas. Both are in the camel family (as are guanacos) but are better for the environment because they only eat fresh leaves which does not kill the plant. We were told by Gerardo that this sighting of them together is rare. The vicuñas are the smaller light brown deer-like animals in the middle. Vicuñas are smaller, more delicate, and more skittish than guanacos; the latter live in lower altitude more desert-like conditions.

Gerardo told us that in nearby Las Cuevas (the caves) 7000 year old bones were found in caves at an altitude of 11,250 feet. We stopped for lunch in San Antonio de los Cobres (Copper) at 12,333 feet. Here bones have been also been found dating back over 3500 years.

First a view of town prior to entering

then the welcome cirlce.

It was Sunday; mass was in session. We ate the best empanadas either of us had ever tasted cooked on the street beside the church.

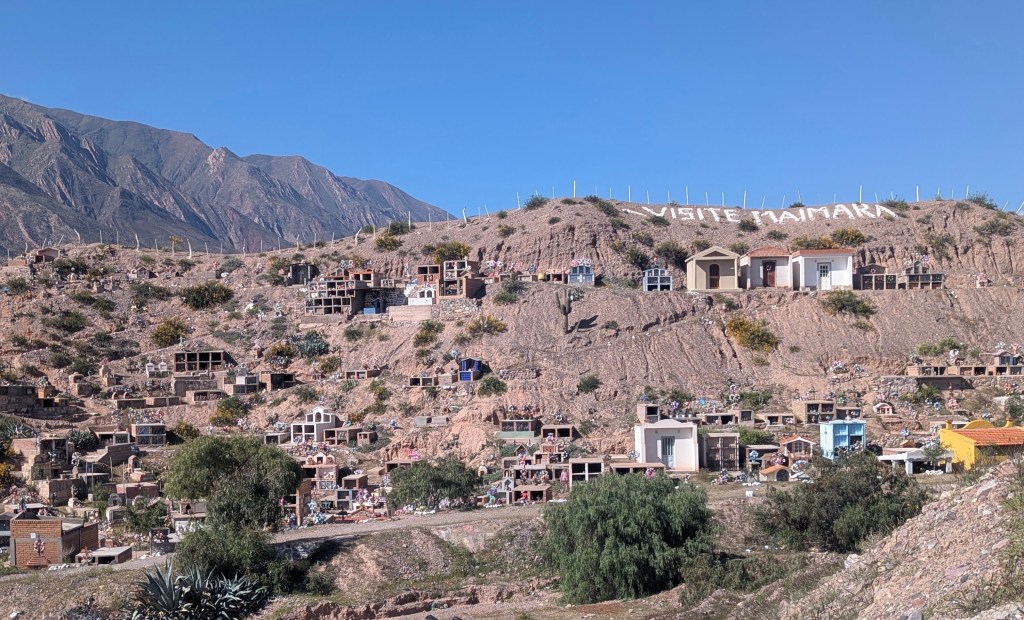

We noted the cemetery high up on the hill, closer to the sun. We also noted the water tanks on the houses.

After lunch as we passed through the desert, we saw many herds of llamas.

We just had to stop for this baby breast feeding.

Unlike llamas, which are raised as livestock, it is illegal to contain a vicuña. Vicuñas are the national symbol of freedom because they would die in captivity. They become stressed and refuse to eat or mate. They are wild and protected; no hunting allowed. Once a year they can be herded and only 20% of their wool sheared, any more would kill them.

We were able to get a little closer to the skittish vicuñas where they drank by a pair of watering holes called Los Ojos del la Mer (The Eyes of the Sea).

Eric sent up the drone for a pic of the water, but it scared the vicuñas away.

We also passed herds of donkeys, work animals for the locals.

In the afternoon we crossed from Salta Province into Jujuy Province. We stopped for a bathroom break in the tiny town of Tres Morros (Three Hills), population: 10 families, 4 here in town, the rest scattered. Electricity was introduced 2 years ago.

with its tiny chapel

and also an Incan-influenced hilltop cemetery.

As we drove we could see a distant glacier.

By late afternoon we reached Salinas Grandes, the salt flats. Seven million years ago a lake rose up from the middle of the earth. We no fresh water source, it evaporated and left behind flats of salt. Lithium is plentiful in the mud beneath the salt. We were not prepared for the expanse of salt we found there. It looks like snow and ice but is all salt.

We entered the park and paid the fee at the salt hut made from bricks of salt.

Around the entrance were statues all carved from salt.

There was a shrine to Pumamama.

We then entered the field of salt flats.

The salt extraction is performed by cutting long columns out from the top layers of salt. The salt is 3-4.5 feet thick with water beneath.

The over 2700 acre park we were visiting is owned and operated by locals who are determined to maintain their heritage and the natural beauty of the area.

Across the street lithium is being extracted on a large scale from beneath the salt flats.

We visited the artisanal stalls

Each carried numerous souvenirs made from salt.

But even more fascinating was an up close look at the bricks cut from the salt flats.

Back in the truck we headed over the highest point we were to traverse: Abra de Potrerillos at 13681 feet.

The view was great with the glaciers in the background.

But even more impressive was a look at the road we were about to travel down: the famous Lipan slope that is less than 12.5 miles in length will lead us to descend about 6000 feet until we reach Purmamarca (7546 feet).

We reached Purmamarca (Virgin Lands) in the early evening and checked into Hosteria del Amauta.

We had to walk through an outdoor courtyard

and through the breakfast room

and up a flight of stairs to reach our room.

We wasted little time before heading out in the remnants of the day to explore the town square with its daily market.

In one of the local shops we discovered charangos, a 5 string instrument in the lute family. The ones here sell for upwards of $400.

Another popular instrument for local folk music is the flute, which is different to the single rod to which we are accustomed.

In the center of the town square is a statue of a famous local guitarist. I am guessing from his name that the slope which we descended earlier in the day was named for him.

Just beyond the square is the church.

Around the church stand several very old black carob trees. This one is 300 years old.

And this one is 700 years old. It is so large I could not get it all into one shot.

Behind the church is a statue of Cacique Viltipoco who was an indigenous leader of the Omaguaca people and led the resistance to the Spanish invasion in the late 16th century.

The town of Purmamarca sits at the foot of the 7 Colors Hills. More on that later, but a hint of it can be seen in the mountain behind the shops.

Scattered throughout the town are some really gorgeous private homes.

Finally it was time for dinner, which we ate in the restaurant Los Morteros, right next to our hosteria.

The morning found us back on the road headed through the Valle de Quebrada de Humahuaca up the historical silver trade route to, now, Bolivia. We asked Gerardo about the charangos and he introduced us to the music of Ricardo Vilca (1953-2007), one of the most famous charangistas, who was born in Humahuacha, our destination for the day. The instrumentals played while we drove past high altitude vineyards surrounded by cacti, not a sight one sees often, and amazing landscapes.

We stopped at a particularly picturesque cemetery.

We were scheduled to stop at the partially rebuilt remains of the Pucará de Tilcara, a pre-Hispanic hilltop fortification. But it was closed because the staff, who are part of the university system, are on strike to increase their $400/month salary for a 48 hour work week. (No, I am not missing a zero. Doing the math, that comes to about $2 and hour for a university position!) Instead we stopped in the town of Tilcara and took a picture of the ruins from a distance. The pyramid in the center was built in 1935 as a monument to the archaeologists themselves and as a marker honoring the indigenous cultures of the region.

The colorful hillsides beyond the town are called Paleta del Pintor (Painter’s Pallet), created by a natural dam collapse 12-15,000 years ago.

We walked around the town of Tilcara, population 1500.

We drove past a hole in the mountainside created when it was struck by a meteor, which has since been removed to Buenos Aires for study.

We passed the Tropic of Capricorn, an imaginary line of latitude at approximately 23.5° south of the Equator marking the southernmost point at which the sun’s rays fall directly overhead at its zenith, occurring on the December solstice. In Argentina, the line cuts across the mountainous, semi-arid valley of the Quebrada de Humahuaca, where it is marked by a monolith in the town of Huacalera.

On the roadside locals were selling ceramics.

and little figurines made of a local beautiful blue stone.

We passed a mountain resembling the skirt of a girl.

There were several areas along the way of Inca ruins.

From there another view of the Girl’s Skirt Mountain.

We passed some of the highest vineyards in the world at over 9000 feet. Some of the wines are stored in barrels in old miners’ caves. We passed a guacito shrine.

We stopped in Uquia to visit the 17th century chapel. Unfortunately photos were not allowed inside. There we found the oldest altarpiece in the region, worked in laminated gold, being one of two existing in Argentina, decorated with oil paintings of the Cuzco school. The 9 oils (there were supposed to be 12, but they were never completed) are interesting because they depict angels dressed in Spanish clothes carrying weapons.

Humahuaca, with a population of around 15,000, is the largest in the area. It gives its name to the ravine. With cobblestone streets and iron streetlights on the corners, it is also the highest point of today’s tour at 9649 feet above sea level. We were first greeted by murals, for which the city is known.

We stopped at the town hall,

the church,

and the main square.

A school pep rally marched by, complete with band and singing.

We saw more murals

We lunched at Pachamanka Restaurant.

After lunch we visited The Monument to the Heroes of Independence.

The monument represents progress, looking forward after Conquering the Spanish.

And we saw yet more murals.

Lucamar, the Humahuaca Devil, is a half human half primate character encorporated into local mythology to scare any potential thieves along the trade route. Now he has become a beloved cultural figure, not an evil entity. He’s a symbol of celebration and tradition and plays a part in Carnival, which happened to be ongoing while we were visiting. There were 2 murals depicting him.

We drove back to Purmamarca along the same route. The afternoon sun was more conducive to capturing the beauty of the colors in the hills.

Back in Purmamarca we dined to the celebratory sounds of carnival. In the morning, before hitting the road, we hiked the trail of the Cerro de los Siete Colores (The Hill of Seven Colors), which began just behind our hosteria. The lighting was not perfect, but the colors magnificent nonetheless.

We climbed to the Mirador del Porito.

The seven colors are, of course, due to the many minerals which enrich the soil and rocks of these hills.

We could not resist posing with the llamas to send a pic home to the grandkids.

We continued back into town

There we found some murals, but nothing as extensive as those we had seen in Hamahuaca.

After lunch we headed back to Salta via a different route than that by which we had come. It was less than 20 miles from the desert to the the high altitude jungle, called Nuboselva. The beginning of the jungle is called Parsons, named for all the priests and monks who settled in the area. The area now is full of sugar and tobacco plantations.

The Incas came to the jungle for medicinal herbs. Last autumn there was a fire here, which Gerardo said was the first in his lifetime. (about 60 years.) We went over the Abra Santa Lara (Saint Lara Overpass).

The jungle is neither a park nor a preserve, but it is still considered a protected land. There were horses grazing along the way.

We drove through San Salvador de Jujuy, the capital city and the largest with a population of over 28,000. We did not stop. Back in Salta that evening we returned to peña La Vieja Estacion to enjoy more folk music and dancing.

The next day we were to have flown to Iguazu Falls, but the airline had cancelled the flight. We were blessed with a free day in Salta, a city we had come to love. We wanted to go to the summit of Cerro San Bernardo, so we headed for the gondola. Along the way we passed the public hospital.

We rode the Teleférico San Bernardo cable car to the top.

From the car we saw the statue of Christ.

We reached the top.

From there we had a view of Salta.

We meandered through the park.

Enjoyed the falls.

It wouldn’t be Argentina were there not someone with a mug of matte.

We enjoyed the afternoon amongst the flowers.

We rode the gondola back to the base and found yet another park.

Returning to our hotel we passed an appealing apartment building.

On our final morning, while enjoying our last breakfast in Hotel del Vino, we noted copies of the oil paintings of the Cuzco school from the Uquia Chapel.

I guess having previously not know what they were, we hadn’t really noticed.